(Publisher’s Note: This is a historical account composed by local educator and historian Pete Chacalos. Pete is a former Ohio County Board of Education member and a retired science teacher who spent more than three decades in classrooms.)

Fort Sumter fell on April 14, 1861.

The next day, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 75,000 state militiamen to put down the rebellion. Thousands in the Midwest immediately volunteered. In Ohio, Governor William Dennison lobbied George McClellan to assume command of Ohio’s militia forces. McClellan accepted on April 23, 1861. Governor Dennison sent McClellan to Columbus to evaluate the state of Ohio’s arsenal. McClellan, accompanied by Jacob Cox, found crates of rusted muskets, mildewed harnesses, and some inoperable cannons. This did not deter him from creating an exceptional force of volunteers.

McClellan’s efforts were noticed in Washington.[1]

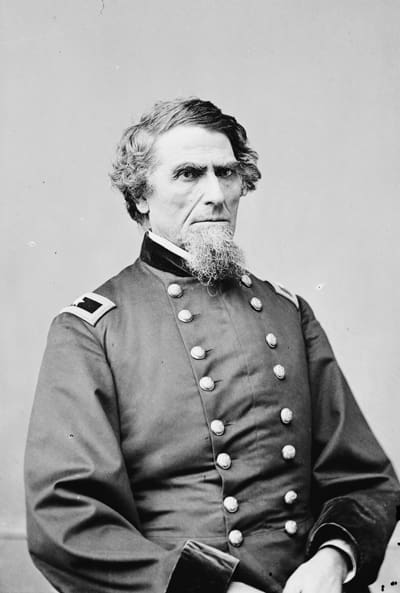

The buildup of forces in the Midwest following Sumter’s fall was so swift it outpaced the existing structure. This lack of organization was evident when, on May 3, 1861, the Union War Department issued General Order Number 14 to consolidate regiments from Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois into the Department of the Ohio. Later, regiments from Missouri would be added. On this day, McClellan rejoined the Army, was promoted to Major General, and assigned to command the Department of the Ohio, headquartered in Cincinnati.

Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee had cast his lot with the Confederacy. He was appointed to command military forces in Virginia. On May 4, 1861, he sent Colonel George Porterfield to Grafton to organize troops that were being raised there. Grafton was a key strategic point in western Virginia, as it was at the junction of the Parkersburg-Grafton Railroad and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Lee, however, did not foresee the amount of resentment that the people west of the Alleghenies had for the so-called elitist populace of the Tidewater region. The few men who rallied to the Confederate cause had little or no training. Ammunition was lacking, and some of the few companies raised in nearby towns didn’t have weapons. [2]

As Porterfield would later say in his report:

“This force is not only deficient in drill but ignorant, both officers and men, of the most ordinary duties of the soldier. With efficient drill officers, they might be made effective, but I have to complain that the field officers sent to command these men are of no assistance to me and are, for the most part, as ignorant of their duties as the company officers, and they as ignorant as the men.”[3]

Porterfield received intelligence that Federal troops were approaching from Wheeling. Realizing that he could not hold Grafton (a pro-Union town) with the 800 troops at his disposal, Porterfield withdrew 25 miles south to Philippi (a secessionist town). As he retreated, Porterfield burned a few bridges to slow any pursuit from the federals.[4]

On Sunday, May 26, General McClelland received word that bridges on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in western Virginia had been burned the previous night. The B&O was a vital link between Washington and the Midwest. It provided an easy path through the Appalachian Mountains but passed through Confederate “territory” in three places. McClellan launched an invasion into Virginia to protect against the B&O and the loyal citizens in western Virginia. [5]

He ordered the 1st Virginia, the 9th Indiana, the 16th Ohio, and some companies from the 2nd Virginia to advance from Wheeling towards Fairmont and the 14th and 18th Ohio to advance from Parkersburg towards Grafton. Early on May 27, the 1st Virginia, commanded by Colonel Benjamin Franklin Kelley, left Camp Carlile on Wheeling Island and marched across the Suspension Bridge to the B&O depot.

