Rich Mountain and Laurel Hill were two strategic peaks in the Allegheny Mountains. Between these peaks, the Parkersburg-Staunton turnpike, leading from the Shenandoah Valley, passed through the town of Beverly.

Here, the road forked. The left fork led to Parkersburg on the Ohio River. The right fork followed a northwest route as it passed through Philippi to Grafton. The route to Grafton offered easy access to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, leading to the Ohio River at Wheeling. Rich Mountain and Laurel Hill’s strategic importance was not lost on the Confederates or the Federals.

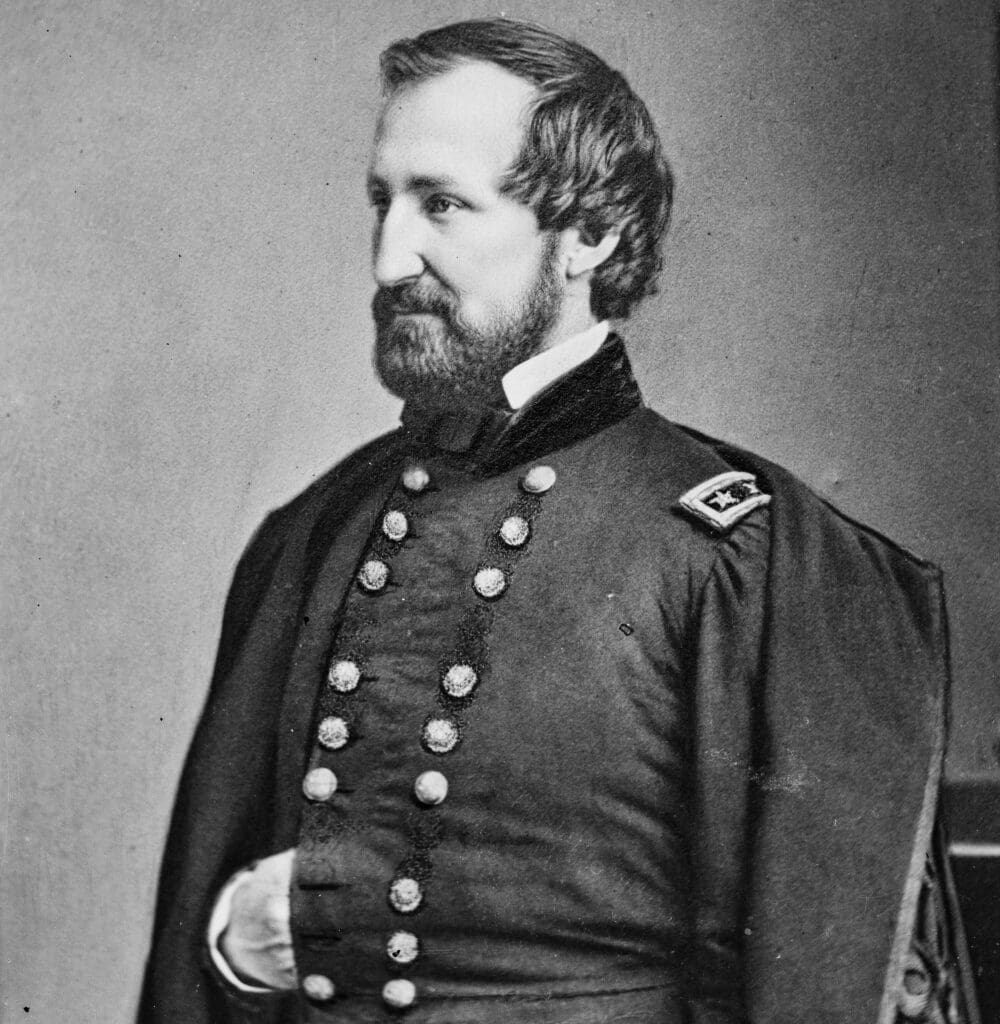

Following the Battle of Philippi, General Richard S. Garnett replaced Colonel George Porterfield as commander of Confederate forces in Northwestern Virginia. He immediately ordered the fortification of Rich Mountain and Laurel Hill to protect this vital supply route from the Federals. Garnett placed 3,500 troops at Laurel Hill, the point at which he expected an assault. The position was very well fortified and covered every approach to Laurel Hill. Garnett sent Colonel Jonathan M. Heck to fortify Rich Mountain.[1]

