(Publisher’s Note: The 12-part series, “The Children of Wheeling’s Mob Era,” will be re-published each evening over the next two weeks so those who missed some or all of the chapters will have another chance to read it. A collection of Steve Novotney’s mob stories over the years will be released in book form this summer.)

1

Betty and a Bomb

It was frigid that Friday morning on January 17, 1964. Snow was on the ground from the night before, and it was as quiet outside as winter could be 60 years ago along Richland Avenue in Warwood.

Until it wasn’t.

Wheeling police officers and firefighters responded to a home near the corner of Fourth and Richland after reports of an explosion were called in by the neighbors. A 1964 four-door Studebaker was detonated at about 10:30 a.m. and windows were shattered, debris was scattered, the working-class neighborhood was understandably stunned, and a 32-year-old man named Paul Hankish screamed for help after most of his legs were blown away by the dynamite blast.

According to the police report, a man named Harold Bauers rushed to the scene where the car’s carcass continued to belch smoke and flames to find Hankish covered in blood but still conscious and lucid.

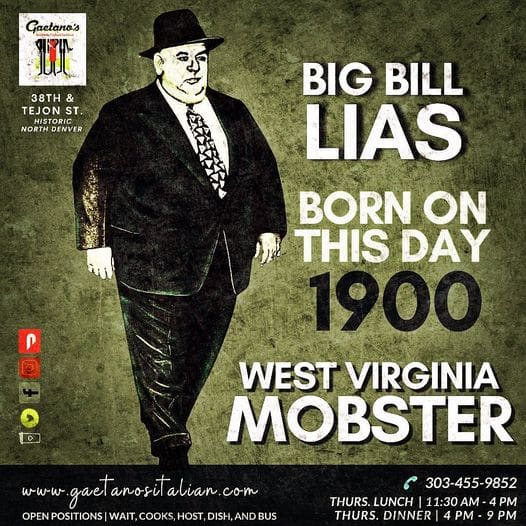

Bauers told police he heard Hankish say, “That f*cking Bill Lias,” before he ran to call for help.

Later the same day, according to the officers who interviewed him at the old Wheeling Hospital in North Wheeling, Hankish insisted, “F*ck that fat pig.” That’s where he would stop, though. Every time.

Wheeling firefighters found Hankish still seated in his vehicle conscious, lucid, and screaming. “Get me out of here! Get me out of here before I burn to death! Hurry! I’m on fire here!”

A shy 12-year-old Italian girl lived with her parents just a few homes up the street in a first-floor apartment. She remembers that morning. She heard it, she felt it, and 60 years later, it’s her preference to offer her memories without using her real name.

Why? Well, because those seven sticks of dynamite frightened “Betty” forever.

“There was a side lot next to the house where my family lived then, and then there was a house and another lot. Next to that was where the Hankish house was, so there were three lots between our apartment and where the explosion took place,” she explained. “It was Paul and his first wife, Pat, and they had their daughter (Rose) and the little boy (Christopher Paul), and they needed babysitters because Mrs. Hankish worked. One of my friends was one of the babysitters and I’d go to their house sometimes.

“My friend invited us up when she got bored with their two kids, and we would play with them outside on those afternoons,” Betty recalled. “The kids were very nice children, especially the daughter. I remember her as a very sweet little girl.”

Known Offender

“Hankish was bad from the beginning. That’s why he went to prison as many times as he did. But he did the time, got out, and went right back to using an impressive criminal mind.”