On May 29, the train picked up the regiments of the 16th Ohio at Camp Buffalo on the way to Fairmont. As Kelley moved east on one branch of the B&O Railroad, he was under orders to take no risks. If confronted by a force superior in manpower or firepower, Kelley was to observe and send for support. Kelley’s main objective was to protect the railroad and bridges on the way to Fairmont. [6]

The 14th and 18th Ohio, based in Marietta, crossed the Ohio River, marched to Parkersburg, and boarded a train heading east towards Grafton. In Indianapolis, Brigadier General Thomas A. Morris received orders to prepare for a move, with the 6th and 7th Indiana, to Grafton. General Morris arrived at Grafton on the evening of June 1. He met with Colonel Kelley, who had organized an expedition against the Confederates at Philippi that night. After conferring with Kelley, Morris determined that the attack would occur the following night. [7]

At 9 a.m. on June 2, four regiments, organized into two divisions, left Grafton and headed for Philippi. One division (the left column) of 1,600 troops, under the command of Colonel Kelley, consisted of six companies of Kelley’s First Virginia, six companies of Colonel Irvine’s Sixteenth Ohio, and nine companies of Colonel Milroy’s Ninth Indiana. The left proceeded east on the B&O Railroad for six miles. This was intended to give the illusion of an advance on Harper’s Ferry. The men then disembarked and marched (on a little traveled road) southeast the remaining twenty-five miles to Philippi. The march was regulated, so the column arrived at its designated spot, behind the town (south) as close to 4 a.m. as possible.

Colonel Ebenezer Dumont (commanding the right column) proceeded by rail to Webster with a force of 1,400, including the eight companies of his Seventh Indiana regiment. At Webster, Dumont was joined by Colonel Steedman and five companies of the Fourteenth Ohio, along with two field pieces, and by Colonel Crittenden, with six companies of his regiment, the Sixth Indiana. From Webster, the right column marched to Philippi, so it arrived in front of the town (north) at 4 a.m. The objective of Dumont’s column was to divert attention until the attack made by Colonel Kelley and to aid him if resistance was offered.

Once the two columns joined, the force was to be under the command of Colonel Kelley.[8]

Both columns advanced on Philippi through torrential rains. Porterfield was aware of the approaching Federals. [9] After conferring with his officers that evening, Porterfield decided the only hope of avoiding capture was a retreat (at daybreak) to Beverly. Most likely due to the storm and a lack of training, the Confederates had not set pickets that night to warn of any approach by the enemy. [10]

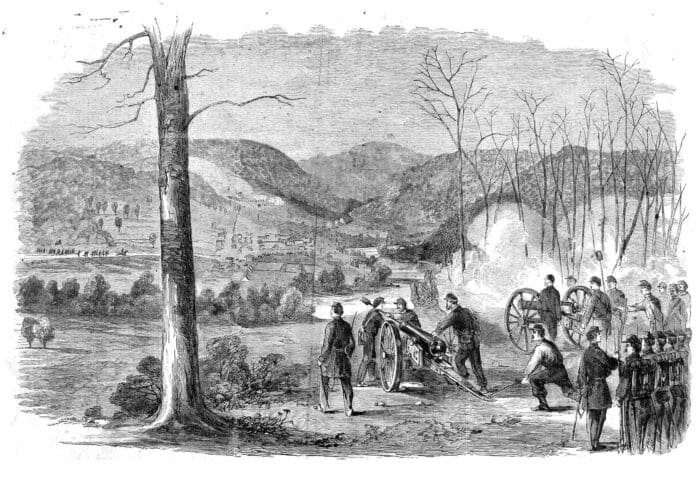

Colonel Dumont’s column arrived on a ridge east of the town known as Talbot Hill. An artillery battery was placed here to support the column as it crossed the covered bridge into town. Dumont was to wait for a signal (a single shot) from Colonel Kelley indicating his troops were in place before commencing the bombardment. At this point, Kelley should have been circling around town and approaching from the south. The plans, however, had already gone awry. Kelly’s column had taken a wrong fork in the road and ended up on the same side of town as Colonel Dumont’s men. As Kelley’s column approached Philippi, it passed by the home of Matilda Humphreys. Mrs. Humphreys sent her son to Philippi to warn of the approaching Federals.

