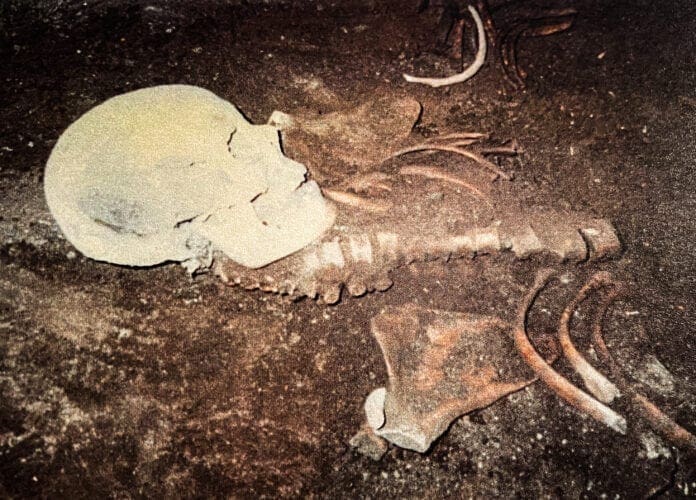

She was found in a fetal position, and the remains of what the investigators and scientists figured were of her newborn child were close by.

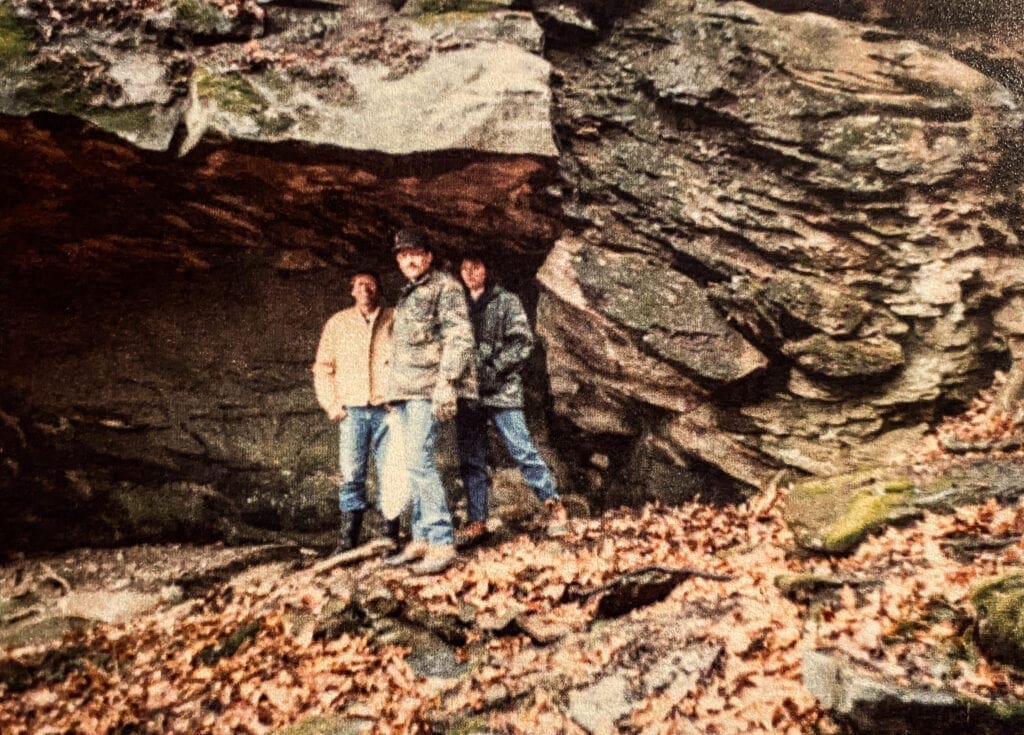

What was discovered by the property owners on March 17, 1991, were skeletons, and many of the bones had been fractured by rocks that fell from the rock overhang where the remains were uncovered. A pair of McCardle family members, according to the reports on file at the Marshall County Sheriff’s Office, were walking their property and decided to take shelter under the same overhang, and that’s where this mystery begins.

Since this took place before the Internet was readily available to the public, it was an encyclopedia volume on human bones the McCardles reviewed before making the morning call to the Marshall County Sheriff’s Office. Deputy Investigator Dan Livingston responded, driving the 30 minutes it took to arrive at the Sally’s Backbone Road address, and then trekking more than an hour through a rugged stretch of woods near Lynn Camp along Fish Creek.

