In the 20th century, the local newspaper bonded communities in small American towns. The news this week that Moundsville, WV is losing its 133-year-old newspaper, the Echo, is a harsh reminder of the country’s information crisis, and the struggle of Americans to maintain and nurture social ties.

Publisher Charles M. Walton told the Associated Press that he is “exploring options”. “We simply cannot get anybody to work there,” Walton told the AP. “I’ve been advertising for years for people. I don’t get any resumes. It’s just been a disaster to find anybody to even work part time.” (I’ve stopped by the Echo office a dozen times in my years chronicling the fascinating story of Moundsville, and Walton has always refused to talk to me.)

Start-up costs for online newspapers are minimal. You need a laptop, a phone/camera, and an internet connection. But there’s no easy business model anymore. Not enough Americans are persuaded professional journalism is worth paying for. It’s also hard to get qualified journalists to live in places like Moundsville. You’d need a business model that could generate a couple hundred thousand dollars in revenue. That can work in cities like Baltimore and Pittsburgh, but usually not in places with populations under 10,000. (My idea: A Marshall Plan for journalism. A billion dollars year could fund a thousand million-dollar newsrooms.)

For generations, the Echo functioned as Moundsville’s news source, community bulletin board, and what we now call a Facebook page.

In August, 1916, for example, the Echo reported that on Western Avenue “occurred a unique fight between a dog and a copperhead. The fight was waxing warm, though neither had the advantage until a resident of the street appeared, hit the snake with a brick, and then attacked it with a hoe. The snake was a very large copperhead, over three feet in length, and about three inches in diameter.”

A few months later, the Echo reported: “A valuable horse belonging to T.G. Hawkins of Roberts Ridge was instantly killed this morning, when a large tree feel, striking the animal. The other horse hitched to the wagon escaped and the wagon was slightly damaged. Mr. Hawkins had his team standing near Dietz store, while he was having some cider made, when the roots of the old tree gave way. The tree was an old landmark.”

Said Moundsville town historian Gary Rider: “The Echo provided information about local events that are not covered otherwise. Especially the loss of the obituaries that announce visitations. There are so many people that do not use Facebook that we feel a profound loss.”

The Echo, said Steve Novotney publisher of Ledenews, my favorite local news startup, based in nearby Wheeling, “put obituaries on the front page and they put our future on the front page, a.k.a. our children. It’s a sad day that the Echo has stopped publishing for everybody in Marshall County.”

The paper was founded in 1891, by James Davis Shaw, a businessman who’d done oil and lumber ventures in western Pennsylvania and West Virginia. (His obituary noted that he was a Civil War veteran, but did not say whose side he had fought on.)

On November 12, 1891, the West Virginia Argus noted: “We have received a copy of the Moundsville Echo. It is a nice neat paper and best of all is strictly Democratic. We wish brother Shaw great success in the good work.” The Weekly Register noted: “The Moundsville Echo is the name of a new Democratic paper just started at Moundsville, this State, by Mr. J.D. Shaw. It is a neat and newsy paper, ably edited, and will be a power for the Democracy in that benighted stronghold of Republicanism. We wish the Echo success politically and financially.”

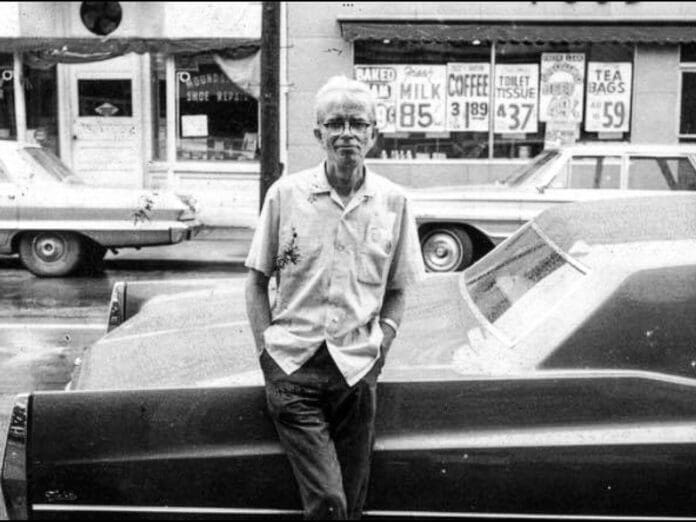

Shaw’s son Craig took over in 1917, and his grandson Sam in 1951. For over 40 years, Sam Shaw rode his bicycle around Moundsville collecting news. The Associated Press, profiling Shaw in 1984, called him “the sort of one-of-a-kind character that still pops up from time to time on the edges of our urban-oriented, cookie cutter society.” Shaw was a renaissance man who sang bass with the Ohio Valley Chorale, which toured Romania and Spain. Shaw was a bachelor who lived with his sister, Alexandra, and forbid liquor from his house, or the pages of his newspaper. Shaw wrote a daily news column called “Jots”. He said that “instead of just one boss, I’ve got 39,000—the people of Marshall County.”

Once, Shaw tried to shut down beer and gambling joints in town by printing the names of the people who’d been arrested. “My father got busted several times for running poker games,” recalled Pittsburgh-based artist John Mowder. “Nobody was embarrassed. The cops continued with their raids and the church population believed their tax dollars were being well spent.”

In any case, Shaw was a conscientious newsman who modeled the methodology of professional journalism for people in Moundsville. Now that residents no longer see one of their neighbors practicing journalism, they’re more likely to regard outside journalists with suspicion, unaware that reporters at institutions like the Wall Street Journal, Associated Press, and New York Times talk to as many sources as they can, check facts, and print corrections when they make mistakes. (As does this website).

Mowder left Moundsville over a half-century ago, but he always stayed in touch with the town though the Echo. “The Echo had been in my mailbox for 60 years,” Mowder told me. He recalled, while working as a flight attendant, seeing first-class passenger being offered the Echo and The New York Times. Many chose the Echo.

John W. Miller – publisher of Moundsville.org