(Publisher’s Note: A new chapter to this series of stories will publish in the near future so we believe in order to get new readers to discover the series, the best thing to do is to re-publish it beginning today and continue during this coming week. One of the main reasons why Gwen Wood, her daughters, and her friends and family agreed to tell this story was to raise more questions in hopes additional information about this accident would flow their way … and that has taken place thus far.)

(Publisher’s Note: This is the third in a series of articles that will examine the passing of 19-year-old Colby Brown, a 2018 graduate of Cameron High School, who attended Marshall University in Huntington. Colby was pronounced dead on Aug. 26, 2019, after paramedics treated him in the middle of Interstate 64.)

Darby Brown and her brother Colby had a thing, and it was the same thing he had with Shelby and his mom when it came to hitting the gym. The little brother babysat.

“When are you going to gym? What machines are you using? How long are you there? How many reps? His questions were non-stop, but I know it was because he wanted me to do it the right way,” Darby said. “So, we would Snapchat each other when we were at the gym to be accountable. It really was one of our things.”

But then there was August 26, 2019. Colby Brown was pronounced dead shortly after 7 p.m. after he worked out at his gym, attended both of his classes during the first day of his sophomore year, and played video games with five friends.

Always Responsive

“We were in contact on Snapchat at about 3:30 p.m. that day, but then at 6:35 p.m., I sent him a photo of me at the gym,” Darby said. “Usually, he would send something back that was supportive, but not that time. I didn’t hear back from him, and yes, I did think it was odd at the time because he always replied, especially when it came to the gym.

“That day, though, the photo I sent him was opened, but there was no response, and I thought it was odd and rude that he wouldn’t answer me because he always did without fail,” she continued. “I mean, why would he open my message and not respond? Now, though, I’m not so sure it was him who opened that message. And then we found out that after that, his location was turned off on his phone right around the same time.”

The end result is what is known. Colby Brown died that day on Interstate 64. A young lady who stopped when seeing him fall to the cement knelt over him during his final breaths.

Not Adding Up

“It doesn’t add up, and that’s why I still don’t know what really happened to Colby, and that is what is so infuriating,” Darby said. “I have all of these theories in my mind, but I don’t have enough information to make sense of a single one of them. I don’t know, and that’s why we’re so desperate for more information so we can know where he was and maybe why this happened.

“It’s just not right. It’s been over five months, and we still don’t know anything new other than I don’t have my brother anymore,” she said. “And the state police still have not given back his phone because the investigation is said to be ongoing, but I wish they would just give it to us so we can go find the answers like we have been since this accident happened.”

‘Thank you, sir. May I have another?’

Pledging a fraternity was a discussed topic.

His mother and his sisters were anti-frat for reasons of their own, but Colby was surrounded daily by members of the Alpha Sigma Phi fraternity. His roommates and the boys with whom he was playing video games on the day he died, were mostly Alpha Sig members.

If Colby had, in fact, decided to pledge to join his friends, no one in his immediate family was informed.

“He had told us that he wasn’t really interesting in joining a fraternity, but all of his friends were fraternity members of Alpha Sigma Phi,” Gwen explained. “One of his roommates was the president of the fraternity, so I guess it is possible that he finally gave in and decided to pledge.

“But if that turns out to be the truth, I’ll be very surprised,” she said. “But he was growing up, living on his own, and was making his own decisions. I do not know if he made that decision on the day he died, though.”

Alpha Sigma Phi is a national fraternity with more than 8,000 undergraduate members and 56,000 living alumni, according to the organization’s website. It was founded on Dec. 6, 1845, at Yale University, is the 10th oldest national fraternity in the nation, and is one of 12 fraternities at Marshall University.

Investigations into behavior and hazing have taken place at Marshall concerning fraternities and sororities during the past five years.

Jon Crow, once a family friend and a classmate of Colby’s, did not say anything when he visited for Colby’s funeral about the fraternity or whether or not he had decided to become a pledge.

“All he told us was the same story over and over again,” Gwen recalled. “They all smoked a bowl of weed, and then Colby went downstairs because he didn’t feel good, and then he just left. That really doesn’t sound like something Colby would ever do.

“I mean, he never just left without saying goodbye, so I don’t know. Obviously, we know he did leave, but like that?”

Herd Life?

The legal drinking age in West Virginia is the same as it is in the other 49 states – 21 – but that wasn’t an obstacle for Colby and his friends, Darby insisted.

Why not?

“Colby found out during his freshman year that there are bars in Huntington where you could get a special card and those bars will allow you to drink if you are pledging the right fraternity,” Darby claimed. “And yes, even if you are underaged. And Colby did get one of those cards from one of his friends, but he told us he used it only to go to that bar and that he was never really going to pledge the fraternity.

“I told him that it wasn’t his type of thing and I really didn’t want him to get involved with it because you hear so many stories from all over the country. But I also know someone from WVU died because of hazing. Nolan Burch died because of that culture, and that made me worry about my little brother,” she said. “When it came to college, I was the person he went to because I graduated college just before he was a freshman at Marshall.”

