It’s doing it again.

The two tubes of the quarter-mile Wheeling Tunnel once again are shedding their ceramic tiles and developing icicles on their walls where drainage is not supposed to take place. Just a decade after a three-year, $14.5 million rehabilitation project was allegedly completed by Velotta Co., Wheeling Tunnel is showing signs it may need attention in the near future.

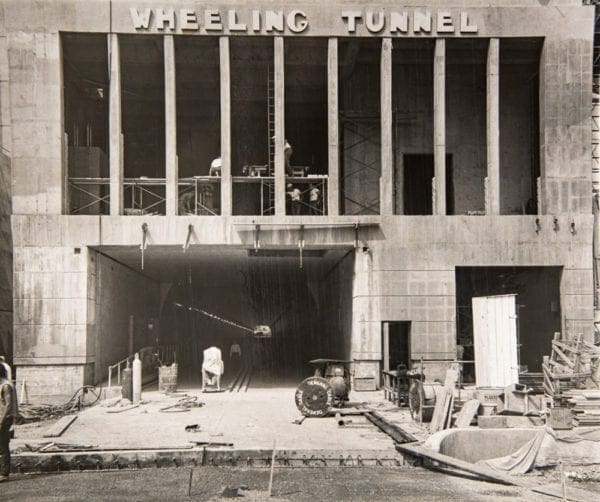

It was the first major reclamation project to take place on the tubes since Wheeling Tunnel was opened on Dec. 7, 1966, to connect to Interstate 70, but it was not included in the current three-year, $214 million “Roads to Prosperity” project that continues to address 26 bridges and ramps along the freeway’s 14.5 miles in Ohio County. Swank Construction will begin replacing or repairing spans on the eastbound side beginning Monday.

The crews with Velotta Co. encountered much trouble with removing and replacing the tiles, and it was only after the company was forced to order them from a German manufacturer because the ceramic product no longer was made domestically.

According to W.Va. Division of Highways District 6 Engineer Tony Clark, however, no such improvement project is on the district office’s radar.

“Wheeling Tunnel is inspected at least once per year, and the deficiencies that are found are noted, so if and when the people in Charleston decide it’s time to address those issues, they will know what the inspectors have found,” Clark said. “That size of a project is not something that would be handled on the district level. That’s a project that typically would be designed by either a consultant or by the people in Charleston.

“It is something that is always looked at, but it’s not been looked at very hard because of how recently the rehabilitation project was performed on those tubes,” he said. “But, just like a bridge, Wheeling Tunnel does get frequent inspections to make sure it is safe. It was actually inspected recently.”

Water Will Flow

Engineers determined 14 years ago that a community mine was located above Wheeling Tunnel, and the collected runoff was causing additional drainage issues for the tunnel’s original infrastructure.

That, of course, includes the drainage system, one that possessed 30 drains when initially opened 54 years ago. During the three years he served as District 6 engineer before retiring to enter the private sector, Gus Suwaid reported that only eight drains were operational when the Velotta crews finally left town after a six-month contract ballooned to three years of closures.

“I know the guys who are assigned to the tunnel do flush out those drains regularly. That’s one of the reasons we do have lane closures in the tunnel at times,” Clark explained. “There’s usually a lot of debris that comes from the roads and from the hill itself, so it’s a good thing for the drainage when that process takes place.

“Due to the enclosed nature of those tubes, that debris will settle in there, and if it’s not cleared frequently, it’ll cause even more issues with the drainage,” he said. “That regular maintenance prevents any further collapses of the drains that are still operational. I can say that Wheeling Tunnel is not experiencing issues as severe as those seen before that rehabilitation project that was performed about 10 years ago now. Everything seems to be functioning all right right now.”

The ‘Wheeling Wedge’ Project

Once the Velotta Co. failed to meet the original six-month deadline after beginning the project on Jan. 17, 2007, much discussion took place concerning the future of the tunnel system. In fact, one former state lawmaker, Orphy Klempa, requested and received a report for a proposed removal project for Wheeling Tunnel.

The report, developed in 2008, included an estimated cost of $89 million, but one of the major issues with it involved the removal of millions of cubic yards of earth and where to relocate it. One popular idea was to place the dirt on the north end of Wheeling Island since erosion has change that area’s landscape through the years.

That concept was erased, however, when the federal Environmental Protection Agency established regulations that disallowed altering downstream waterflow along creeks, streams, and rivers.

Many residents in the Upper Ohio Valley likely are familiar with the Sideling Hill wedge along Interstate 68 in western Maryland, a 340-foot-deep notch that now is one of the best rock exposures in the East Coast. Klempa, while a member of the state’s House of Delegates, compared the proposed removal project to Sideling Hill.

“I wouldn’t be opposed to the removal of Wheeling Tunnel if it was feasible to do so, and I have heard that there have been plans to remove it in the past,” Clark confirmed. “But now with what has been built on top of that hill, it would be more difficult to make that happen now. The DOT would have to buy a bunch of houses now that weren’t there before.

“To remove it, there would be a massive amount of material to deal with, for sure, and where all that dirt could go would be a very good question,” he said. “There’s not been any recent mention of that possibility, so I seriously doubt it ever takes place. So, yes, the tunnel is something that will need addressed in the future.”