(Publisher’s Note: The 12-part series, “The Children of Wheeling’s Mob Era,” will be re-published each evening over the next two weeks so those who missed some or all of the chapters will have another chance to read it. A collection of Steve Novotney’s mob stories over the years will be released in book form this summer.)

6

The Cocaine Courier

Some nights there were parts of downtown Wheeling that glowed like pinball machines from all the bumper-to-bumper brake lights and storefront neons, and on Saturday nights, Main Street was lined with motor coaches in town for the Jamboree.

Those Canadian fans came to town week after week to see country singers like Conway Twitty and Billy “Crash” Craddock, and they joined the locals in the bars and restaurants throughout downtown, too. Near the Capitol Theatre, Fabulous Fannies, the Bridge Bar, the Ballroom, and the San Antone tavern swapped partiers on weekend evenings, and the sidewalks on 12th Street were crowded with men and women from the Club Diamond, Ernie’s Cork & Bottle, the Club Tower, and The Office.

A number of establishments lined lower Market to 16th, as well, and The Sportsman and the back-alley, three-story Tin Pan Alley usually drew dense crowds.

There was a harmonious hum to those areas, too, with the purring engines and echoes from live music adding to the “Wheeling Feeling” atmosphere. The disco dance clubs blinked with perpetual strobes, but the bars were dark with their same-seat regulars, cleavage pouring the drinks, and the “secret” back-room poker games everyone knew about. Pilsners were chilled for daily draft specials, the only TV had the game on, ashtrays were emptied pretty often, and most “joints” didn’t need windows or clocks.

There were plenty of popular places outside of downtown, too, like the Pirates Cove (or Palace Disco depending on the year) in Center Wheeling and the Flamingo in Benwood, and a man we’ll refer to as “Courier” paid visits to them all.

“There were a lot of bars. They were everywhere, and everyone wanted cocaine,” said the former – and anonymous – coke dealer. “The Tin Pan, Merrymint, the Whistle Stop, the Swing Club, Mac’s on Washington Avenue, the Eagle Inn … it really went on and on on. There’s times when I can’t believe it all happened back then and in a lot of ways, it doesn’t seem real now. Maybe because I made it out alive.

“I didn’t do cold calls. I knew who I was meeting at each of those places. We’d just walk into the restroom if we had to, or I’d go in and place it on the shelf or wherever and go back out and give them the nod,” he said. “It went down how it had to go down, I guess, because you had to roll with whatever if you wanted to make that kind of money. There was a lot of money.”

“Space Invaders” and “Pac Man” were the hits at the arcade, Nintendo and someone named “Super Mario” were introduced in the 1980s, a contraption called a “personal computer” was suddenly on sale at Radio Shack, and U.S. President Ronald Reagan had Wall Street believing in something called “trickle-down economics”.

His wife, Nancy, was the First Lady who adopted the federal government’s war on drugs, and she launched the national – and notorious – “Just Say No” campaign.

Courier’s customers, though, weren’t listening.

“Not only was I selling coke, but I sold at least a pound of weed a week, plus there were quaaludes, speeders (amphetamine), and ‘Black Beauties,’ (biphetamine), too. The speeders were really popular with women back then because they told me they let them get done with the housework really fast.

“I know some people bought them off of me and drove straight to Dallas Pike to sell them to the truckers,” he claimed. “I didn’t care because I didn’t want to go up there and get in the middle of all that. Besides, I couldn’t keep them in stock, really, but that didn’t stop people from bugging me all the time for those pills. A lot of doctors were prescribing them back in those days, too, but I had them for a better price.”

Bill Kolibash joined the U.S. Attorney’s Office in 1973 as an assistant, and Reagan appointed him to the federal prosecutor’s position a decade later. Not only did he launch his investigation into Paul Hankish and his web of organized crime at the same time he and his wife, Rita, were raising their three children in Wheeling, but the Kolibash couple went out on the town from time to time.

“People were very social in Wheeling back then, and a lot of it was happening downtown with all the restaurants and the bars. There sure were a lot of restaurants,” recalled Kolibash, who will release his book, “Murder Never Rests” later this month. “And Paul Hankish was everywhere, too. He didn’t hide, and neither did his guys, and everyone had their favorite places. Hankish welcomed the attention. He loved it.

“Once the FBI gained jurisdiction over cocaine in the early ‘80s, we knew how much cocaine was out there because of the investigation, and it was widespread, that’s for sure. There was a lot of cocaine in Wheeling.”

In Plain Sight

He carried a satchel and played many parts. A salesman. The next patient. A family member. Whatever got him past the secretaries and receptionists at the doctors or dentists, in office buildings, and even inside courthouses.

He wore slacks, a jacket, and a tie during his daytime rounds. Courier was a businessman and his product was in his “man bag,” after all, and his headquarters was his home in Moundsville.

“During the day I’d stop at a couple of banks in downtown Wheeling, a couple of office buildings and businesses, too. That’s after I did what I did down in Moundsville at all of those law offices, and on the way up to Wheeling. There were a lot of customers everywhere,” Courier said. “If I went over to Martins Ferry, I would go to a dentist’s office, but it wasn’t so much for him but for his girlfriend. She really enjoyed it.