He was immediately captured. Mrs. Humphreys fired a single shot from a pistol at the men capturing her son. Hearing the shot, Dumont ordered the battery to commence firing to support his advancing troops.[11]

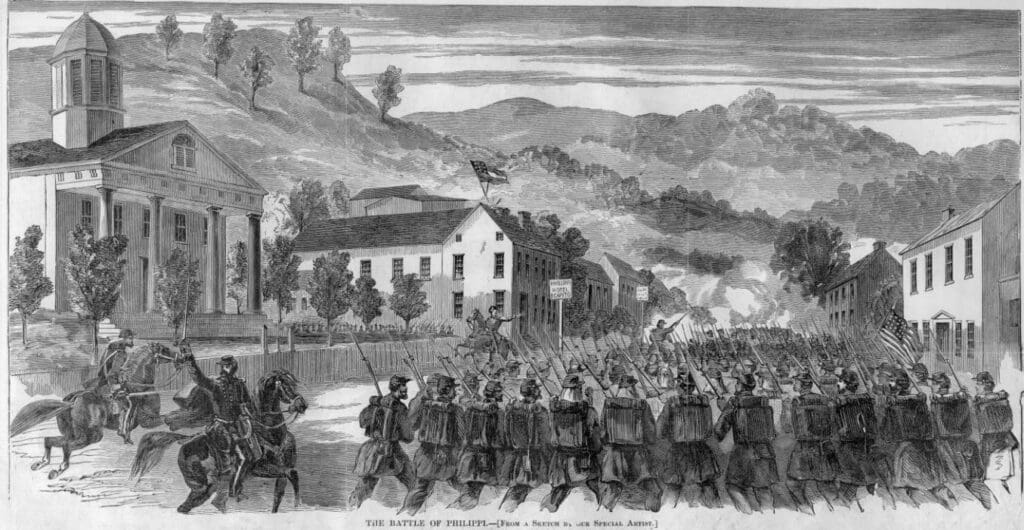

Colonel Porterfield ordered two companies to prevent the Federals from crossing the covered bridge. They put up a light resistance, but it was too late. Colonel Frank W. Lander, seeing this resistance, made a mad dash (on horseback) down the hill through heavy underbrush to rally the men in their attempt to enter the town.[12] At the same time, Kelley was advancing into town. Upon seeing two Federal columns entering the town, the Confederate forces panicked and ran. Kelley and Lander entered the town simultaneously.

As he led his men through the town, Kelley was shot through the chest and fell from his horse. It was reported by Brigadier General Thomas A. Morris, in his report to the adjutant general’s office, that Colonel Lander personally captured the man who shot Kelley. [13] Kelley’s wound was thought to be mortal. The June 7 edition of the Richmond Enquirer reported Kelley’s death. Kelly, however, would recover and go on to command the Department of West Virginia.[14]

The Confederates withdrew southward and reached Beverly that evening. The next evening, they withdrew even further to Huttonsville. They remained there until General Richard Garnett arrived with reinforcements to relieve Colonel Porterfield. On July 4, A court of inquiry convened at the request of Porterfield. He was praised for his coolness and courage during the retreat but was censured for not taking precautionary measures beforehand.

He never held command again. [15]

There were conflicting reports on the number of casualties. Some indicated dozens killed and wounded, while others reported none killed. It can be said, however, that casualties were extremely light considering the carnage that was to come.

Had Kelly’s column not gotten lost, the Confederates, running south as fast as they could, would have likely been captured. Hence, the Battle of Philippi (more a skirmish than a battle) became known as The Philippi Races.

[1] Cincinnati Rover Guards, Ohio History Central, https://ohiohistorycentral.org/index.php?title=Cincinnati_Rover_Guards&mobileaction=toggle_view_desktop

[2] Battle of Philippi, http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-philippi

[3] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. II, No. 1, Reports of Colonel George A. Porterfield

[4] Ruth Woods Dayton, The Beginning Philippi,1861 http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh13-1.html

[5] McClellan Orders Invasion of Virginia, http://civilwardailygazette.com/mcclellan-orders-invasion-of-virginia

[6] Ibid

[7] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. II, No. 1, Reports of Brigadier General T. A. Morris

[8] Ibid

[9] Ruth Woods Dayton, The Beginning Philippi,1861 http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh13-1.html

[10] Battle of Philippi, http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-philippi

[11] Historical marker, The Battle of Philippi – Talbott’s Hill, Philippi, WV

[12] Ruth Woods Dayton, The Beginning Philippi,1861 http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh13-1.html

[13] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. II, No. 1, Reports of Brigadier General T. A. Morris

[14] Battle of Philippi, Richmond Enquirer, June 7, 1861

[15] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. II, No. 1, Reports of Major General George B. McClellan

Quality work.

Thank you.

I look forward to more.

Comments are closed.