(Publisher’s Note: The 12-part series, “The Children of Wheeling’s Mob Era,” will be re-published each evening over the next two weeks so those who missed some or all of the chapters will have another chance to read it. A collection of Steve Novotney’s mob stories over the years will be released in book form this summer.)

8

A Truck Stop’s Convicted King

The days were always greyed by the fumes filling the skies around those mechanical monsters coming and going east and west along the freeway that finally connected through Ohio County. The trailers were filled with what people wanted and needed, and the truck drivers lived in their cabs when they weren’t sightseeing a bit in Triadelphia, West Virginia.

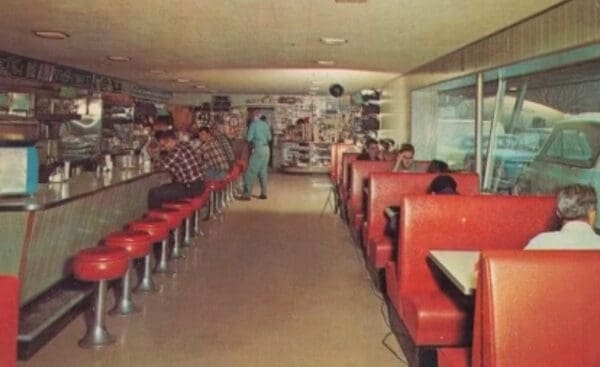

There were car-sized potholes in all corners of the Windmill truck stop, constant chaos with fill-ups and semi-maintenance, and a homestyle diner inside the round with steak and eggs frying on its flat-top grill all day long. The industry was dominated by white American males in the 1970s and ‘80s, and they wore their boots and blue jeans, flannel shirts, and white netted ballcaps back and forth across the United States.

And while stopping for an evening in the middle finger of the Mountain State, many of the men visited the King of the Road Health Club, an operation down the road from the Lucky Lady Lounge that rested across West Alexander Road from the truck stop’s main entrance.

“But it wasn’t the kind of health club that had a weight room and a sauna,” smirked Bill Kolibash, a former federal prosecutor based in downtown Wheeling. “The King of the Road sold something completely different than good health, and the place was very, very popular.”

That’s because the King of the Health Club was a full-service house of prostitution with approximately 12 beds and females from a number of cities east of Missouri. A 45-year-old man named Joseph Vincent Truglio was the brothel boss, and when he was indicted in November 1982, Kolibash also charged Phillip Pavilack of Triadelphia, Roberta Mae Ebright of Wheeling, Florence Hess of Bellaire, and Paul Demko of Wheeling.

The U.S. Attorney alleged the operation offered females free jail bail if arrested for prostitution, supplying aliases and false addresses, providing food, lodging, shelter, and transportation, free and regular medical care, and high wages for services rendered. Pavilack was described as the “courier,” according to court documents, and Ebright and Hess were “spa managers.” Demko, too, was alleged to be involved with a number of areas of the operation.

The health club opened in the mid-1970s and operated undetected until its popularity grew to the point where a two-year investigation was launched in 1980 by Kolibash and his organized crime task force.

“It was brought to us after the deputies with the sheriff’s office saw what they saw while patrolling the truck stops. They would tell us what they saw going on up there and if the girls were going to the men, or if the men were going somewhere for the girls,” said Kolibash, whose book “Justice Never Rests” is scheduled for a January 28th release. “That’s how we found the King of the Road. The guys were going to the place one after another, and from what our people saw, it was pretty obvious to everyone.

“Now, there were the freelancers that went from truck to truck, and we found out that had been the case as soon as the Windmill opened and those females were local and never connected to Truglio,” he said. “But the professionals were inside the King of the Road and it had been there for several years before we could build a case against it.

“The truck stop and the area around it had always been a very busy place with a lot of moving parts all day and all night long, so I’m sure not a lot of people noticed much, and I doubt anyone cared.”

Local, Not Local

Except for Truglio and his mix of managers, the rental rooms at the King of the Road were filled with no-named strangers, and that’s one reason, Kolibash believes, the brothel remained under his radar for so long. The customers were mostly as transient as their for-hire interstate transit allowed, and the females were out-of-towners, too.

While Wheeling’s mob bosses – first “Big Bill Lias” and then Paul Hankish – operated as many as 24 prostitution locations in Center and South Wheeling, those operations were not connected to Truglio’s single house of sexual favor whatsoever. The majority of Truglio’s females were delivered, in fact, from cities like Louisville, Ky., Detroit, St. Louis, and South Bend, Ind., according to the information collected by Kolibash and FBI Agent Tom Burgoyne. The women, he proved, were recruited for the state-border brothel, and many voices on Citizens Band channel 18 took care of the business’ grassroots marketing campaign.

“We knew they were bringing in the females from all over, but mostly from South Carolina, and a lot of them were Asian. We found out many of them were from Thailand, and they would come to this area from the Carolinas for whatever reasons,” Kolibash explained. “We knew that some of them came here after working around military bases along the East Coast, but I don’t think we knew which ones for sure.

“I’m sure the madams had phone conversations, and when they flew up here, one of Truglio’s guys (Phillip Pavilack) would pick them up and take them to the Holiday Inn that was just up the road,” he explained. “After they got settled in their rooms, they would be taken to the King of the Road, and they’d go to work. It was a pretty smooth operation.”

From what Kolibash and Burgoyne discovered, work “uniforms” were provided to the females, and so was medical care.

