(Publisher’s Note: This article was published on the blog, Moundsville.org, and has been shared with LEDE News by the author.)

The first forward pass in the history of professional football was recorded in 1906 by a Massillon, OH, Tigers quarterback named George “Peggy” Parratt against a “combined Benwood-Moundsville team,” according to the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s official account.

New research has cast doubt on that claim, but before we go there, let’s answer this question: What exactly is Moundsville — yes that Moundsville, the West Virginia river town that is the subject of our documentary on PBS – doing in a history of professional football?

The answer lies in the invention of the game itself, which evolved from an Ivy League incarnation of rugby to Midwestern factory town muddy gladiatorial combat to America’s favorite Sunday pastime. The history of football, which after its creation became especially popular up and down the Ohio River, is also a tale of culture and class, of the connections between towns and cities, and of the growth of leisure in industrial America.

The first recorded game was Princeton v. Rutgers in 1869 (Rutgers won, 6-4). The sport travelled west with the burgeoning of factories after the Industrial Revolution. The first professional teams were, appropriately, formed in Pittsburgh in the 1890s, Gregg Ficery, a researcher who is soon to publish a book called Gridiron Legacy about those early days, told me. His great-grandfather Bob Shiring was a star of some of those early teams.

Teams hired working-class toughs, as well as flashy Ivy Leaguers. One of the first pro football squads represented what’s now the Carnegie Library in Homestead, PA. They paid cash, a few hundred bucks a season at the most. The best players hopped trains from town to town, playing for the highest bidder. Teams played in loose affiliations that did not resemble today’s leagues. The National Football League wouldn’t be created until 1920.

This version of the game was far more dangerous than today’s. In a classic 2012 Sports Illustrated account, Richard Hoffer described a bloody battle.

In 1905, 18 men died playing football and hundreds more were seriously injured, some of them paralyzed at the point of a flying wedge, a medieval formation that promised a certain kind of gladiatorial excitement. There was a growing outcry, especially in the bigger cities and certain universities, and even calls for the sport’s abolition. President Theodore Roosevelt, supposedly horrified by a picture of a bloodied Tiny Maxwell (no such picture has ever been reproduced), threatened to ban the game by presidential order. The rules were changed in January 1906 to open up the game with the forward pass, but football remained as coarse and violent as ever.

Midwestern industrial America, a smoky land of striving immigrants doing hard, dangerous physical labor, fell in love. By 1906, wrote Hoffer, football “had grown into a fairly important pastime, especially in the hinterlands of Ohio and Pennsylvania. The bigger cities, with grander ideas of themselves, clung to the more refined entertainments, such as opera and baseball, leaving football to the blue-collar towns, where few felt the need to apologize for their tastes in recreation.”

Two Ohio super-teams formed: the Canton Bulldogs and the Massillon Tigers. They spent fortunes to buy up all the best players “for the glory of winning the Ohio state title,” Ficery told me. “There were probably hundreds of teams all over the country, and skill-wise, they couldn’t compete. It would have been like a high school team playing the Chiefs.”

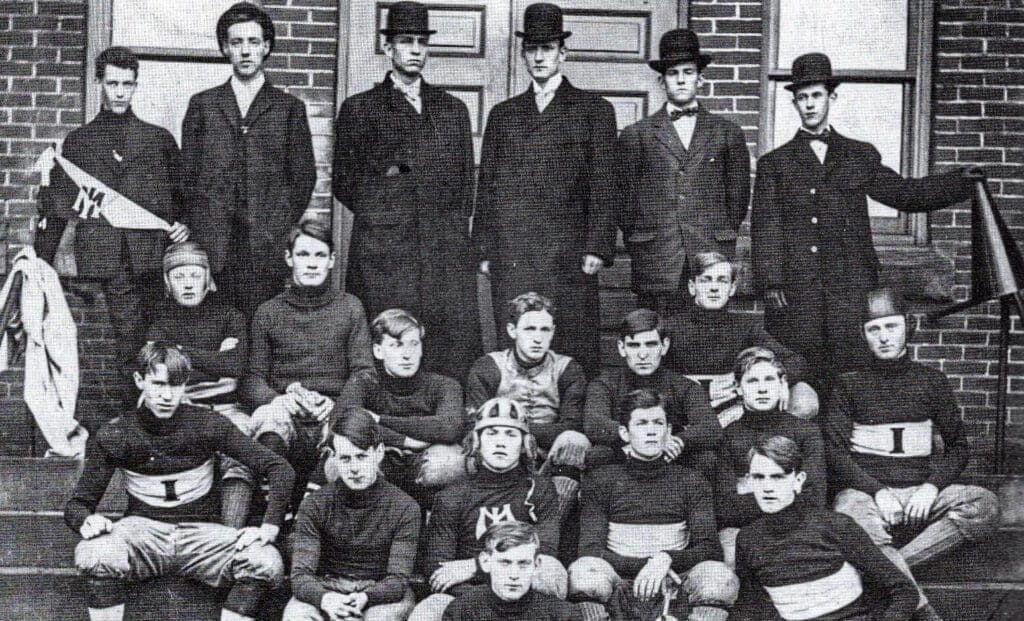

One of those hundreds of teams represented Moundsville. The club was called the Independents, according to town historian Gary Rider, who sent me this picture.

