(Publisher’s Note: The 12-part series, “The Children of Wheeling’s Mob Era,” will be re-published each evening over the next two weeks so those who missed some or all of the chapters will have another chance to read it. A collection of Steve Novotney’s mob stories over the years will be released in book form this summer.)

WARNING: Profane language appears in the following article.

10

Dickie and The Mahoff

His name was Gerry Cooney and he was a pro boxer out of Long Island, New York, who became known as one of the hardest-hitting heavyweight fighters in all the world. He was blue collar and he was Irish Catholic, and Cooney recorded 55 victories and three defeats as an amateur Gold Glove champ through the early to mid-1970s.

Cooney was a big man, too, standing at 6-foot-6, and once he turned pro in 1977, he attracted the attention of boxing’s super promoter Don King. Soon after Cooney defeated Ken Norton in 1981 by way of knockout only 54 seconds into the first round, and he then waited more than a year for his chance at the champ, Larry Holmes. And finally, on June 11, 1982, King delivered and labeled Cooey the “Great White Hope.”

The bout was scheduled for 15 rounds at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, and the purse was $10,000,000. Holmes knocked down Cooney in the second round, but the challenger got up and survived until he was defeated by technical knockout in the 13th. Cooney had bloodied Holmes and swelled his eyes, but at the end of the evening, the champ was still the champ.

Although “Gentleman” George Cooney was a southpaw, he fought Holmes as a right-hander because many boxing experts believed lefties had too many open targets for those fighting in an orthodox style. That’s what Dick Flanagan’s father told his son, too, but “Dickie” was a tough-kid scrapper from Rose Hill in Bellaire, Ohio, and he wanted to become the sport’s next great Irish boxer.

“I knew a few of the guys who were involved with local boxing back when I was around 16, and I wanted to be a boxer when I was young. But my dad didn’t think it was good idea because I’m left-handed,” Flanagan said. “I thought I was tougher than that, so I didn’t give a shit what my old man thought back then. I knew it all back then, ya know?

“So, I heard about a place on Wheeling Island where they boxed, and there was a guy named ‘Big Joe’ who was training guys there. Turned out, ‘Big Joe’ was Joe Mucheck, one of Paul Hankish’s inner circle guys, and he took a liking to me,” he said. “I do remember when my dad found out I was going to the gym on Wheeling Island, and when I got home he said, ‘You wanna be a tough guy?’ and then he put a whipping on me. That was the end of my boxing career.”

Instead, Flanagan went to work for “Big Joe” as security in a few bars in and around Wheeling, and those positions eventually attracted attention from the man at the top. Most people, back then and especially today, knew the mob boss by his formal name, Paul Nathanial Hankish, but Mucheck introduced the kingpin to Flanagan as the “Big Mahoff.”

It was a term, Flanagan was told back then, that was most used on the streets of Philadelphia when referring to an important person, and it stuck with him then and through the years.

“Back then, I was bouncing in the bars when I first came home from my four years in the Navy, and eventually I ended up with the bricklayers as an apprentice. But I went to work one time in one of those blast furnaces in a steel mill, and I knew then I didn’t want to do that shit,” he insisted. “So, I went to the laborers local and that was OK because I started learning how to be the business agent.

“But ‘Big Joe’ came up to me one night when I was bouncing for him and he told me it looked like I knew what I was doing and he told me that’s why I was working at Hankish’s bar,” Flanagan remembered. “And then one day, ‘Big Joe’ told me the Mahoff needed a driver. That’s what the guys in the inner circle used to call Paul – the Mahoff – and I was told to call him that, too.”

In All Directions

When most people in the Upper Ohio Valley hear the name Dick “Dickie” Flanagan, they immediately relate it to the hard-core member of law enforcement who retired as the chief of the Bellaire Police Department about two years after spending more than 30 years fighting crime in several communities in East Ohio. But 40 years ago, after he was graduated from Bellaire St. John’s in 1979, he worked odd jobs before enlisting for four years in the U.S. Navy.

“The military didn’t stick, though,” he admitted. “I decided it wasn’t for me, and I came home, but back in the 1980s was when the good jobs were starting to dry up and you had to know someone. So, I tried the unions, and then ‘Big Joe’ told me about the Mahoff, and he set it up.