“Our investigators found out Truglio had a doctor for the prostitutes that worked for him in Dallas Pike, and when the girls came down to his store, that’s when some of them would have their monthly exams and get their scripts for whatever. The others took place up at the King of the Road,” Kolibash said. “They brought them in from a lot of different cities, and from what we found out, Truglio never recruited any of the women that worked for Hankish.

“Prostitution was pretty big in Wheeling in the 70s and 80s, and it really didn’t attract a lot of attention. People knew about it,” the prosecutor said. “But what Truglio had going up in Dallas Pike was always a very busy place. But, really, it wasn’t local. Most of the men were on their way through, and the women were from outside this area.

“That meant there weren’t a lot of people were talking about their big night out in Dallas Pike. There was no word of mouth on the street about what was going on up there.”

As far as federal authorities knew, that also meant Truglio was never challenged with a turf war against Hankish and his mischievous men.

“What Truglio was doing with the gambling and the prostitution was completely separate from the Hankish organization, and we’re not really sure why that was OK with Hankish since Truglio operated his (gambling) book out of his store on Market (Street). But when we started investigating Truglio’s criminal activity, we already knew who he was and that he had been a criminal for a while – but never connected to Hankish in any way,” Kolibash reported. “He was arrested several times before; one time for robbing a post office in Steubenville.

“Truglio’s business in downtown Wheeling was called ‘True’s Exotic Attire Shop,’ so I would think he had everything the females needed there,” he said. “The shop was between the McLure Hotel and the Victoria Theatre in a building that’s not there anymore, and that was his day job that was legitimate.

“Truglio and Hankish were both old-school criminals, so maybe that’s why they left each other alone. Maybe, somehow, they respected each other.”

‘See the Man Behind the Desk’

Interstate prostitution, racketeering, and several White Slavery Act charges were listed after the two-year investigation, and federal and state authorities conducted several raids following Kolibash’s announcement on Nov. 19th. He, in fact, attended the nighttime incursion at the King of the Road.

There were 31 indictments against the brothel owner and his employees that were returned by a federal grand jury in Elkins, and reporter Theadiane Taylor’s article in The Intelligencer on Saturday, November 20th, 1982 featured a blaring headline: “Truglio Faces 155 Years on Charges”.

“Once we had enough probable cause to get and execute a search warrant, we went in on the raid at his businesses and his home,” Kolibash recalled. “We got the records and everything else out of those locations pretty quickly, and I remember sitting outside in Dallas Pike with all the state police there with their (light) globes flashing. Believe it or not, there were guys pulling up and asking us if the place was open. I told one guy to go see the man at the desk for his membership card and he actually went inside.

“Well, the membership card was a subpoena to appear in front of the grand jury,” he said. “And the same went for all of the women were found inside the club. The King of the Road was an outlier because there were only a few other defendants in the case. It wasn’t the Hankish case, but the operation was thorough.”

Just four months later, a Clarksburg jury found Truglio guilty of 17 of the 25 charges against him, and Ebright, Hess, and Pavilack were found guilty on all counts and sentenced each to five years in prison with a $10,000 fine. The charges against Demko were dismissed in exchange for his cooperation.

Truglio was sentenced to 25 years in federal prison, and he was fined $50,000. In addition, the jury ruled that all property in connection with the Dallas Pike establishment be forfeited. Truglio’s ex-wife, however, sued the United States government in August 1983, claiming she and her former husband made a deal on the Triadelphia property.

Elizabeth Ann Truglio filed the civil suit in Ohio County Circuit Court contending the parcel was leased to the King of Road until the forfeiture and was the “corpus” of a trust established for the couple’s children, Doris, Charles, and Joseph Jr. The couple were divorced in 1980, and the ex-wife insisted the agreement with Truglio was in lieu of child support.

Mrs. Truglio lost the civil suit, but Joey Jr., Truglio’s 57-year-old son, still insists the Justice Department still owes his family.

“I was always told that my mother and father made a deal on the Dallas Pike property after they got divorced,” the son explained. “It was supposed to be our trust fund or something like that, but when the raid took place, we got nothing, and I’ve seen that property change hands a number of times in the last 40 years.

“I know what my father was convicted of, but I always say these days that he’s innocent because the same stuff is still happening today and some of it has been legal so the state can make the money. Prostitution is still illegal, I know, but the gambling side of things is all legal now, and it’s all over the place,” he said. “Just seems unfair, and I still think the government owes us something because it seems like they acted greedy. People just seem to amaze me when it comes to their love of money.”

Joey Jr., a current resident of the Weirton area, knows his father was sent to the federal prison in Springfield, Mo., and he knows that’s where his daddy died.

“My last memory of my dad was when me and my stepmom, Helga (Truglio), took him to the Pittsburgh airport so he could fly to the federal prison in Missouri,” the son recalled. “When we were dropping him off at the entrance, I remember him turning back and saying, ‘Should I fly to Germany and get a disguise?’ At the time, I really didn’t know why he would say that.

“It wasn’t too long after my dad went to prison that he passed away,” Joey Jr. remembered. “Like I said, I know what he did, and I know he went to prison for what he did. But I still miss my dad.”

The Series:

(Author’s Note: Each week I’ll be sharing a link to one of the chapters of my first “Wheeling Mob” series I wrote while serving as the founding editor-in-chief of Weelunk, a digital media site now owned and operated by Wheeling Heritage, a non-profit organization that promotes the history and heritage of the city of Wheeling.)