When a “bad batch” reaches the Wheeling area, it often results in multiple overdoses, sometimes death, but also a search for more from which it came.

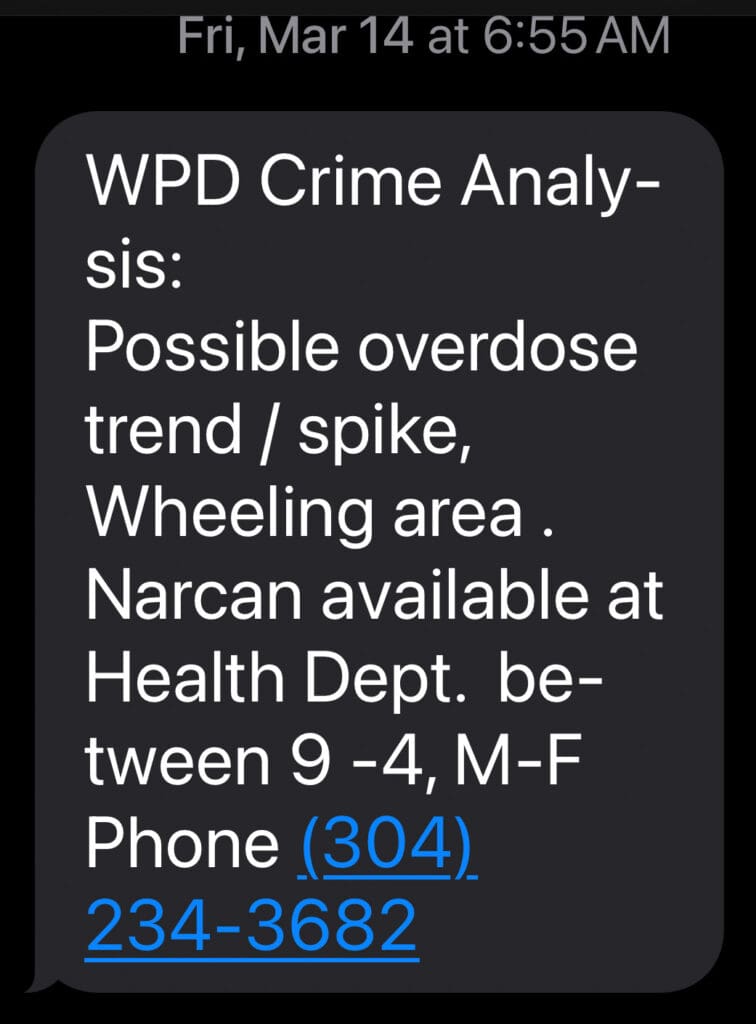

That was the case eight days ago. The Wheeling Police Department distributed a text message early on Friday, March 14, stating a “Possible overdose trend/spike, Wheeling area”, and, according to Ohio County Sheriff Nelson Croft, it sent all law enforcement into search-and-apprehend mode.

“When that happens, it’s all hands on deck with our interdiction guys and our drug task force trying to figure out where it came from. A lot of times, no one will tell us anything even if their friend just died from it,” said Croft, who is now in his third month as Ohio County’s sheriff. “I bet as soon as we leave, they go try to get their own, and that’s really something I’ll never understand. I’ve looked into the mind of an addict as deep as I can, and I still can’t get there.

“They think they’re invincible,” he said. “And I guess they are until they’re not anymore.”

Fentanyl, according to the federal Drug Enforcement Agency, is a potent synthetic opioid drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as a pain reliever and anesthetic. “It is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin as an analgesic,” the agency’s web site states, and Croft believes dealers now compete against each other by adding the manufactured narcotic to what they street sell.

“When we see a rash of overdoses with deaths, we know someone has been selling something with too much fentanyl in it. If we can bring someone back, one of the first things they do is start swinging at whoever they see,” Croft said. “A bad batch is usually meth or heroin mixed with too much fentanyl. If we get there on time, it may take a few doses of Narcan, but if we don’t, we lose someone else.

“And this might not make much sense to a lot of people, but there have been times when someone’s friend overdoses, the first thing the friend tries to figure out is who the dealer was because they obviously have powerful stuff,” he said. “It may sound crazy to a lot of people, but it makes sense to addicts.”

Incarcerated Recovery

In January 2024, members of the Northern Panhandle Continuum of Care organization conducted a 24-hour count of homeless individuals living in the Wheeling area, and the number was a little more than 100 individuals.

The same exercise was conducted this past January, and the survey indicated there were 149 individuals living homeless in February, including five in Hancock County, seven in Brooke, 122 in Ohio, four in Marshall, and 11 in Wetzel County. Ohio County, Croft acknowledged, has the highest amount because of the services available in Wheeling most days per week.

