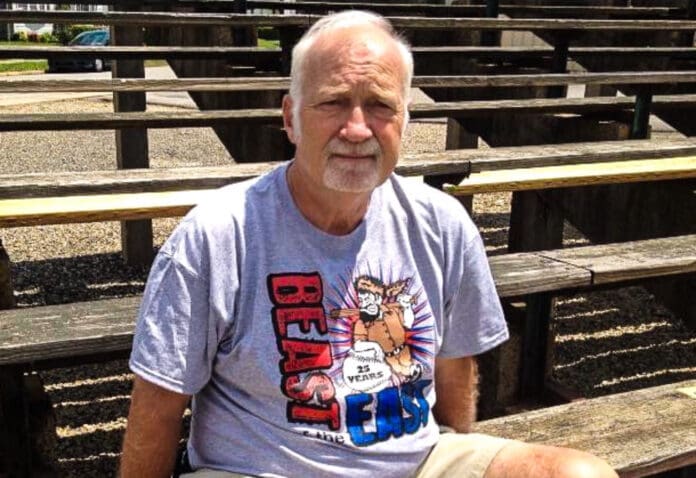

This year’s Edgar Martin ‘Beast of the East’ Baseball Tournament will be July 4-7

He was a kid growing up in “Goosetown,” a neighborhood scratched away by a highway known as “Progress” back in the ‘70s, and he played some sort of sport every second he could. He cussed, played hard, bloodied noses, swam in orange creeks, and, back in the day, that street-smart boy named Bo McConnaughy was all-everything at Wheeling Central Catholic.

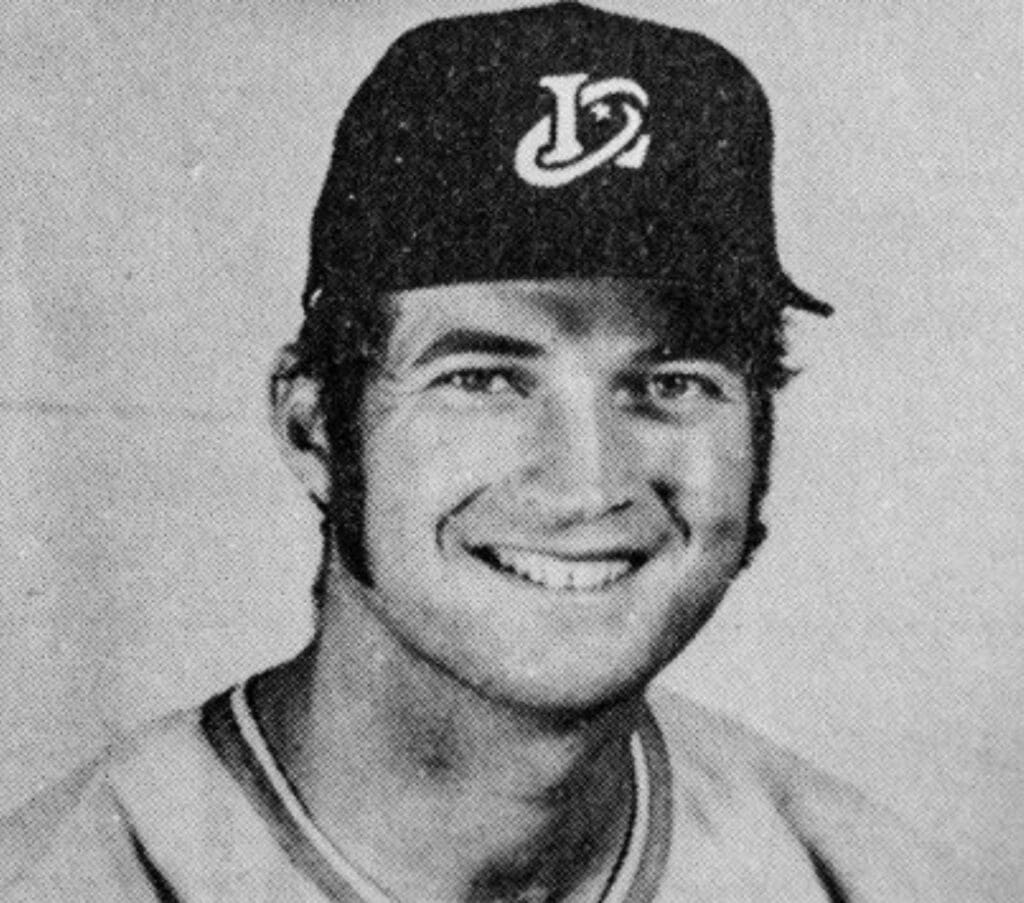

He was a state champion in basketball and baseball for the Maroon Knights and was a four-year letterman in both hoops and on the diamond at West Liberty State College. McConnaughy was the Hilltoppers’ primary playmaker on the court, but there wasn’t much in baseball he didn’t master before signing with the Baltimore Orioles in 1970.