“I met with Paul and we bullshitted for a bit, and I think that’s when I realized how intelligent the man was. I never thought for a minute that he was dumb or stupid, but we talked for a while and I could tell he was articulate when discussing his business and how he went about it,” Flanagan said. “He told me what he thought I needed to know.”

Hankish had been in need of a driver after losing his legs in an explosion in January 1964. The incident was deemed an assassination attempt and “Big Bill” Lias was questioned by authorities, but no arrests have ever been made in the case.

“When the Mahoff would call, he would tell me certain things that meant nothing about what he wanted because he had this code he’d tell you about. If he said we were going for a ride, that meant we were going somewhere like Pittsburgh or Steubenville. Before me, there was Dave Talbert, but the Mahoff told ‘Big Joe’ it was time for a change. That was me. I was the change.

“Other guys had nicknames, too, like Paul’s brother Phillip as ‘Sunshine’ and Mucheck was ‘Big Joe.’ And, yeah, Paul was the ‘Mahoff’ because he was the boss. I mean, you didn’t dare refer to him as ‘No Legs’, that’s for sure. That never turned out good for the person who would, I can tell you that,” Flanagan said. You never got Paul’s nickname wrong. He was the ‘Big Mahoff and everyone knew it.

“It was that, or you called him ‘Boss’,” he said. “And he was the boss, that was for sure.”

During his brief tenure connected to the Wheeling’s underworld, Flanagan quickly developed an understanding for how organized crime worked.

“If you owed, you owed and you better pay. It can’t get any easier to understand, and if you didn’t pay, then you got what was coming to ya,” he recalled. “But I also know of some incidences when guys would go in the bars and gamble away their whole paychecks and their wives would come in. That would get back to Paul and that’s when Paul would send someone with an envelope, and there was money in there.

“They’d give the money to the wife and tell the husband to knock off the bullshit and that they’re no longer welcome there,” he said. “He told them to take care of their families and to stay away. The guys who didn’t listen to him sure wished they would have, I’ll tell you that.”

The driver and the “Big Mahoff” got to know each other, too, and while there exist very few facts on file about the friendships owned by the mob boss, Flanagan has memories of moments when the two would exchange barbs back and forth.

“We did get familiar enough with each other that we started fucking with each other and I remember ‘Big Joe’ asking me if I was crazy for messing with the Mahoff so much. I told him to relax because we had that back-and-forth and that it was funny,” he said. “Ya know, when you drove for the guy, he never told you where you were going. It was like he was protecting you or something.

“He never said we were driving to Cannonsburg or Washington; he’d just point and off we went,” he recalled. “Other times, we’d stay local, and I always had to have at least three rolls of quarters because Paul always used the payphones. He didn’t take any chances.”

Bill Kolibash was the U.S. Attorney when a federal grand jury indicted Hankish and several others 218 times in early October 1989, and he remembers the payphones and the quarters, too.

“As long as we investigated Hankish, we never found any proof that he had an office of any kind, and that’s why we expected to find what we needed during the raids on his two primary locations during the mid to late 1980s,” he explained. “Paul Hankish was transient when he was working. That’s why we’ve always heard the stories about the rolls of quarters that he always had because he was using payphones when he needed to make calls.

“He would use different payphones, too, but they were always the phone booths with the closing doors,” recalled Kolibash, the U.S. Attorney from 1982-93 after joining the office as an assistant in 1973. “We couldn’t listen to his calls because he used payphones, but we could get the numbers he was calling. We didn’t get much from knowing the numbers, but it’s an example of the kind of resources we had back then.”

To Flanagan, though, the use of payphones was just another example of how organized crime remained unaccountable for decades in the Wheeling area. Lias reigned supreme as the boss over gambling, racketeering, and prostitution for a little more than 30 years before Hankish took over following his passing in June 1970.

The Internal Revenue Service may have seized Wheeling Downs away from Lias for back taxes in 1955, but “Big Bill” remained relatively unscathed when it came to the laws and their enforcement. Hankish, however, had a rap sheet that dated back to the late 1959s.