“I don’t think there’s too many in this region who hasn’t been touched somehow by an overdose or an overdose death. I know so many people who have lost family members, friends, and co-workers,” Croft said. “We know it started with the opiate pills on the street, and then it progressed to heroin because heroin is much cheaper, and it still filled the need of the addiction. And then methamphetamine came into the area and took over.

“But now we’re seeing fentanyl in everything,” the sheriff explained. “These dealers are putting fentanyl in cocaine, marijuana, heroin, meth, and even in the pressed Xanax pills, and in too many cases, it’s killing people.”

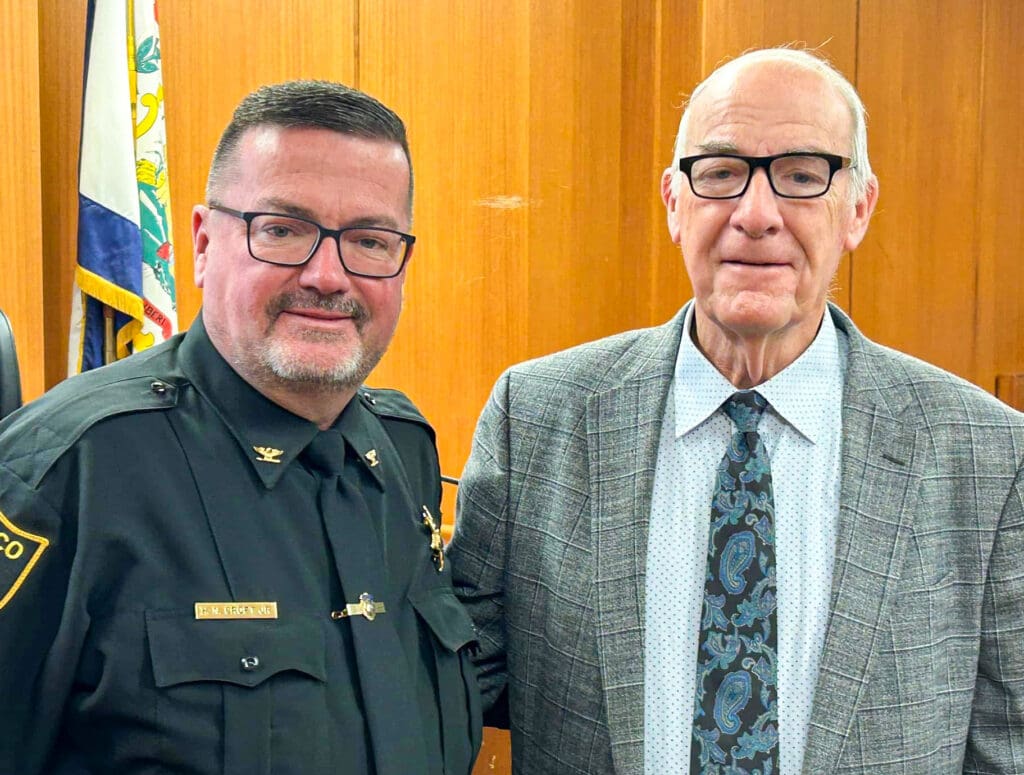

Dr. Norman Wood, a Marshall County resident who has an extensive background in law enforcement, drug interdiction, and in the medical field, has offered to state officials in West Virginia his ideas for a scientifically proven program for drug rehabilitation. The solution, he believes, would involve a new division in the state’s Drug Court and regional hospitals where convicted rug addicts could recover while incarcerated.

Sheriff Croft strongly favors Dr. Wood’s proposal over what’s taking place now in the Wheeling area.

“I am familiar with the idea and I support it 100 percent,” the sheriff said. “What we’re doing now sure isn’t working. I know something who works at a state prison, and he told me that in one week they had 12 overdoses in the prison where he works. Now, how does that happen? Someone had to smuggle in a bad batch. That’s why addicts stay addicts in jail and in prison.

“In jail, you just have to know who to ask and make the deal because he tells me there’s as much drugs in jail as there is out in the public,” Croft explained. “We need the regional hospitals Dr. Wood has suggested so convicted addicts really get better while incarcerated. What we see now with people living in tents in a camp is not working, so I hope people can work together to do the right thing.”

Dr. Wood has distributed the information directly to W.Va. Gov. Pat Morrissey, too, and the physician is hopeful he’s asked to further explain the program that could work in affected states across the country.

Croft is confident Wood’s idea would save lives if implemented.

“I do hope I see the development of a regional treatment system for addicts because jail is just a revolving door until you finally overdose and die. It’s a very sad situation,” Croft insisted. “We’re doing these people a disservice, and we should fix it.”