The potential for a natural disaster along the Ohio River has been eliminated in Martins Ferry thanks to actions taken by the state of Ohio following a collective outcry by the valley’s local print, television, and radio media outlets as well as elected officials and a local environmental group.

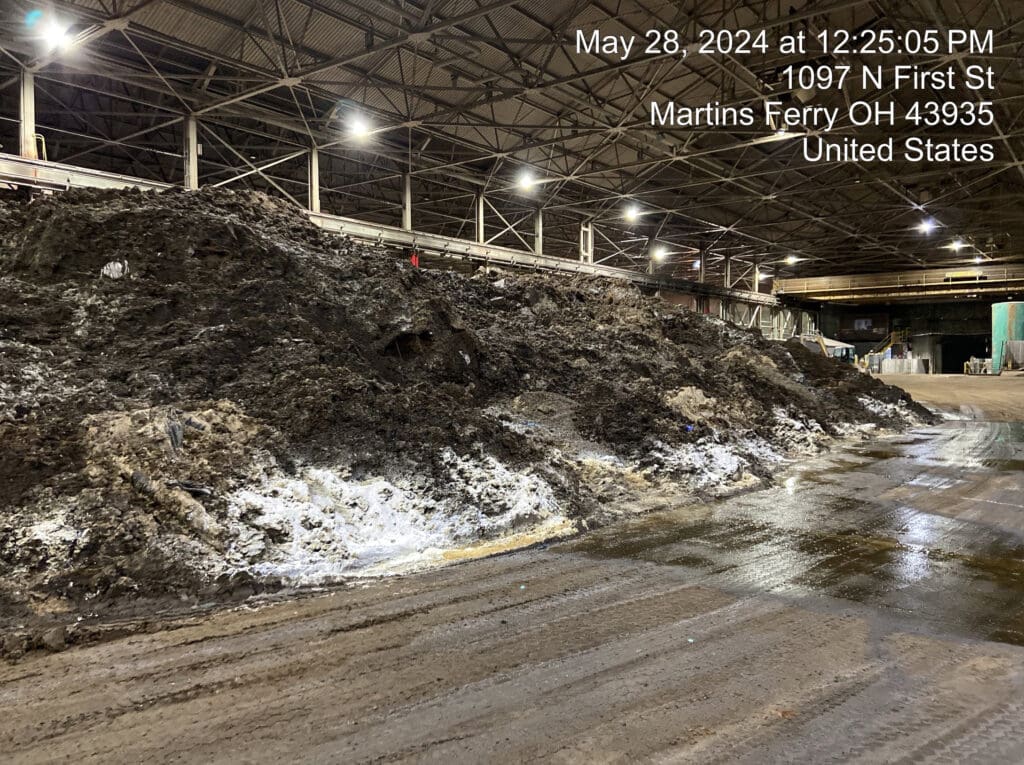

Austin Master Services initially was permitted by the Ohio Division of Natural Resources to store only 600 tons of waste at a time when the facility opened in 2015 but is now defunct and allegedly insolvent after stockpiling more than 10,000 tons of contaminated materials connected to the local fracking industry. The company had been hired to collect the materials from well pads in the Upper Ohio Valley and distribute them to facilities that properly dispose of the waste.

However, Austin Masters – a subsidiary of American Environmental Partners Inc. – halted operations and instead began storing the materials on the floor of their location inside the former Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel facility along the riverfront in Martins Ferry. The structure, which stands just 500 feet from the banks of the Ohio River, is currently owned by Mull Industries, and the area leased to Austin Master Services was abandoned in March.

“The looming disaster on our riverfront is no longer a threat, and I can’t tell you what a relief that is,” said Jack Regis, Martins Ferry’s auditor who served on the municipality’s council for 45 years. “When we found out exactly what was in that building, we knew there could be big trouble and I know our mayor, John Davies, did everything he could to get action down there. He worked hard on that and worked with the members of the environmental group (Concerned Ohio River Residents – or CORR) that came to council several times.

“When the flooding happened back in April, I think that helped wake up a lot of people,” the city’s auditor said. “And then after I went on the radio in July and talked about it with (former West Virginia lawmaker) Erikka Storch, that’s when they helped everyone understand the disaster that could have happened if the flood water had been higher than what they were. Thankfully, the waters didn’t make it to the floor of that building or the drinking water clear down the river would have been impacted.”

A number of different reports were published and broadcast by local newspapers and television stations concerning filed complaints, letters sent to state officials by City of Martins Ferry officials and by members of CORR, and Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost’s order that described the situation as an “environmental emergency” and ordered a cleanup process that never took place.

Belmont County Common Pleas Court Judge John Vavra granted a restraining order in the spring and then found company officials in contempt of court in the summer for failing to perform the cleanup. The judge had set a July 22nd compliance deadline or fines and jail time were possible. The company did pay a $25,000 bond to avoid further action.