“He was really paranoid about it because he knew he’d go down if anyone knew, but he always had the money ready,” he said. “The demand back in the ‘80s was higher than anything else I’d seen.”

So much so, Courier explained, he noticed changes in behavior with law enforcement.

“It got hot sometimes. I’d see twice the cruisers on the streets, and sometimes Wheeling had a cop walking. You knew they were on to something or looking for something. Or maybe someone. I just knew I didn’t want it to be me.

“I changed things up. Went the other way. Mixed up the routine.”

So, when that was the case, he instructed his customers to visit his house in Moundsville instead of making his usual rounds. But not one by one.

“I would have a lot of the people come to my house, and I would tell them all to come at the same time so it looked like I was having a party. I didn’t want everyone coming in and out because that was a sign I knew the cops would notice,” Courier said. “They would all come pouring in at once, we’d take care of business, hang out a while and share a little, and then everyone would leave. It was far less suspicious that way instead of people coming and going.

“And I would make house calls for some of my best customers. They’d put the kids to bed and then welcome me into their homes. The coke was more popular with the men, and the women loved the quaaludes. They told me it made their sex life better, and I’ve always believed that if it worked for them, it worked for them. People were just trying to have a good time.”

Day or night, rain or shine, no matter where, and four seasons a year, cocaine was the most popular product.

“People mostly bought grams; sometimes a couple of grams at a time, and there were the eight balls, too. That’s when someone was having a party or someone was trying to make a buck by selling some,” the dealer explained. “People bought weed back then, too, but it wasn’t close to what we have these days. You had to smoke a lot of it to get high back then. And there were pills, too, but coke was by far the most popular.

“Eight balls were $250 back then, and a gram was $100. I used little bottles usually but if the pharmacy didn’t have them, I would wrap the coke in magazine paper. That was the best paper because it didn’t absorb,” he recalled. “I’d get the baby (laxative) at the pharmacy, too. Never too much to raise suspicious, though.”

Let The Good Times Roll

His “guy” was a man named Donnie Clark, the son of a car dealership owner in Wheeling who ended up snitching to the feds in exchange for the witness protection program for he and his wife.

Clark delivered the narcotic in rock form, and in the beginning, the supplier had to teach Courier how to cut his coke. The supplier visited often, too, and sometimes just to escape the non-stop hustle on the streets of Wheeling.

“When I first got started, I was told that if you got cocaine that was higher than 35 percent, it would kill you. So, when he would give me a rock each time, I would cut it with the Mannitol, and that would up my take. That’s what Donnie Clark taught me,” Courier explained.

“Donnie was the main guy I got it off of anyway, and he treated me like gold, but when he was taken down, I was asked why they didn’t arrest me, too. I knew I had only gone to Donnie’s house once that whole time, so that was a good thing. And Donnie always came to my house to get away from everything in Wheeling,” he said. “And he always said we were real friends and not just ‘friends’.

“No wonder … I did make the man a lot of cash.”

Courier made lots of money, too, and he laundered his take by paying cash for home improvement projects, fine furniture, cool cars, and other such luxuries he’d always dreamed of owning.

“My God, did I make a lot,” Courier said. “I put new windows in my house. I put siding on my house. I bought new furniture, a beautiful bedroom, and brand-new vehicles. Hell, I even bought a boat with all of that money. And I paid cash for everything.

“It was all about having a good time because I always had the money to have a good time. It didn’t matter what time of year it was either. People wanted cocaine all, of, the, time. They loved it, and I suspect people still do these days.”

That boat, by the way, came in handy when the heat got hot.