“They don’t really look much like a football team,” Rider told me. “I hope they had fun and didn’t get hurt, but I doubt it if they were playing Massillon.”

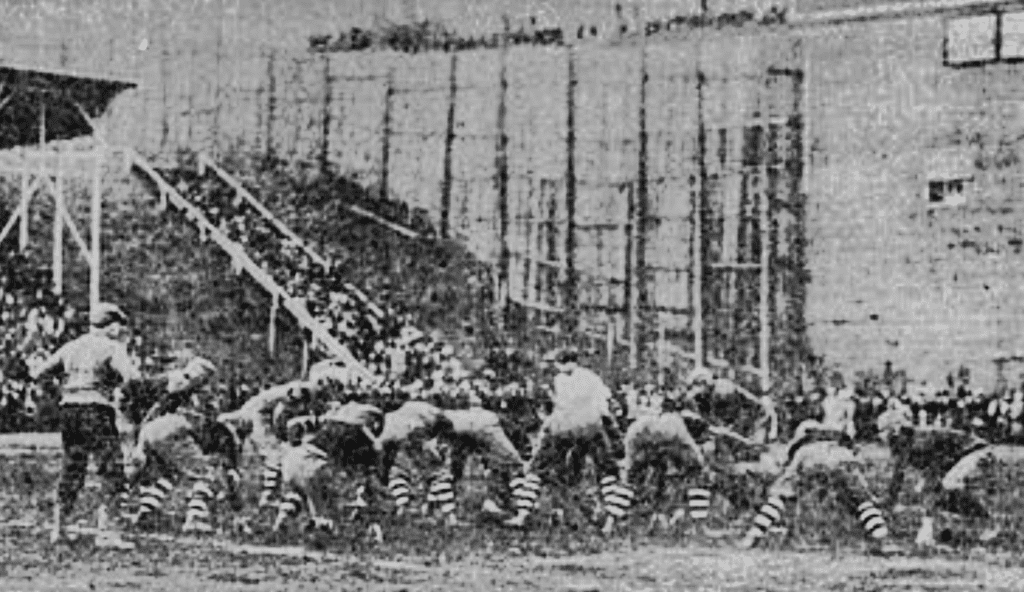

In November 1906, Massillon and Canton played twice in a series Hoffer baptized football’s first Super Bowl. In November 1906, Massillon and Canton played twice in a series Hoffer baptized football’s first Super Bowl. They split the first two games, leading some to suspect a prearranged third game that never happened.

Instead, headlines of an alleged gambling scandal forced the Bulldogs to plead with the Tigers to play an exhibition game, which few fans chose to attend, to raise money for their players’ train fares home. The incident derailed pro football’s development for nearly a decade just as it was taking off.

In the months before, however, Canton and Massillon’s seasons included games against a mix of collegiate, amateur, and pro teams in their vicinity– all the way to Moundsville.

In late October, Massillon beat Moundsville-Benwood 60-0 , according to a “Gridiron Gossip” item in the Mansfeld, OH, News-Journal.

Around that time, organizers had changed the rules to allow forward passes to make the game safer, and teams were starting to use the tactic. Here’s the full account from the Pro Football Hall of Fame website:

“The first authenticated pass completion in a pro game came on October 27, when George (Peggy) Parratt of Massillon threw a completion to Dan (Bullet) Riley in a victory over a combined Benwood-Moundsville team.” (That’s not a typo. The first QB to throw a forward pass was a man named Peggy.)

According to football researcher Bob Carroll, “unfortunately for the stuff of legends, the toss gained only a few yards and played no part in the game’s outcome.” (Thanks to MLB historian John Thorn for that tidbit.)

However, now there is a challenge to Moundsville’s place in the history books.

Ficery, the football researcher, has dug up evidence that the first pass was thrown earlier that month against a standalone Benwood squad.

“A recently discovered article in the Massillon Morning Gleaner, chronicling a game between the Massillon Tigers and the Benwood (West Virginia) team, references forward passes by Tigers quarterback Charley Moran on October 13, 1906,” Ficery wrote in a recent Pro Football Researchers Association newsletter entry. Moundsville was likely combined with Benwood to give the team a better chance, he noted.

“The history of the forward pass is tricky,” Jon Kendle, Vice President of Archives, Education&Football Information at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, OH, wrote me in an email. “When it comes to early history like this, we try to stay away from firsts or only. Opting for first known instead. But yes, based on Gregg’s research, the history should be updated.”

As of this writing, however, Moundsville is still included in pro football’s official history.