“Once we knew there were thousands of tons of contaminated materials inside that building, we made the calls and wrote al the letters that were needed because we found ourselves between a rock and a hard place,” Regis recalled. “We’re just glad a lot of people listen to the radio and that Erikka was able to get everyone talking about it.

“Everything started rolling from there,” he said. “After the community really came together, it was good to see it get taken care of finally.”

The Clicking Sound of a Geiger Counter

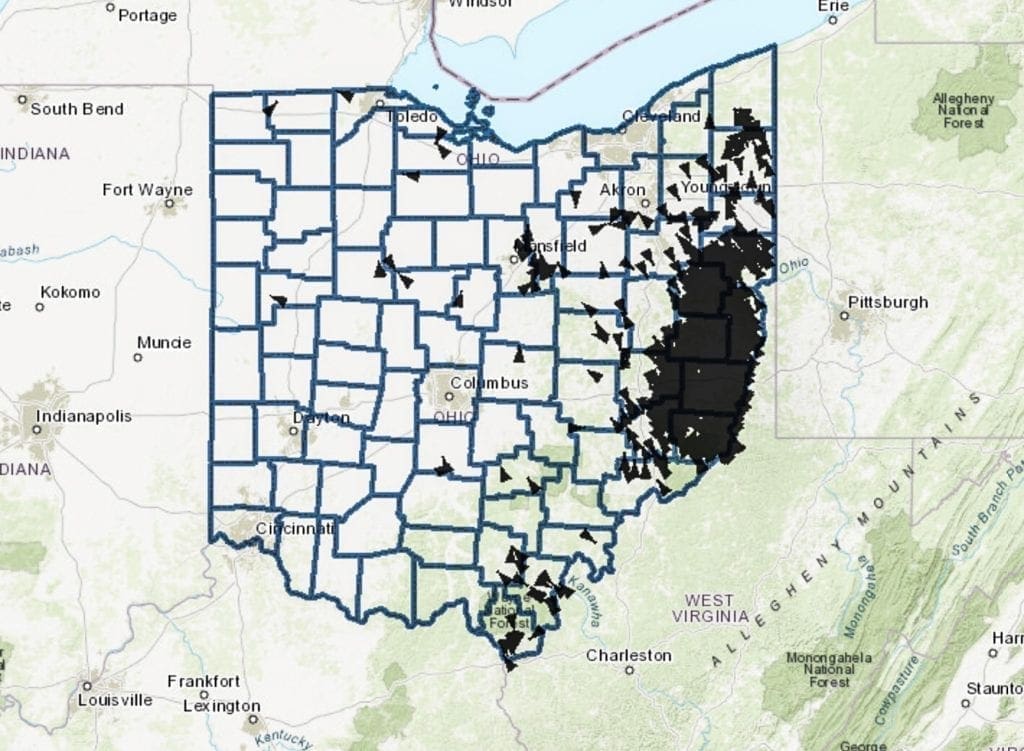

The oil and gas industries invaded the Upper Ohio Valley about 15 years ago, appearing first in Wetzel County in West Virginia before spreading north through Ohio County and west into East Ohio’s Monroe and Belmont counties.

At that time, “fracking,” or hydraulic fracturing, combined with horizontal drilling, were new practices for harvesting natural gas and oil from the Marcellus Shale play in the tri-state region. The process calls for the injection of a mixture of water, chemicals, and sand while drilling between 3,000-8,000 feet into the Earth.

Once the drilling and “fracking” operations are completed, a portion of the produced waste is, at times, radioactive and is collected by companies like Austin Master Services for disposal in federally regulated landfills. The members of COOR not only addressed Martins Ferry’s council a number of times about the illegal waste pile, but they also communicated with the ODNR and gained access of photos taken by the agency in late May.

“Those folks did great. They wrote letters, and they did all of the marches and protests and worked very hard to get everyone’s attention, and they brought in an expert who really knew his stuff when he met with us. He was pretty sharp,” he said. “He told us we had to get the attention of the state, and that sure did happen after The River Network and Erikka (Storch) got involved. They really pushed it over the top.

“I know Erikka called several officials in West Virginia who took action, and I know it was a topic on the radio for several days,” he said. “The squeaky wheel always gets the grease, I guess.”

The property was once home to Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel’s rolling plant where as many as 2,000 people were employed. The land has been owned by several companies since the steel company merged with Esmark Inc. in 2006. The riverfront parcels then were purchased by Mull Industries in late 2012, and a portion of the building – the “pickling area” – was demolished in 2017.

Although the environmental mess left behind by Austin Master has been cleared, Regis is unaware of what’s next for the property.

“The fact that stuff has been cleaned up is great news for the city of Martins Ferry,” the city auditor explained. “The owners of the building said they’ll never rent to a company like that again, so that’s the best news.

“That company (Austin Master Services) was there for a bunch of years and it seemed like everything was OK for a while, but then the former employees started to tell a different story,” he added. “Thankfully, we didn’t have a disaster.”