Fingers were pointed at the obvious, and after film photos were snapped, Livingston removed the fallen ceiling rocks and found most of the bones that make up the human body. It was immediately evident to the detective that the remains had been there for a number of years because no flesh was found, and some bones appeared gnawed by rodents.

But how long the remains were there is another piece of this puzzle.

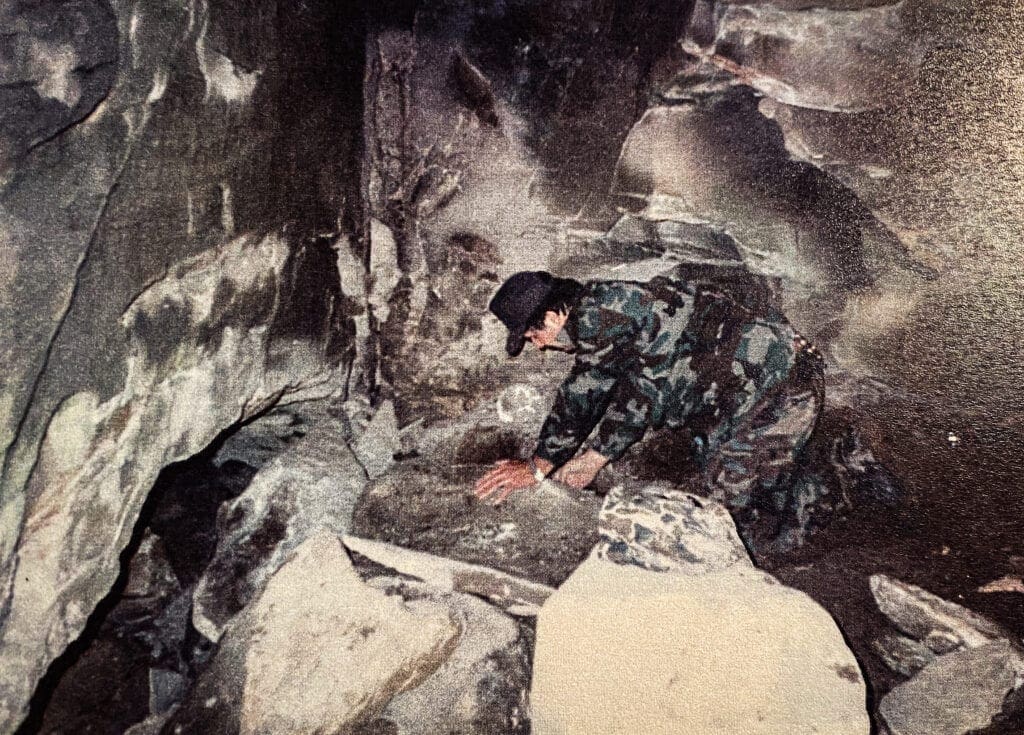

Livingston scoured the dirt with an old window screen for any possible clues like a belt buckle, a shirt button, a rivet from a pair of jeans, or the underwire of a bra in an effort to date the possible crime, but he found nothing. There were reports of missing persons on file with the sheriff’s office, but not a single one fit the timeframe this case indicated.

The deputy collected the bones, placed them in a box, and submitted the remains of “human skeletons.” He then sought the assistance of the county coroner, West Virginia’s medical examiner’s office, and a forensic anthropologist from western Pennsylvania. After countless phone calls, a number of letters, and a few reports, however, Detective Livingston still does not know who owned the bones in that box.

The Call

“Complainant called and advised that while he and his brother were taking a walk today on their land in St. Joe, they found what they believe to be human bones.”

And that is exactly what Livingston encountered, but while the “where” question was answered, the who, what, when, and why ones were not.

“The location of the rockshelter is out near Fish Creek, and you had to go in on the top. It was on the family’s land, and one of the McCardles had to take me down there so I could see what they had reported. I’ve known the McCardle family for a lot of years, and they are good people, and that’s why they called in the report,” Livingston remembered. “It took us a good while to get there; I know that. It really wasn’t a cave, though, because it is more like a rock overhang where the remains were discovered.

“Before I went up there, I went home and grabbed an old screen, and then I used it to see what could have been in the dirt near the remains. I remember that I didn’t find any buttons or metal objects from clothing, and I found that to be odd at the time. We all know that Marshall County has a lot of history with Native American tribes, so that was a theory, too. That the remains were from a female who went to that overhang for some reason and perished while there.”

Someone was dead in a conspicuous place, and there appeared to be a baby involved. Did the female and fetus die because of the collapsing ceiling or for other reasons?