U.S. Attorney William Kolibash

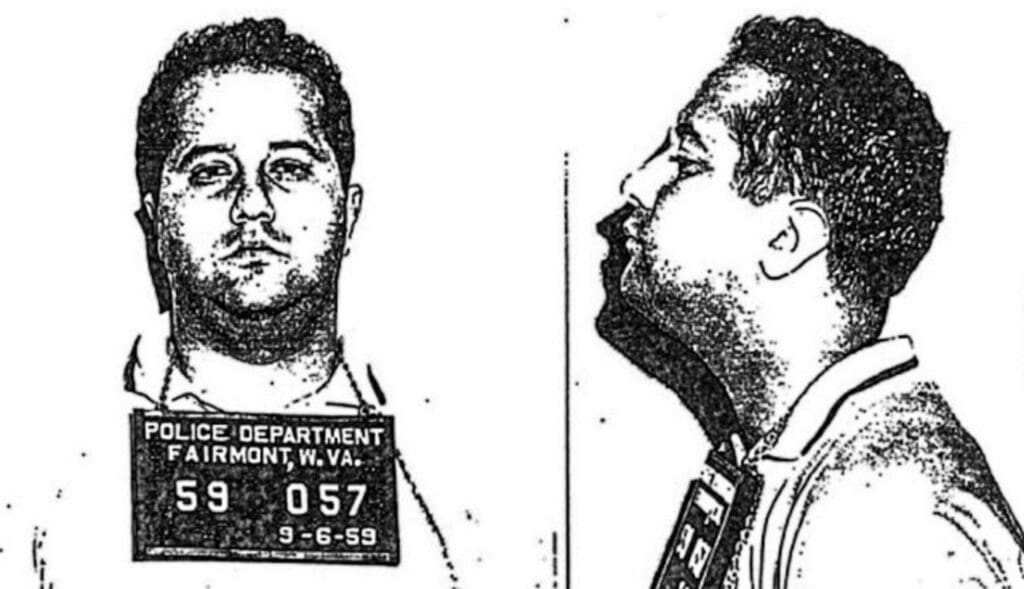

Hankish already had served several jail sentences by the time he and his family moved to Richland Avenue in the early 1960s, and he had been released from the West Virginia Penitentiary in September 1963. He worked legitimately in the jewelry and automobile businesses, but, according to newspaper reports, Hankish quickly returned to hustling hard around the Wheeling area once he was a free man.

During his colorful career, Hankish fenced stolen goods from trailer hijack jobs, owned poker machines and ran game boards in bars, and operated as many as 24 full-blown brothels in Center and South Wheeling. In the early 1960s, Hankish was recruiting new crew members, too, some of whom had previously worked similar rackets for Lias.

They made their daily rounds, collected cash, paid visits to “past due” situations, and addressed liars and cheaters with mob muscle.

“I can remember one day when we decided to go up to the Hankish house to visit our friend and the parents were there. They were both very cordial to us,” Betty recalled. “But I remember a couple of Mr. Hankish’s men came in the house, too. They were dressed very nice in their suits, and no one said anything, but we took the children outside to play.

“I looked back at the gentlemen when we were leaving and I saw them take off their suit jackets, and both of them were wearing holsters with pistols. The holsters were brown. The guns were black. I think the handles on the guns were brown. It was something straight out of “The Untouchable,” I tell you. I was old enough to know the difference between what I saw on TV and what I saw in real life, and that scared me.”

Betty ran home. Betty told her parents about the guys with the guns. Betty was never allowed to visit the Hankish children ever again.

“‘No, no, no. That’s it.’ That’s what my mom said to me, so, that took care of that,” she recalled. “I never went close to the Hankish house again. Never. I don’t even think anyone really knew what Paul Hankish did for a living, but I think the neighbors suspected something.

“I believe everyone suspected something, but everyone was too afraid to say a word. That’s how it was back then. If it didn’t concern you, you left it alone for your own good.”

BOOM!

“Paul Hankish was a young thug; that’s what he was before the bombing, and that’s why someone tried to kill him. He was moving around doing a lot of things, and someone didn’t like it.”

Former FBI Agent Tom Burgoyne

The hood of Hankish’s Studebaker ended up on the roof of the house across Warwood’s Richland Avenue, and the majority of his legs were “mangled” and ripped from his torso and discovered under the driver’s side seat. He was “cut up with a quite a number of lacerations on his face,” according to then Fire Chief William McFadden.

McFadden also told Wheeling newspaper journalist Al Molnar, “I don’t think he will make it.”

Somehow, though, the gangster didn’t bleed to death. Somehow, Paul Hankish survived. The headline in the Wheeling News-Register the day of the explosion read, “Hankish Critically Injured in Assassination Attempt”.

Molnar described the attack as “gangland-style,” and he reported that wife Pat told authorities she “knew of no trouble he was having with anyone.” Molnar included in the article that Hankish had been “associated with underworld activities since the mid-1950s.”

Young Betty knew that to be true, but she wasn’t allowed outside to see for herself.