“Listen, the Mahoff might have been a no-good criminal, but if he liked you, he liked you, and I think he had some morals and scruples to him. That’s why he didn’t like to involve the kids in anything he did and why he had mercy on so many people who owed him big. And listen, when a truck with turkeys or hams or diapers got hijacked, he made sure he took care of the unwed mothers at the YWCA.

“But if you crossed him, you had problems,” Flanagan said. “Big problems.”

Beyond the Headlines

There were spot sheets in high schools, cocaine in night clubs, civic leaders employing professional gamblers, green doors and red lights glaring in Center and South Wheeling, and even a store filled with stolen merchandise with snipped labels and reduced price tags.

While some referred to the Wheeling area as the “wild, wild Gateway to the West” because of the Suspension Bridge spanning the front channel of the Ohio River and the all-year open season on what many deemed the “Wheeling Feeling,” others – like Kolibash and his task force on organized crime – were determined to end the lawfulness pushed upon by people involved with the Hankish organization.

But what about Flanagan? Back in the 1980s, he was a kid searching for his place in the professional world who still insists he was never compensated by his “Big Mahoff” for the driving services rendered.

“As far as what our evidence showed, Dick Flanagan wasn’t breaking any laws by just driving Hankish where he needed to go, and if he didn’t get paid anything for being his driver, that doesn’t surprise me because we learned he paid people through doing them favors or by giving them some of the stolen merchandise that came in all of the time,” said Kolibash, whose book, “Justice Never Rests” was released Tuesday. “That’s why people really liked Ron’s Value Center. There was new stuff in those cases all the time, and it was cheap.

“Plus, Talbert and Flanagan, they loved hanging out with those mob guys because it gave them prestige, I guess, and no one would mess with them,” the former federal prosecutor said. “People could turn (Hankish) down, too, and that didn’t seem to cause problems. But once you owed him, you owed him forever.”

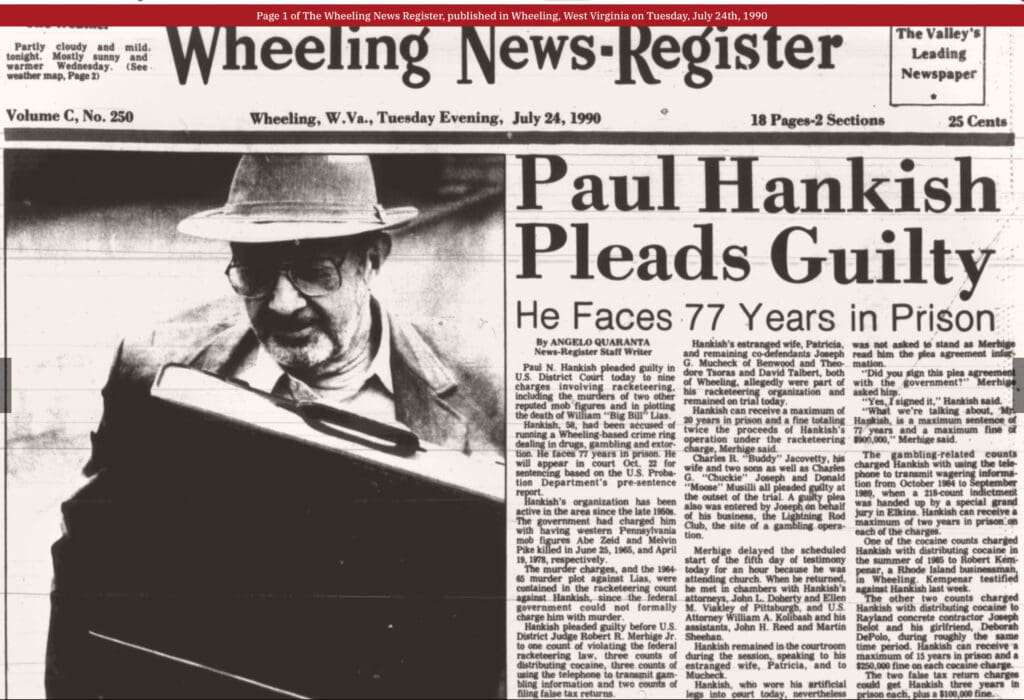

Until that is, Kolibash collapsed the rackets, the rings, and the houses of prostitution after a four-year investigation led to the prosector’s broadest RICO case of his career. The federal grand jury returned 218 indictments against 11 individuals, including 90 charges against Hankish alone. Two members of his gang, in fact, testified against him – Ron Asher told Judge Robert Merhige he was hired to kill, and Clark explained the organization’s drug trafficking business.

