(Publisher’s Note: Interstate 70 is back to being taken for granted again, and that’s OK because it took three long years for employees of Swank Construction to make local motorists feel safe again while dashing through Ohio County. Now, how much did it cost? The accepted bid was for $214 million, but officials with the state Department of Transportation have yet to release the actual cost.)

re·bar

/ˈrēbär/

noun

- a steel reinforcing rod in concrete.

And rebar is expected to remain hidden, too, because it’s a good sign of stability when the steel stays unseen. That wasn’t the case, though, with the piers supporting the 26 bridges along Interstate 70 in Ohio County.

The federal highway was extended through the Northern Panhandle in the 1950s, and the connection to the west was completed when the Wheeling Tunnel opened in December 1966. Interstate 70 stretches from Baltimore, Md., to Cove Fort, Utah. The freeway crosses through 10 states and cities like Denver, Kansas City, Indianapolis, Columbus, and Wheeling, and the 14.5 miles in West Virginia is the shortest stretch in any of the states.

And about half of that distance of roadway was a disaster before Gov. Jim Justice included the Wheeling work in his “Roads to Prosperity” campaign, and the state awarded Swank Construction the $214 million contract to replace or refurbish 26 bridges and ramps. Despite the coronavirus pandemic, the company made good on all project deadlines, and the Wheeling community was given back its “Main Street.”

The Governor’s Office announced on January 27 the final cost of the I-70 project was $221,034,932.55.

“Everyone said that this would be impossible, and it was going to take forever, and the traffic was going to be crazy, and everything under the sun,” Gov. Justice said in a press release. “But lots and lots of people pulled the rope, did they not? Whether it was our great Jimmy Wristen, the Department of Transportation, Randy Damron, all the contractors, all the people that made this all happen, all the great city people, the workers, and all of our officials, we’re so good in this state when we unleash us.”

A Sight Seldom Seen

There was a plywood plank bolted to the belly of Interstate 70.

That was the prescribed fix after a pothole progressed into a hole through the westbound span.

“I don’t think anyone knew that’s how (the WVDOH) fixed issues like that until that photo was taken and published,” said W.Va. Del. Erikka Storch (R-4). “It makes sense when you think about it, but the way it looks is what shocked people. I know I had never seen anything like that before, but it was an example of just how bad the interstate was.

“There was a lot of talk in Charleston about the project before it actually took place, but then these photos started showing up on social media and that pushed it forward for sure,” the lawmaker explained. “They said there wasn’t any danger that a bridge was going to collapse, but that’s not how it appeared. It looked like people were in danger.”

State Secretary of Transportation Jimmy Wriston described the 26-bridge project as “monstrous,” but no one told anybody what the massive makeover would look like.

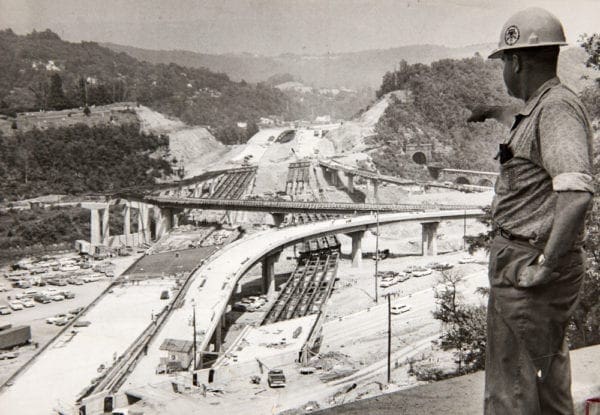

Only because of what veteran journalist Al Molnar did do we have an idea how the bridges’ skeletons would appear. Molnar, who passed at 87 years old in January 2016, was a newspaperman for the local Wheeling papers, and it was he who walked and hiked and climbed his way to the best vantage points of the construction of I-70 near Wheeling Tunnel.

Most of the interstate’s spans needed repaired and redocked, but the “Fulton bridges” were in need of head-to-toe replacement, and that meant for detour routes along U.S. 40, or National Road through Wheeling.

“And everyone, including me, thought it was going to be a nightmare,” Storch recalled. “But it wasn’t that bad because everyone was staying home because of Covid. Everyone was working from home or quarantining, and there just wasn’t that much traffic. I’m sure that let those workers just move right along.

“I know everyone is relieved now that it’s over and reopened, but that work was way overdue. It shouldn’t have been allowed to get that bad,” said the lawmaker. “But I-70 should be good for a while.”