“I was in my parents’ apartment, and it was still in the morning after the school buses because I didn’t go to school that Friday,” she recounted. “I heard the bomb go off. I felt it. It shook the whole house. It rocked the whole neighborhood. We didn’t lose any windows, but the houses across the street did. I remember feeling that explosion for sure.

“We lived in the apartment on the first level of the house, and the owners of the house lived upstairs. They were good friends with my parents and they were great to me, too. I know my mother and the lady from upstairs went outside and at first you could get pretty close but then the policemen were keeping people pretty far away from the car,” Betty said. “There were detectives in the neighborhoods for days looking for who knows what.”

Infamous Status

“That bombing case will never have an ending, but that never mattered anyway. Hankish became a folk hero because he survived that bombing. He became a superhero.”

FBI Agent Tom Burgoyne

The charred Studebaker had been towed away by the time Betty was allowed to go back outside, and she doesn’t remember burn marks on the street. The neighborhood kids never found anything close to a car part the authorities might have missed, and Betty doesn’t remember an odor either.

The neighborhood kids compared notes about what they heard and saw, and they wondered why, too. Why would someone’s automobile explode just because they tried to start the engine?

“I think we all just couldn’t believe how a man survives that explosion based on what we heard and felt,” she said. “It was from head to toe, it shook me and I definitely wasn’t allowed near the Hankish house after that, and trust me, we didn’t even get close. We just wanted to stay away from it all. Our parents told us to leave it alone, and we did.”

“I know the FBI people showed up the next day and they were walking around trying to talk with as many people as possible. From what I remember, no one said they saw a thing. No one seemed to know how that dynamite got under that Studebaker. Or no one was saying anything anyway.”

Five days after the blast, the newspaper’s Al Molnar reported Hankish was in “good spirits,” but was no longer supplying law enforcement with any information that could help solve the case. Journalist Roger Wood from The Intelligencer then reported two days later that Hankish had not offered names to the police, according to attorney Robert Yahn, and that the gangster is not sure who would try to kill him.

Hankish changed his tune.

“I’m sure people got to him and told not to make the waves with Lias because of what he had coming to him after surviving the bombing,” explained William Kolibash, the U.S. Attorney who finally sent finally Hankish to federal prison in 1990. “I can tell you it was my experience with the guy that he loved when people thought he was invincible because of the bombing, and because he was able to get away with so much.

“Hankish may have gone to prison a few times during his lifetime, but he didn’t spend nearly as much time behind bars as he could have. But he was smart. He got away with much more than he got caught doing,” he said. “Until the end, of course.”

Betty doesn’t remember when Hankish returned to his Richland Avenue house later in the springtime of 1964, and she doesn’t believe she and her friends ever chatted about the bombing or about those holstered guns. They did recognize the line that was established by their parents once playing outside was an everyday activity.

“That part of Richland Avenue was forever cut off for me and my friends. That’s how the parents handled it, and my family lived there for a lot more years,” she said. “I did see Mrs. Hankish going in and out of the house sometimes, but I never saw him and I never did see the little boy and little girl again. The Hankishes moved from there before my family did, but no one paid attention to that either.

“It was like we all just forgot about them for our own good because we were too scared to talk about any of it,” Betty added. “But Mr. Hankish was in the news a lot through the years like he was some big celebrity in town. And I guess he was that, too.”

The Series:

(Author’s Note: Each week I’ll be sharing a link to one of the chapters of my first “Wheeling Mob” series I wrote while serving as the founding editor-in-chief of Weelunk, a digital media site now owned and operated by Wheeling Heritage, a non-profit organization that promotes the history and heritage of the city of Wheeling.)

I am so interested in these stories regarding Wheeling and the mob days. Is there a book I can purchase.

I will be putting these chapters together in a book form sometime in 2025. Thank you for asking. Much more to come. – steve

Great 4-parter Steve

Will buy the book

Far from over! Much more to come. Thank you, Ross.

Absolutely love that your putting this together and out there for people to know about and be recorded, it is the history of Wheeling and so many people have no idea that it is. Thanks for your efforts and time in doing all this. Any idea when the book will be available and where it can be purchased at? I’m sure many inquiring minds would like to know. Thanks again Steve!

I am working on it now. Ty!