“It was one of those deals where people didn’t know who or what,” Livingston recalled. “There was a report that there was someone in a cave, so I went out there by myself and tried to get everything I could. I collected the remains after searching the area, and those remains went to the medical examiner.

“It also appeared as if there was a fire at one time under there, and the ceiling was darkened by it,” he said. “And there were large rocks that came down from the top, and they were on the remains of the female that was discovered there. I believe those guys were out there hunting, and that’s when they went under that overhang and found what they found.”

This One Day, At Lynn Camp

Moundsville is the home of the Grave Creek Mound that rests across Jefferson Avenue from the former W.Va. Penitentiary, and the burial mound measures 62 feet high, 240 feet in diameter, and was created by moving more than 60,000 tons of dirt. The Mound serves as the most obvious pieces of proof that the Upper Ohio Valley was inhabited by Native American tribes, but many accounts of the Revolutionary War detail the battles between them and European colonizers throughout the Northern Panhandle and East Ohio.

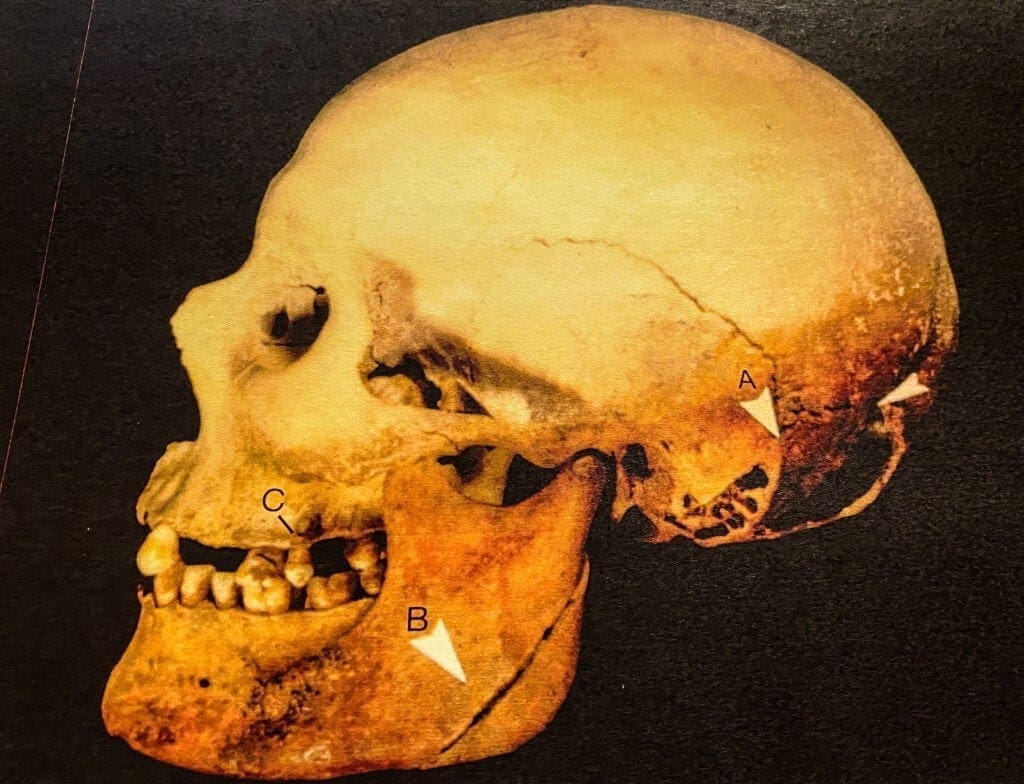

So, the theory adopted by the county coroner at the time, Dr. Norman Wood, according to Livingston, was that the remains were those of a 5-foot-5-inches tall, 35-year-old Native American; this was plausible, but Livingston still worked the case.

“There was a report about a missing woman from Wetzel County, and what I was told was that she rode a horse,” the detective explained. “The woman had gone missing several years before these remains were discovered, but when I checked, I was unable to confirm it for some reason. What I had heard was word of mouth, but Wetzel County didn’t have a report on file, and Marshall County didn’t have anything that would fit the timeframe either.

“After we didn’t know how to identify the individual, we sent them to anthropologist, and he did a diagram and a report on what he thought was there. The remains were gone for a good while, too, and the county prosecutor’s office had to send a letter to him, and that’s when we finally got the remains back,” he explained. “After that, it all went to the (Grave Creek Mound Archeological Complex), and that’s where those bones are today.”