“Baseball just makes sense to me … always has,” he said. “It sounds easy … three outs for each team every inning and the team with the most runs at the end wins. Easy, right? But it’s not, now is it?”

After just three minor-league seasons, though, pro ball’s unfeeling filter washed him out so McConnaughy came home, kept playing in a local semi-pro league, and began a 30-year coaching career at West Liberty that would lead him to more than 500 wins, five conference championships, and he was a six-time Coach of the Year, too.

Once he retired from WLU, McConnaughy returned to his high school alma mater to coach the Maroon Knights for three seasons, and he’s continued to direct the Edgar Martin “Beast of the East” Baseball Tournament since he co-founded it with B.A. Crawford in 1989. The 36th annual event is scheduled for July 4-7 and will include three age brackets for more than 30 teams.

“We had built the Beast to be a pretty big deal. We had more than 160 teams a lot of years,” he explained. “But we got hacked … the (online) server got hacked, I should say, and we didn’t know about it before it was too late and a lot of the travel teams went somewhere else.

“We started back after the pandemic and we have a lot of very good teams coming. But these days, most of these young players have only played on turf. Some have never played on a dirt and grass field,” McConnaughy said. “Can you believe that? I get the need for the artificial surfaces because of the weather, but baseball was invented on dirt and grass.”

He’s not only a local Hall of Famer, McConnaughy currently serves as the president of the Elm Grove Civics of the Ohio Valley so he can help resurrect the non-profit that has supported him for decades.

“The Civics have been a great organization that’s fallen on hard times, so I’m trying to increase memberships and have events at our building on Sycamore (Avenue) so we can do repairs that are long overdue. It’s just something I gotta do.”

Baseball and Life, Too

His West Liberty players mostly were local student-athletes from the Ohio Valley Athletic Conference, and his teams were most successful in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

McConnaughy attributes much of his success to the high school coaches and their players during an era when professional baseball scouts – and their radar guns – could be found at ballfields on both sides of the Ohio River.

“This valley was rich in players who could really play the game. The communities had their teams, and the midget leagues we had were really development leagues. And there were a lot of great ballplayers,” McConnaughy said. “Every high school team and all of the legion teams had guys who were moving on to the next level, and we’ve had a lot of guys from this area who had nice college and pro careers.

“It’s a great game and those players knew it,” he added. “That’s why they had success.”

But it always takes a team that’s working like a team, McConnaughy insisted, and it doesn’t matter if it’s baseball, the staff and volunteers with the Beast of the East,” or if he’s working with the growing membership of the Elm Grove Civics of the Ohio Valley.

“To accomplish goals as a group, you have to believe in each other, pick each other up, and don’t care who gets credit for anything,” he insisted. “There’s always some point in everything where your team has an opportunity, and a team has to do that together. For example, in baseball, you have to get runners on base, and then someone else has to come up with the big hit.

“When you win, you win, and when you lose, you lose, but if you have a true team, you’re always going to win more often. That’s because a team can talk about why they lost, and then worry about what happens next,” he said. “And I don’t care what kind of a leader you are; if the team members don’t believe what you’re trying to do with them is going to be best for them and the team, forget it.”

Talking Turkey

“Goosetown” was a blue-collar neighborhood of families where the fathers worked hard, the mothers raised the children, and the kids ran the streets, camped in the woods, and dodged the daily trains on the tracks that ran through East Wheeling’s Hempfield Tunnel.

There were bars mixed in with more than 100 homes, and also a garbage incinerator and city dump, a mechanic’s garage, a trolley and bus barn, and a ballfield with home plate tucked in the northeast corner near Wheeling Creek. Once the state of West Virginia purchased the properties to make room for W.Va. Route 2, only McColloch and Baltimore streets remained. These days. a dog park, Tunnel Green field, and an event shelter rest where Bo was raised.

McConnaughy’s father was known as “Chibe,” and when it came to everything in life, he was considered as “old school” as they came. He was a ballplayer, too, and a coach, and, according to his son, he taught his little league players the basics.

“The fundamentals are still the same no matter what terminology they use these days,” McConnaughy said. “When my dad coached, baseball is baseball, and it’s still that way and I love it more than ever. I still try to teach kids how to play it the right way like my dad did. You have to be able to catch it, throw it, and hit it, and not be afraid of it. If you can do those four things, you’ve got a shot at playing the game.

“It all takes development over the years, but people want their kids to be good right now, not later,” he said. “That’s not how it works, and you would think someone would have realized that by now.”

The same goes with coaching no matter how you go about it.

“The good thing about coaching is that everyone has a different style and a different way of doing it. Each coach has his or her own style. And if it works for you, you stay with it,” McConnaughy explained. “And it works the other way, too, because if your players don’t buy in, you’re not going to have very much success at all.

“I’m sure I had some players later in my career who believed the game had passed me by and that I didn’t know what I was talking about because they wanted to go about the game a different way. There were times when some players played, but they didn’t compete,” he said. “I was raised to play the game as hard as you could, and that’s still the way you have to play the game of baseball.”