But it wasn’t until the mob boss was informed during a break in his bench trial that his estranged wife, Patricia, was Kolibash’s next target when an ultimate decision was made. And Flanagan was present to hear it.

“I had driven Paul to the courthouse, and we were going up the elevator when his attorney told him that the government was going to talk about all of the drugs and that they were going to connect that stuff to his wife. That’s when Paul told him he needed to go cut him a deal. He said he was done. He wanted to protect his wife,” Flanagan said. “At first, after the attorney told him, he was quiet. And then he said, ‘That’s it. I’m done.

“He told his attorney he wasn’t giving up no one either. He said he was pleading guilty to whatever so it could be over and Patty would be OK,” he said. “But they had to leave Patty alone.”

With the decision made and the message on its way to Kolibash and his team, Flanagan was directed by his boss to one more destination.

“After the Mahoff told his attorney to make the deal, he looked at me and told me we were going to lunch. So, we went to Ernie’s Esquire again,” he said. “We went in and sat in the same booth he always sat in, and when the waitress asked Paul how he was, he said he was just fine. Now, he knew he was going to prison for a long time, but at that moment, he said he was OK. And I think he really was OK.

“He told me to order whatever I wanted so I ordered the blackened swordfish because I’d never had it before and because it was the cheapest thing on the menu, but I knew he was going away. I knew it back in the elevator, but I just think he realized he wasn’t getting away with everything forever. I think he knew it was going to catch up with him someday … and that was the day.”

The food came and the two talked. There were no attorneys, no enforcers like Jesse Anderson or Jimmy Griffin, and no other henchmen either. “Busy talk” was how it was explained by the driver, and, at one point, Flanagan’s future became a topic.

“When we were sitting there, out of nowhere he said, ‘What do you think you’ll do next? Because you can’t make a living being a bouncer at a bar’. He told me the only way to make any money from a bar was to own the bar, and he was right, of course,” Flanagan said. “That’s when I told him I thought I would go into law enforcement.

“Paul told me that if I was going to be a cop, I’d better be a good cop. He said that anyone could be a fuckin’ dirty cop, and he was looking at me dead in the eyes, too,” he remembered. “I thought he might have said I was crazy for thinking about being a cop with everything considered, but he gave me that advice instead.”

Hankish’s wife was the only individual acquitted in the July 1990 trial, the “Big Mahoff” pleaded guilty to nine charges and was sentenced to 33 years in prison, and he passed away in the federal prison in Petersburg, Va., at the age of 66 from kidney failure on May 11, 1998.

And Dickie Flanagan took Hankish’s advice.

He began his career in Bridgeport and worked in Martins Ferry, too, but it was the “Great American Town” of Bellaire that motivated him the most, especially once Flanagan’s concentration focused on drug trafficking. That’s why he helped start the Belmont County Drug Task Force, and was deputized by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration and by the US Alcohol Tobacco & Firearms.

Flanagan also served with the South Eastern Narcotics Task Force and the U.S. Marshals Mountain Fugitive Task Force, but, without any fanfare, Flanagan retired unannounced during a Bellaire Council meeting on March 16, 2023.

“I didn’t want a cake or anything like that, trust me. I had just made the decision that the time had come; that I had enough,” Flanagan added. “And people can say whatever they want, I know I did my thing, I did some good, and I did it the right way, and I had a good, run, too.

“I guess I did take the Mahoff’s advice.”

The Series:

(Author’s Note: Each week I’ll be sharing a link to one of the chapters of my first “Wheeling Mob” series I wrote while serving as the founding editor-in-chief of Weelunk, a digital media site now owned and operated by Wheeling Heritage, a non-profit organization that promotes the history and heritage of the city of Wheeling.)