Colonel Heck entrenched at the western base of Rich Mountain. Breastworks on each side of the turnpike were constructed. The area in front of the breastworks was cleared in preparation for a frontal attack by the federals, affording a clear field of fire.[2] In the meantime, reinforcements arrived at Laurel Hill. Garnett sent the Twentieth Virginia, commanded by Colonel John Pegram, to reinforce Camp Garnett. Outranking Colonel Heck, Pegram assumed command at Camp Garnett. At his disposal was a force numbering 1,300 men. [3]

McClellan’s original plans called for a movement on Richmond through the Kanawha Valley. After numerous consultations, McClellan opted for a movement against Garnett. On July 9, he moved his base of operations to Roaring Creek Flats, two miles west of Camp Garrett, and sent General Thomas A. Morris to keep the Confederates occupied at Laurel Hill. [4]

For five days, from July 7 to July 11, 1861, Morris’ forces engaged in a series of minor skirmishes with Garnett’s men in and around the small town of Belington. These skirmishes, although minor, accomplished the desired effect of keeping Garnett from reinforcing Pegram at Rich Mountain. McClellan, meanwhile, was hesitant to order a frontal assault on Camp Garnett. Although there was a high probability of success, casualties would likely be high. He did not have to make that decision thanks to 21-year-old David Hart.

Hart arrived, seeking permission to visit his father’s home atop Rich Mountain. He was taken to General William S. Rosecrans for interrogation. [5]

Hart told Rosecrans of an old road, hardly used, that would lead around the left flank of the Confederates and to a dirt road a short distance from the Hart home. Rosecrans took this information, along with Hart, to General McClellan. It took some convincing, but McClelland finally agreed to Rosecrans’ plan. At dawn, the brigade, led by Colonel Frank Lander and composed of 1,900 Indiana and Ohio troops, left camp on a challenging march to the Hart farm. The soldiers made their way through brush and thickets and crossed ravines. Heavy rains fell from six that morning until eleven o’clock. The march took much longer than expected. Finally, shortly after eleven, the column reached the dirt road that led to the Hart farm. [6]

As the column began moving along the dirt road, Rosecrans was unaware of two things. When he did not hear the firing he expected, McClellan became concerned and recalled the flank attack. He sent Sergeant David Wolcott of the First Ohio Cavalry to recall the column. Confederate pickets, however, captured Wolcott, and Rosecrans did not receive the message. Colonel Pegram knew the Federals were executing a flank march. To guard against such a maneuver, Pegram placed two companies near the summit, almost two miles to his rear the previous night, to fortify the position.

When he learned of the Federal plans, he sent two more companies and an artillery piece to reinforce the summit, increasing the Confederate force to three hundred men. This left Pegram one thousand men at Camp Garnett to face General McClellan.

McClelland, with four thousand troops, could have easily overwhelmed Pegram. Assuming the troops had been defeated at Rich Mountain, McClellan ordered his line back to Roaring Creek Flats.[7]

Meanwhile, after passing the crest of the hill and about a quarter mile from the Hart farm, the Federal column began to take fire from enemy pickets. Sergeant James Taggart fell, and Captain Christopher Miller was severely wounded. The Confederate column opened fire as the Federals emerged into open ground. The Federals commenced the attack. The Confederates put up a gallant defense, but it was not enough.

Rosecrans ordered a charge down the hill toward the Hart farm as the Nineteenth Ohio provided a covering volley. After a second volley by the Nineteenth, the entire force charged, and the overpowered Confederates ran. The brief battle was over. Rosecrans did not pursue so his troops could prepare for a counterattack, which never came. [8]

Colonel Pegram was on his way to Hart Farm to check on the battle’s progress when he encountered retreating men. Pegram tried to rally the men but was unsuccessful. As he made his way to Camp Garrett, Pegram fell from his horse and suffered a minor injury. When he arrived at the camp, he consulted with his officers. With Federals at his front and rear, Pegram abandoned Camp Garnett. [9]

Because of his injuries, Pegram relinquished command to Colonel Heck, who issued orders for the retreat. It was a rainy night as the column retreated. The movement was led by Captain R.D. Lilley of the 25th Virginia and accompanied at the front by map maker of the 25th Virginia, Jedediah Hotchkiss (destined to become one of Stonewall Jackson’s chief aides). [10]

