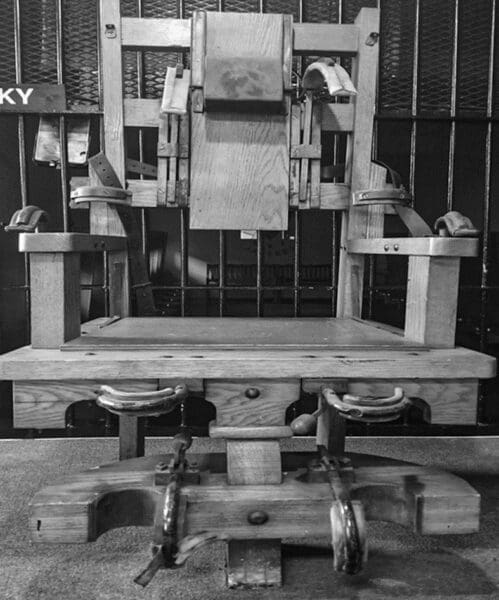

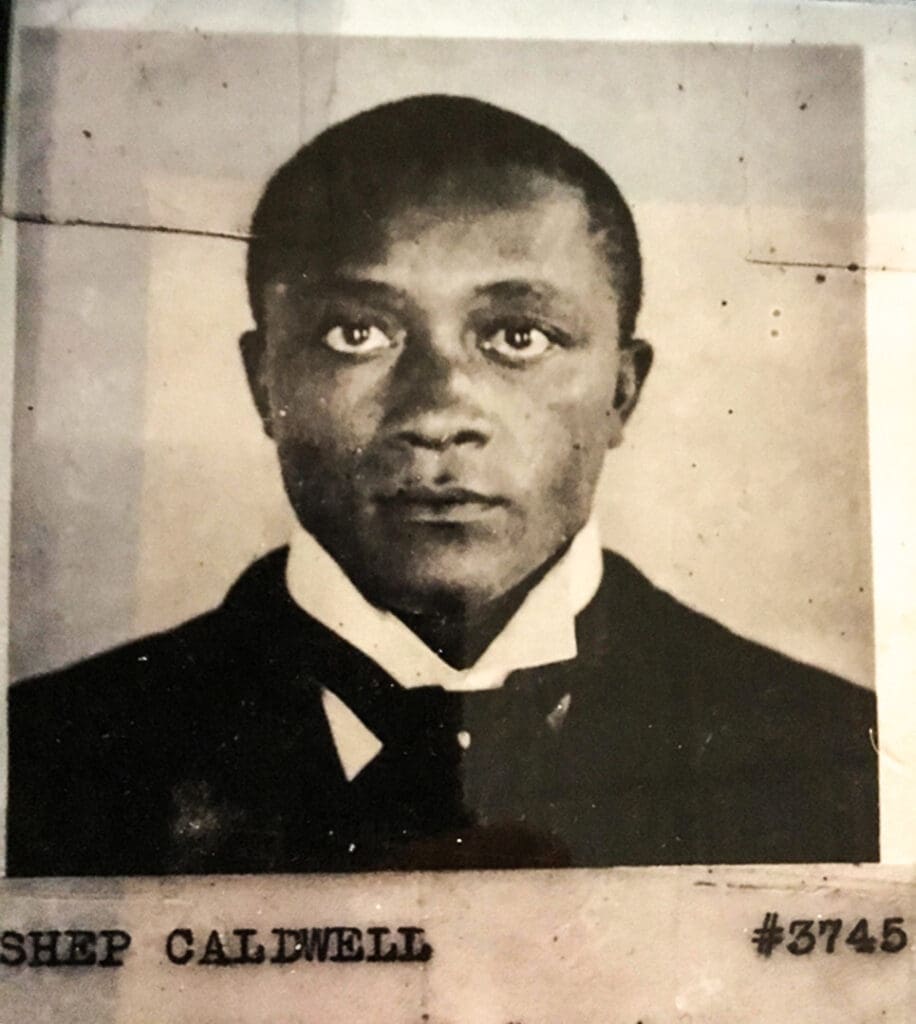

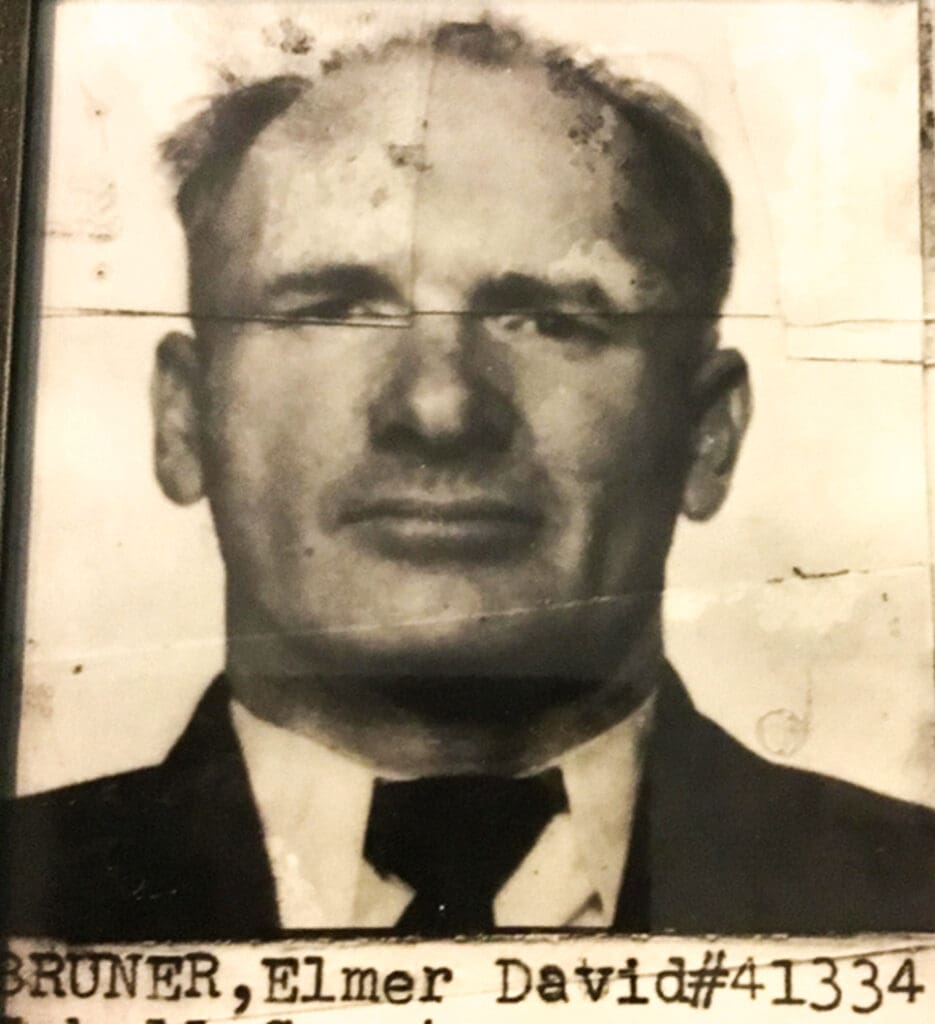

Ninety-four men crossed the line into eternity at the West Virginia Penitentiary by means of legal execution. The lives of ninety-four men ended abruptly either at the end of a tightly fashioned noose or amplified watts of electricity as they sat on “Old Sparky”.

Eighty-one were executed for murder, ten for rape, and three for kidnapping.

57% of those executed were Caucasian. 43% of those executed were African-Americans. This fact is alarming because only 8% of African-Americans lived in West Virginia at that time yet their deaths accounted for almost half of the executions.

There were fourteen men executed who either murdered their wife or their live-in girlfriend. Domestic violence ran rampant through the rough and tough Mountain State. In a snippet of Frank Broadenax’s last statement before he became the second man hanged in Moundsville was, “Let bad whiskey and bad women alone.”

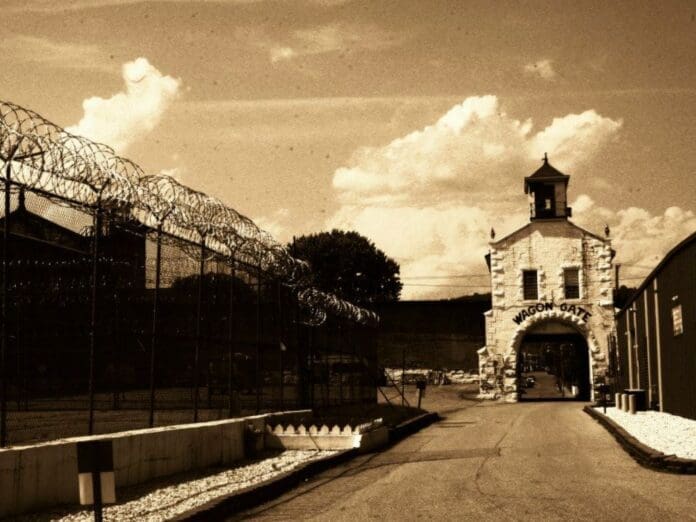

A prevalent legend of the West Virginia Penitentiary is that those who were hanged were done so in the North Wagon Gate. Documentation and facts refute that claim.

Many times, while I was leading tours in the vicinity of the North Wagon Gate, someone said, “My Grandmother watched one of the hangings here.”

I replied, “Sorry, but there were no hangings in the Wagon Gate.”

“But Grandma said she was here when she was a child.” (There were no children witnesses of any of the executions at the penitentiary.)

“What date did she watch the hanging?” I generally asked.

“1934.”

“There were no executions that took place in 1934.”

Many times, people either dismissed the truth of executions not taking place at the Wagon Gate or merely ignored the facts.

Before we examine the facts of the location of the executions it’s necessary to look at the last public hanging in West Virginia which occurred on December 16, 1897, in the town of Ripley. John Morgan brutally murdered Chloe Greene and her children, James and Matilda. A shocking aspect of the murders is that Mrs. Greene had taken Morgan in as a young child and raised him to adulthood.

