Christina Fisanick grew up in Moundsville in the 1970s and 1980s, right before the town suffered catastrophic job losses. But her childhood was a time of plenty, as she writes in her new book Pulling the Thread: Untangling Wheeling History: “When trains ran night and day throughout the Ohio Valley, the age of chemical plants and coal mines working at top speed, and the decades when the streets of Wheeling were crowded with Saturday shoppers and mill workers on their lunch breaks.”

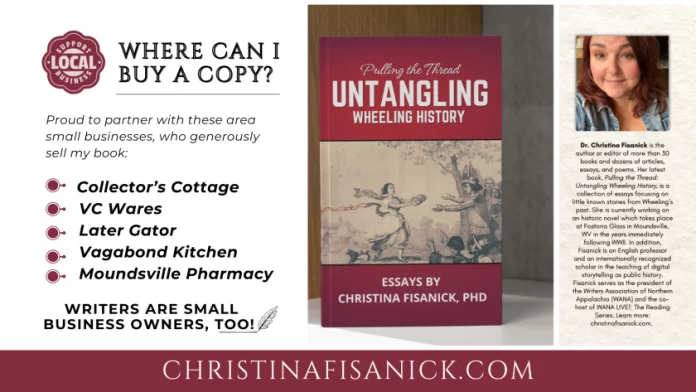

Fisanick left Moundsville to earn her doctorate in English. She then moved back to Wheeling, a much larger town of 26,000, a 20-minute drive up the Ohio River. Her book of 34 historical essays, published this year by North Meridian, a small Alabama-based press, is a rich and entertaining miscellany of local history and perspective, a love letter to a town, and a personal memoir, exactly the type of storytelling celebrated on this blog and in our PBS film Moundsville and Amanda Page’s film Peerless City, about Portsmouth, OH.

In a nation with thousands of communities in crises of employment, inequality, and meaning, America needs scholars and storytellers like Fisanick to lift up the specific narratives of their places in a way that’s authentically research, apolitical, and constructive. Not nostalgic gloss, but rather tales to build a better future on.

For a place like her current hometown, Fisanick admits: “Will Wheeling ever be what it once was? No. Can any person, place, or thing ever stay the same? But what we have here right now—in this moment—is more than most people can expect from a city the size of Wheeling in a state as economically challenged as West Virginia.”

So what is the story of Wheeling?

As Fisanick expertly recounts, humans first tramped into the Ohio River Valley around 12,000 years ago. These were Paleoindian hunter-gatherers who “lived in temporary camps of between 20 and 60 persons along the migration paths of animals they hunted for food and clothing.” The animals were extraordinary: woodland musk oxen, mastodons, barren ground caribou, wooly mammoths, giant beavers, and moose-elks. Paloindians also fished, hunted birds, and ate wild berries.

As the world heated up, the big animals went extinct, and people hunted white-tailed deer, rabbits and wild turkeys instead. They also went trading. Artefacts like copper tools and ornaments have been found from as far away as the Great Lakes and Vermont. Humans survived in bands between 20 and 100 people.

Then, over the next 10,000 years, came waves of settlements, tribes, and kingdoms. Civilizations rose and fell. Some, like the Adena people, named after the estate of the Ohio governor where remains were found, left behind dramatic burial mounds like Grave Creek Mound, Moundsville’s 69-foot conical structure.

In the centuries before Europeans invaded America, the Monongahelans lived in villages of 100 to 150 people, which they abandoned in the 1620s and 1630s, perhaps annihilated by disease and battle. They left behind striking petroglyphs on rocks and cave walls.

In the modern era, Wheeling was the birthplace of West Virginia’s morally righteous 1863 secession from Virginia’s punishing economy based on enslavement. It was also the home of Mark Twain’s cousin James Walton Clemens, who may have forged the Grave Creek Stone, an artefact allegedly recovered from inside the Grave Creek Mound.

Fisanick tells dozens of stories, some familiar and some completely unknown. During the Civil War, engineers designed one of the world’s first ambulances. In the late 19th century, cremation was invented in nearby Washington, PA. In 1970, three students organized a Black Panther Rally.

Wheeling was named after a Native American word that means “place of the head”, a reference to the town’s location near the head of Wheeling Creek. It was incorporated in 1805, early enough that there are over a dozen villages, town, townships and cities across America named after Wheeling.

What a lot of people in places like New York and Washington miss is just how wealthy a place like Wheeling could be. It was so much more than a coal mining town; rather one of America’s economic linchpins. Eleven U.S. presidents spent the night at the McClure Hotel. There is an alternate history here where Wheeling, not Pittsburgh, becomes the star of industrial America.

Hazel-Atlas Glass was one of the world’s largest glass manufacturers, employing nearly 5,000 people at its Wheeling headquarters and nearby metal plant. The Crown Stogies factory, West Virginia’s largest cigar maker, employed over 500 people. Earl Oglebay founded Oglebay Norton Company, an iron ore shipping line he sold to U.S. Steel in 1900. Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco supplied the country with chaw, and left over 20,000 Mail Pouch ads – “Treat Yourself to the Best” — on the sides of barns across America. By 1930, the population topped 60,000.

That prosperity has evaporated. Wheeling, like Moundsville, has lost many thousands of jobs. But there is grit and resilience in those hills. Fisanick quotes Ma Joad from John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath: “We’re the people that live. They can’t wipe us out. They can’t lick us. And we’ll go on forever, Pa… ’cause… we’re the people.”

Fisanick concludes: “West Virginians… we’re the people. Fellow Wheelingites… we’re the people. And every day I am proud to be one of ’em.”

John W. Miller