The other evening I was driving home after my grandson’s baseball game. Because the game had extended into extra innings, I was out later than usual, but it was a beautifully balmy evening with the temperature still hovering over 80 degrees at 9 p.m. It was my kind of weather, and so I had all the windows down and the moon roof open.

As I drew near one of the city’s largest cemeteries, I noticed numerous floodlights had the place almost as light as high noon. Adding to the strange sight were four or five large bulldozers and equally as many backhoes positioned in various spots among the tombstones. My innate nosiness as a journalist being immediately aroused, I slowed down, drove through the gates to the cemetery, and pulled up to the nearest excavation site. Standing beside a backhoe was fellow smoking a cigarette and wearing a T-shirt with the initials USGOFEOBSCR emblazoned on it.

He didn’t appear to be a particularly foreboding chap, and so I got out of the car and approached him.

“Hi, my name is Bill. How are you this evening, sir?” I said, extending my right hand.

He looked me up and down, threw his cigarette to the ground and stomped it out before slowly extending offering to shake hands with me.

“Hullo,” he said. “What brings you out here now? The place is supposed to be closed.”

“I was just on my way home from a little league baseball game and saw all the commotion in here.”

“Kind of nibby, aren’t you?” he said.

“Well, I guess so,” I said. “But you must admit that a cemetery filled with floodlights and heavy digging equipment this time of night is a bit curious.”

“I suppose, but if I had my way, I wouldn’t be here,” he said as he lit another cigarette.

“Do you mind my asking why you are here? And by the way, what’s your name?”

“Name’s Flem, and if you don’t know why we’re here, you must not read or watch the news.”

“What did I miss, Flem?”

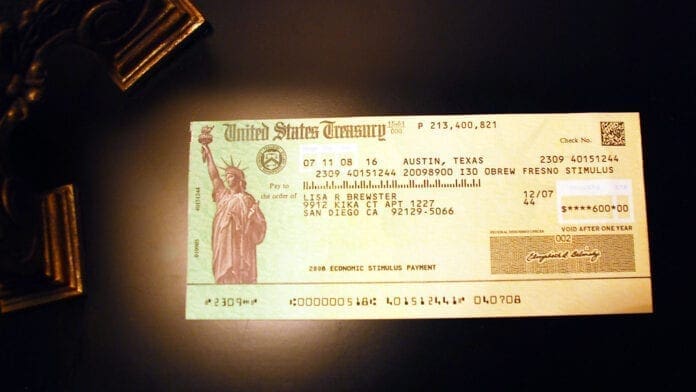

“Well, in its inimitable wisdom the IRS mistakenly sent COVID-19 stimulus checks to more than 1 million dead people.”

Using every ounce of strength I had, I suppressed laughter and managed to choke out, “What?”

“That’s right,” Flem said, and he did laugh. “Apparently they sent out the checks using a system that hadn’t been touched since back in 2008, and thus there was no synchronization between the IRS and the US Treasury. So as a result of that screw up the same thing going on here is also happening in cemeteries all over the country.”

“You mean…” I started incredulously before he interrupted me.

“…that’s right. We’re here to collect those checks from the dead people. See my T-shirt,” he said.

“I was wondering about that,” I said.

He dropped his cigarette to the ground, stomped on it, puffed out his chest and said, “USGOFEOBSCR stands for United States Government Office For Exhumation Of Buried Stimulus Checks Recipients. We’re here to clean up the mess the IRS made. Now I’ve got to get back to work.”

“Oh, sure,” I said. “Thanks a lot for taking the time to talk with me, Flem.”

“Aw, don’t mention it, Bill. As you may have guessed, most of the people I encounter in this job don’t say much.”

This time I did laugh.

“Where do you go from here?” I asked as he climbed into his rig.

“We have another cemetery in this city tomorrow night, and then it’s anybody’s guess where they’ll send us.”

“Good luck to you, Flem. I really enjoyed talking with you.”

“You take care, Bill,” he shouted over the roar of the backhoe’s engine.

But I just had to ask before I left because Flem was such an unusual name.

“Hey, Flem” I yelled. “One more thing. What’s your last name?”

I had to strain to hear him over the noise of the backhoe, but his answer was unmistakable. “SPADE.”

“Perfect!”