Alice Prost was present at the scene of the crime. She was another of Mrs. Greene’s children from another father. Morgan attempted to kill her and her skull was fractured by the hatchet he killed the others with. Alice was able to escape from Morgan and run to safety to neighbors. If Alice suffered the same fate as the others, Morgan most likely would have not been caught and escaped death.

The motive for the murders was $56 which Morgan stole from the house as Mrs. Greene recently sold some horses. Morgan faced trial and was condemned to death two days after the grisly murders.

Six weeks later, he faced the gallows. Before he was hanged, he managed to escape from the jail but was recaptured after a couple of days.

Morgan thought highly of himself and sold his story for $25 as he wanted to buy a suit to wear when he was hanged. When the day of the hanging arrived, the small town of Ripley which usually had 700 residents, was flooded by 5,000 people.

The newspapers recorded there was much uncouth and raucous behavior. The scene was described as carousing and almost 2,000 women acted in an unladylike fashion. There were vendors selling souvenirs and food. The outrageous behavior at the last public hanging convinced the West Virginian politicians to abolish public executions in 1898.

From that point, all executions in West Virginia were to take place at the West Virginia Penitentiary.

One documented proof that the executions did not take place in the North Wagon Gate comes from the October 10th, 1899 edition of the Wheeling Register. The brief article stated:

“In the presence of a limited number of spectators – the execution took place in the new building erected for the purpose under the law passed by the last legislature and was successfully carried out under the supervision of Warden Hawk.”

Earlier in 1899, the political leaders of West Virginia were fearful the situation that happened at Ripley would take place in Moundsville. On January 18th, 1899, Mr. Darst introduced Bill Number 5 to the House of Delegates in Charleston to have the executions in the penitentiary. On February 2nd, there was unanimous consent.

On August 13, 1899, the Wheeling Register quoted Warden Hawk that the execution building cost $6,000. There was a separate death house located where the razor wire, chain linked bull pens (recreational yards) for the North Hall inmates are currently positioned. This is where the hangings and electrocutions occurred. The building was torn down in the early ‘70’s when many of the older structures of the North Yard were razed.

Another proof that the executions did not occur in the North Wagon Gate is that they were not open to the general public. In order to attend an execution, one had to write the warden and request a “ticket”. This ticket allowed them to go inside the death house and witness the condemned die.

No one under the age of 18 years old was allowed to witness an execution at the West Virginia Penitentiary and there were only 10 women permitted to do so. Wardens received letters asking if women could attend but most of their requests were denied. Some wardens allowed family members of the victims to attend and some did not. At each execution, there are recorded lists of everyone who was present.

The greatest proof the North Wagon Gate was not the location of the executions by hanging is the building itself. There are two major items that disprove any hangings occurred within that structure.

The first proof is the stairway that leads to the second floor of the Wagon Gate. It is a narrow set of white steps. The passageway is not wide and cannot accommodate people walking side by side. There were several inmates who needed assistance as they took their final steps toward their imminent meeting with death.

One of the most notorious inmates executed was Raymond Styers on May 13, 1938. He was the only Moundsville resident to be hanged at the penitentiary. Sadly, as a youth he was in and out of a juvenile detention center in Pruntytown which was originally named, The West Virginia Industrial School for Boys.

As an adult, he spent time at the penitentiary because he illegally carried a pistol, broke into garages, and burglarized them. The crime that led to his death sentence was much more heinous than his earlier criminal behavior.

He and Tom, his brother, and Ken Lightener ventured to a beer parlor in Wheeling where they lost money as they gambled. They returned later that evening as Styers wanted to steal his money back. He went inside while Lightener and his brother waited by the street.

When Styers was inside the darkened parlor, he saw Anna Bris. She was the wife of the owner and the mother of five children. In cold blood, he shot and killed her. For this crime, he received the death penalty.

During Styers final confinement, he was belligerent and defiant. He boldly proclaimed, “They will never hang me. My neck’s made of rubber. My neck might stretch, but it will never break.” He was wrong.

As Styers was led to the gallows, he refused to cooperate and had to be put into a straightjacket. He was carried up the steps to the gallows where it would have been impossible to lift and move a struggling man up the steps in the Wagon Gate.

The second major reason why executions by hanging could not have taken place at the North Wagon Gate is because there were eight multiple hangings. Two of the executions were of three men. There was and is only one opening in the Wagon Gate. If the hangings occurred there, they would have needed at least three openings.

So, how was the rumor kept alive there were hangings in the North Wagon Gate? One of the people working there decided to hang a noose from the opening and the story grew from there. While it is interesting to look up and see a noose dangling above, it was merely a prop to illicit a chuckle.

One may ask then what was the purpose of the opening trap door? Caskets were stored on the second-floor area of the Wagon Gate and were lowered down when needed for a dead inmate. An executed man’s casket most likely came from the Wagon Gate but it was not their final place on earth.

The proof of the legislative and newspaper records bust the myth of the hangings in the North Wagon Gate as well as the physical structure of the building.