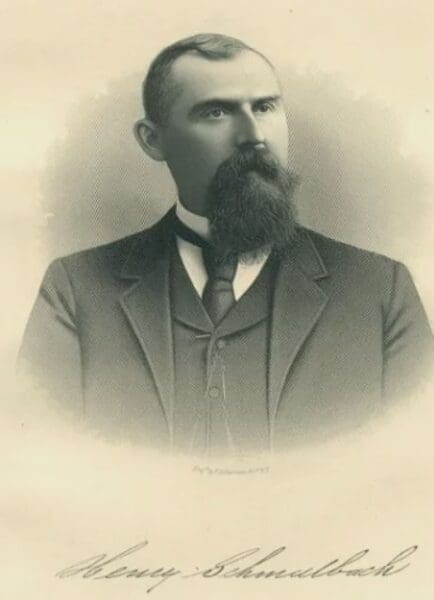

Henry Schmulbach was a leading beer brewer who became a banker in Wheeling, and eventually, the immigrant’s son established himself as one of the wealthiest individuals along the country’s East Coast.

He constructed an impressive mansion on Roney’s Point, the first dwelling in the region with air conditioning, and he owned horses and fast cars and monogrammed everything prior to passing away in 1915 at the age of 70.

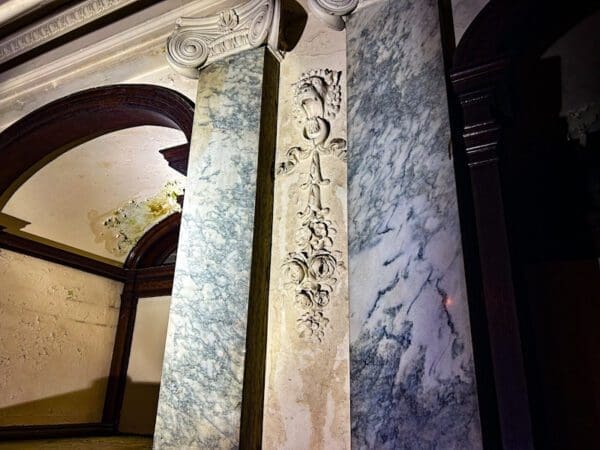

But first, he built his building. It was 12 stories tall because it had to be the tallest, and it was constructed with marble because marble was the best. The ceilings were high, each door handle was carved with his initials, and the views from the top floor displayed his dominance of the local economy. Not long after his death, though, the Schmulbach Building was purchased and transformed into the headquarters for Wheeling Steel Corporation, a new company that would assist in the development of the mysterious West.

Eventually, the steel company would merge with a Pittsburgh outfit, construct mills up and down the Ohio River between Benwood and Wheeling, and eventually expand even more in Ohio and Pennsylvania. That is, until foreign steel entered the American market.

The death of steel in the Upper Ohio Valley was slow, inevitable, and very painful for thousands of steelworkers and their families. There were workforce strikes, buyouts, bankruptcies, and liquidations until finally, one day in 2012, RG Steel filed for federal bankruptcy protections and told their Wheeling-based employees to go home.

In some cases, those men and women were given the opportunity to return to their desks to collect personal belongings because, well, IT was done and so were they.

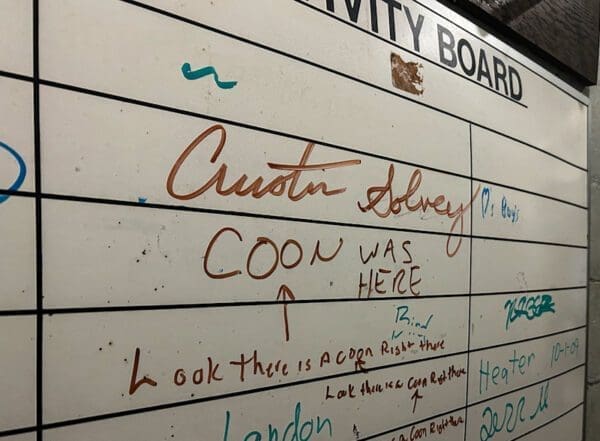

“When we first came in, we saw family portraits on desks, walking shoes under desks, and lunches in old refrigerators,” explained Steve Coon, owner of Coon Restoration and Sealants from Lousiville, Ohio. “At first, our instincts led us to try to return some of the people’s stuff, but it was no use. It was too long ago.

“It took us nearly two years to clear all of the debris that was left behind in this building,” he said. “Our 12 guys worked eight to 10 hours a day, too, but filing cabinet after filing cabinet, and desk after desk were emptied, and it took that long. That was a lot of years’ worth of business that was thrown through the trash chute, but no one wanted the stuff and it was time for the building to have a new life.”

Coon is working to transform the former office building into a residential high-rise with more than 100 one-and two-bedroom loft apartments. The project was announced four years ago, and was initially scheduled to be completed by now, but is only now moving forward in phases thanks to changes in the American economy. Interest rates have doubled, supply lines are limited, and several factors remain in limbo awaiting the country’s next election day in November 2024.

But the Historic Wheeling-Pitt Lofts, Coon insisted, have been designed and engineered, and the construction crews soon will begin on the first phase on the top floors of the structure. The completion date for all 12 floors remains unknown, but he and the building’s owner, Dr. John Johnson from East Ohio Regional Hospital, are committed to restoring the historic building.