Before the retreat was completed, Pegram decided to resume command. Word was sent up the line to halt the column until Pegram came to the front. However, the men led by Captain Lilley and Hotchkiss never got the message and continued to Beverly. Lilley continued the retreat through Huttonsville to Cheat Mountain. [11]

Hearing of the defeat at Rich Mountain, Garnett knew he was in a precarious position at Laurel Hill. Leaving his tents up and fires burning, Garnett quietly slipped away and moved south on the Parkersburg- Staunton turnpike. When informed erroneously that the Federals blocked his path at Beverly, Garnett changed to a northeasterly route into the Cheat River Valley to avoid them.[12]

Meanwhile, Pegram led his column to a point three miles south of Leadville (near present-day Elkins). Pegram received some disturbing news: Garnett had retreated from Laurel Hill. Pegram’s troops were hungry, exhausted, and demoralized. He saw surrender as the only option. At midnight, he sent a message to McClellan asking for terms of surrender. Pegram’s force surrendered its arms at Beverly, and McClelland issued orders for delivering food and provisions to Pegram’s famished command, consisting of five hundred sixty men, including 33 officers. [13]

Garnett, meanwhile, was having problems. His ruse had been discovered. General Thomas A. Morris had begun a pursuit with his Indiana brigade. The poor roads slowed travel to a crawl. The Confederates chopped down trees to slow the federal advance. In addition, heavy rains turned the road into mud, slowing the advance and bogging down the wagon trains. Equipment left behind easily showed the direction of the march.

With the rains swelling the streams, the Confederates crossed the Cheat River at Kaler’s Ford. On July 13, 1863, the Federals finally caught up with the Confederates at Shaver’s Fork of the Cheat River and began their attack. From there, the conflict continued through the first and second crossings of Corrick’s Ford. The battle raged as the Seventh Indiana, led by Colonel Dumont, crossed the river and made a charge on the Confederate battery. The Southerners, low on ammunition, retreated.

Garnett, hearing the battle raging, rode back to Corrick’s Ford.[14] Upon seeing his men in retreat, he attempted to rally them. He made an inviting target on horseback, and soon, a bullet struck Garnett. He fell from his horse, becoming the first General killed in the Civil War. Under Federal guard, Garnett’s body was transferred to relatives in Baltimore, Maryland, where he was buried. He was later re-interred next to his wife in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[15]

McClellan chose not to pursue. Nine days later, on July 22, 1861, following the Union disaster at First Bull Run the previous day, McClellan was recalled to Washington, and General Rosecrans assumed command in Western Virginia.

The events in Philippi, Rich Mountain, Laurel Hill, and Corrick’s Ford were instrumental in the decision to elevate McClelland to command of the Army of the Potomac. Federal control of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Parkersburg-Staunton turnpike made it more difficult for Confederates to supply their units.

Leaders meeting for the Wheeling conventions could now breathe a bit easier knowing Western Virginia was under Union control. It would not be long before a new state was born.

[1] Jack Wills “Battle of Rich Mountain.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 28 March 2013. Web. 27 November 2017.

[2] Rich Mountain Revisited, Dallas B. Shaffer Volume 28, Number 1 (October 1966), pp. 16-34 http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh28-1.html

[3] Ibid

[4] Jack Wills “Battle of Rich Mountain.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 28 March 2013. Web. 27 November 2017.

[5] Katherine Hart Frame, David Hart and the Hart family in the American Civil War, http://www.richmountain.org/history/davhart.html

[6] Ibid

[7] Union Victory in Spite Of Itself At Rich Mountain, http://civilwardailygazette.com/union-victory-in-spite-of-itself-at-rich-mountain

[8] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. II, No. 1, Reports of Brigadier General William S. Rosecrans

[9] Rich Mountain Revisited, Dallas B. Shaffer Volume 28, Number 1 (October 1966), pp. 16-34 http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh28-1.html

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Rich Mountain Revisited, Dallas B. Shaffer Volume 28, Number 1 (October 1966), pp. 16-34 http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh28-1.html

[14] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. II, No. 1, Reports of Major General George B. McClellan

[15] Mathew W. Lively, Robert S. Garnett – First General Killed in the Civil War,