Conflicting Reports

The anthropologist Livingston found was Dr. Dennis Dirkmaat with the Applied Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh, and two months following the discovery of the bones, the scientist mailed a three-page report that determined the remains were not prehistoric Native American.

Dirkmatt cited bone structure when determining the skeleton belonged to a Caucasian female who was 5-foot-3-inches tall and approximately 30 years old at the time of her death. He also concluded the small bones were that of a fetus or newborn baby and that the remains had been under that overhang for longer than 20 years.

He offered two hypotheses: the individual had gone to the rockshelter to give birth and complications killed both the mother and child; or that the pregnant individual went into the covering, layed down and rocks fell on her and killed her.

Three years later, however, after Dr. Dirkmaat became the director of forensic anthropology at Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pa., he filed a second report that completely contradicted his first. This time, Dirkmaat suggested the bones belonged to a prehistoric Native American who passed away from natural causes because of the nature of the fractures caused by the large rocks, the fact that no remnants from clothing were found at the scene, and because of new research in ancestry.

Livingston, who served 23 years with the Marshall County Sheriff’s Office before retiring in 2001, then received a surprising phone call.

“I was the only person from the sheriff’s office who went to the rockshelter, and I collected what I could so we could find some answers, but then, I received a phone call from the office, and I was told that I was going to get arrested because I had moved Indian remains,” he explained. “There are laws in the code that protect burial grounds or something similar, but all I did was what the coroner (Dr. Normal Wood) told me to do because we really didn’t know what we were dealing with at the time.”

The Age of Bones

Radiocarbon dating is a scientific practice that takes advantage of the natural ways atoms decay to estimate the age of skeletal remains, but according to case file #C-16-91, such tests have not been performed on the bones of the female or the fetus.

“Even today, I do believe that the remains are from Native Americans, and the female must have lived nearby,” Livingston said. “In Marshall County, you really never know what you are going to find because of all the history in this area. The overhang where they were was a perfect place for shelter because the covered area was about 15 feet wide and probably 10 feet deep.

“There’s really no way of knowing why they were there, and whether the baby was nine months or seven months old because I don’t recall there being enough bones to be able to tell how developed the fetus was,” he said. “And there was no way for me to tell if the baby had been born before the female died. There were a lot of puzzles back then, and a lot of them are still there today.”

Chief Deputy Bill Helms, the sheriff-elect in Marshall County, said the department’s detectives often review unresolved cases, and that practice will continue during his first term in office.

“That’s because, once you get a case, you work it until you come to a conclusion. Now, sometimes, that may take a longer time than you prefer, but you have to be patient and wait for the answers you need,” Helms said. “That’s our obligation, to see every case to its end, because every case deserves to be resolved.

“In this case, we do have the reports from the expert, and his most recent summary indicated that the remains are those of a Native American, he continued. “Plus, Prosecutor Rhonda Wade has communicated to this office that she sees no reason to believe that foul play was involved. That means you can consider the case closed, but if more information were to come available, we would definitely take a look at it.”

Case Closed?

In her letter dated Feb. 6, 2019, and addressed to Sheriff Kevin Cecil, Prosecutor Wade wrote, “Based upon the information that we have, I do not think there is a crime to be investigated.”

After suggesting the remains be turned over to the museum or another entity as Native American bones, she continued, “If this entity were able to conduct the radiocarbon testing, I would ask that the results be shared with us.”

Helms confirmed his plans to request an update from officials at the Grave Creek facility, and he will research the utilized methods to see if the experimentation is accurate and applicable, as well.

“Because of how technology improves on a daily basis, carbon testing is something we would consider if it’s not been performed at the museum,” Helms said. “In my opinion as the incoming sheriff, no expense should be spared when it comes to a case like this.

“There is a chance that the testing could take place in the future, and that’s why I have been looking into it,” he added. “I’m very curious about this particular case, so I would like to have those tests conducted, but I have to make sure that the methods have advanced enough, and there would be permissions that we would need, too. But it’s something I plan to look into.”

Livingston, a resident of Glen Dale who has remained interactive with the sheriff’s office, holds hope that Helms will finally find the missing pieces of the puzzle.

“It’s been a long time since I have thought about those bones of the lady and her baby, but I do remember it because of the hike it was to get to the location, and because of what those guys stumbled across,” he said. “Those men really didn’t know what they had found that morning, and now, 30 years later, we still don’t know.

“If Bill believes carbon testing would give us those answers,” he added, “I would love to see it take place.”