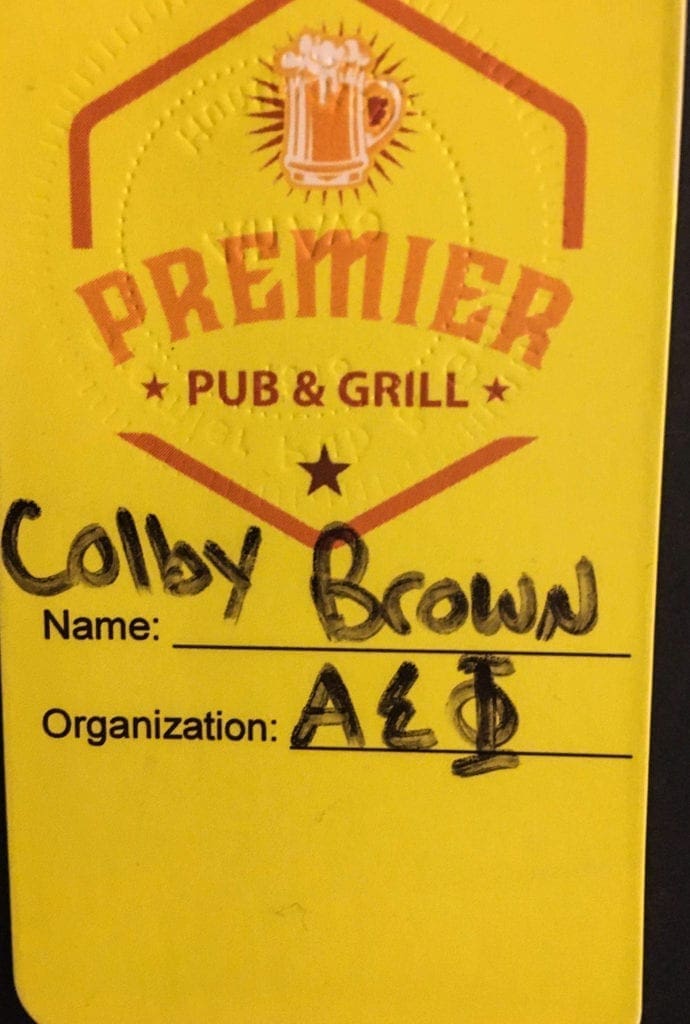

Once his personal belongings were collected from his apartment and his car, Gwen did find a new card for the Premiere Pub & Grill with no name or organization listed. The question Colby’s family has asked is whether the new card was another gift, or was it earned somehow this time?

“I don’t know if he had to do something for it. Maybe,” Darbie said. “But I don’t know if he had to do something his freshman year to get that card. He just acted as if he just had to be interested in pledging to get it, but as for his sophomore year, that’s something we never talked about.

“His freshman year, he had a card for Jake’s, but that bar closed down, but he had a couple of cards in his wallet from a place call the Premiere, and one of his roommates, Jon Crow, was a bouncer at that place,” she explained. “If he went down to Huntington with the intentions of pledging that fraternity, he hid it from us, and that wouldn’t have been like him. He wasn’t a secretive person with us.”

Heroin in Huntington

The entire state of West Virginia has gravely suffered from the opioid crisis, but the Huntington area? It was stricken. The largest city in Cabell County is met with many of the same challenges law enforcement encounters here in Ohio County because of its proximity to state borders.

One after another. One day in 2017, more than 20 people overdosed on opioids laced with fentanyl in Huntington, and the city since has been a focus during the epidemic.

But opioids? Heroin? Colby?

“The only way he would do anything like that is if he didn’t know it,” Darby insisted. “And that stuff didn’t come back on the first toxicology report that we finally received from the private investigator. All that was on it was marijuana and nothing else.

“I know there was mention of him doing mushrooms, but that isn’t listed on that report either,” she continued. “He liked weed, and we all knew it so that is why we are anxious to get the second toxicology report that hopefully will be completed soon.”

In 2017, 1,019 West Virginians died of an opioid overdose, and in 2018, 900 perished, according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Quick response teams are operational in 22 of the state’s 55 counties, and the first squad was formed in 2017 in Cabell County. A paramedic, a law enforcement officer, and a recovery coach are involved.

“I know Huntington is ground zero for opioid deaths, but I also know my brother would have never gone there,” Darby said. “He was too concerned with his health and his body to ever do anything like that of his own accord. Now, was he slipped something without him knowing? We don’t know.

“Colby has seen people in our family struggle with addiction, and it’s something he paid attention to and something he always said he would avoid at all costs,” she said. “I know he would not get on that path of opioid drugs even if he wanted to experiment with something. That was something he would never get involved with; that I know. He saw it destroy too many people.”

A Shiny Penny No More

Gwen’s voice changes when she begins to talk about her son. It lowers into persistent somberness and often is difficult to hear during conversations.

She and Colby’s sisters are not alone in their sorrow. Penny, a canine Colby took to Huntington with him for his sophomore year, has changed, too.

“At first, Penny would look for him any time she heard a car door or an engine rev up,” Gwen said. “But now, she acts depressed and just wants to sleep all of the time. She’s not the same dog she was, and she’s a 6-year-old Boxer. I just think she’s sad and that she’s lonely. She misses her best friend.

“She doesn’t like to be left alone, either,” she continued. “Penny seemed angry during the first few weeks, but now she just seems so damn sad.”

The family has been contacted since this series of stories began on January 11, and they are hoping and praying that more people step forward with any information they may know to be true.

“That’s really what we want, so I’m glad that some of his friends are now reaching out to us to help us fill in the parts of his timeline that we don’t know yet,” Darby explained. “No piece of information is too small, either, because this is a big, giant puzzle we’re putting together ourselves because of the lack of help from the investigators.

“If you talked to him the day before or the day of Colby’s death, that’s important to us, and if you talked to any of the people he was around during those days, that’s also important to us,” she insisted. “I would love to hear from more people; that’s for sure.”

(Photos provided by the Brown family)