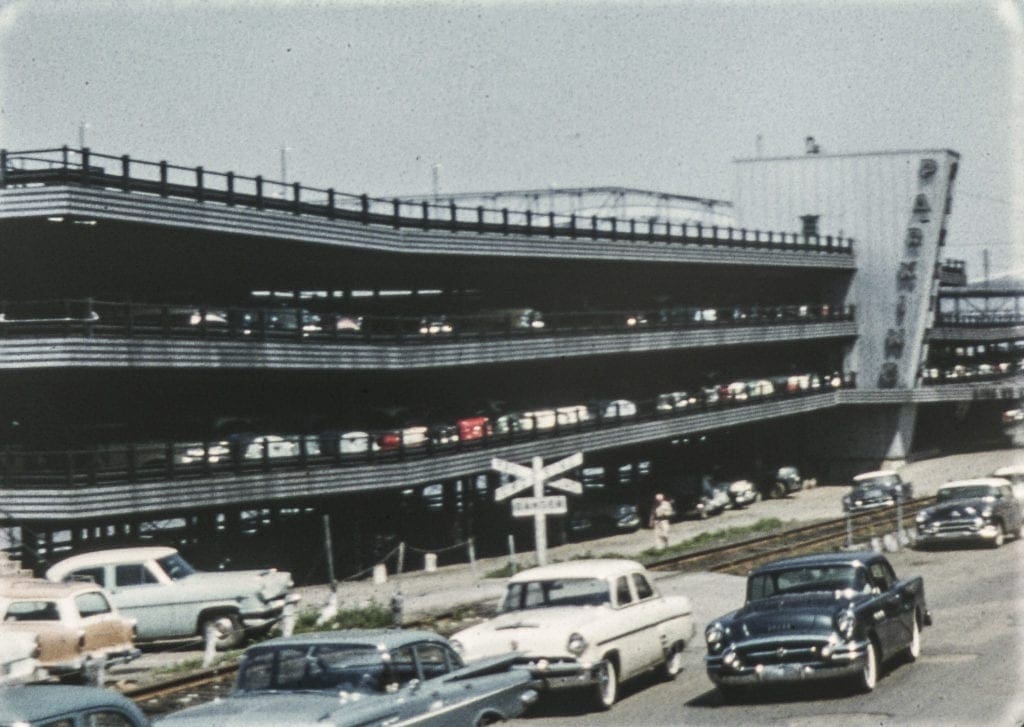

“I bought that boat for two reasons – to party, and to avoid the cops,” Courier revealed. “It was for pleasure, but the highway traffic was getting too risky. So, yeah, I bought a boat to take cocaine up and down the river, and I’d have people meet me up by the Wharf Garage or even down by Fish Creek.

“I had different stops where I’d deliver. A bunch of years later, I told a former police officer how I used the boat and he told me they had never thought of drugs on the river. Not back then. I had to be smart because you never know who’s going to get busted and say something. But when Donnie was taken in, I guess he didn’t sell me out because no one ever came looking for me.”

Before Clark and his wife vanished into Witness Protection, he was interviewed by Kolibash and the late Tom Burgoyne of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The investigators heard about pickups and deliveries, the names of who did what and where, and in some cases, Clark connected the dots on Hankish’s trafficking network.

“Donnie was a guy in his 40s that we knew was working for Hankish when it came to the drugs the mob was bringing into the area,” Kolibash explained. “And it was surprising to us at first because organized crime had a history of staying out of the drug business because it was too risky. Once we picked him up and started to interview him, Donnie realized what he was facing as far as prison time. That’s when he made the decision to cooperate with us.

“He told us how he would get the cocaine, how it was coming into Wheeling, and how it was all connected to Hankish and his organization,” he said. “He gave us everything we needed so, instead of prison, we offered him the Witness Protection Program and he took it.

“They went away and I have no idea where they went. Not even the U.S. Attorney gets that information, but I do believe he came back after Hankish was put away.”

High on His Own Supply

He shakes his head when he tells his tales about waking up in strange places, and Courier admits to losing time while high on cocaine, smoking marijuana, and drinking mixed drinks one after another after another.

Whether he was in the middle of the mayhem in downtown Wheeling, cruising the National Road stretch with the Swing Club, Woodsie’s, and the Under Glass at Howard Johnson’s, or checking the scene at the Glassworks Lounge inside Wilson Lodge, he was high, too. Courier was a good tipper and that’s why he was taken care of very well along his sales routes, but the time arrived when he was forced to make decisions in favor of freedom and survival.

“I was in on it from 1977 through a lot of ‘80s, and I got out of it because I got addicted to it. I made the biggest mistake. I got hooked. Bad. I loved that stuff and how it made me feel. I can still remember it, but I fought it and hated every second of it.

“Matter of fact, when I quit, I still had an eight ball in the refrigerator and it stayed in the there for a while as a reminder,” he said. “I developed a hate for it, and I wish I could feel that way now about cigarettes.”

Courier wasn’t alone when it came to inside guys getting addicted, Kolibash reported.

“We had evidence that his right-hand guys got involved with cocaine, like Jesse Anderson and Jimmy Griffin. But those guys would never talk. They never offered anything,” he remembered. “The guys closest to Hankish never would talk, but a lot of the people on the fringes did. Like Donnie Clark. He was a drug dealer, sure, but he wasn’t a mobster.

“I went to the Pittsburgh prison with Tom Burgoyne to see Jimmy Griffin one more time just to see if he would give us anything on Hankish and the cocaine, but he remained 100 percent silent. We thought he might talk since he was likely going to die in prison,” he said. “He just shook his head no.”

Courier had quit trafficking before the federal indictments were published in the Wheeling newspaper on October 3rd, 1989, but he read the names of a lot of men he came to know well during his days as a drug dealer. Jacovetty, aka “Buddy,” and Joseph, aka “Chuckie,” and Tsoras, aka “Teddy” were a few listed, but he didn’t see Clark’s name and he didn’t see his either.

“My guy was Donnie Clark, and I knew he was talking to the feds but I didn’t exactly know what that meant. I remember in the beginning, Donnie used to say, “F-ck Hankish – he’s robbing people with his stomped-on sh!t,’ but I knew he was working with him for a while later on, too. So, I really didn’t know.

“The feds never came for me, and I still consider myself lucky as hell,” Courier added. “I know a bunch of years after all that, I officially met Tom Burgoyne. Nice man, but when he asked me what my name was, I was a little scared to tell him the truth. But I did. I told him my real name.

“He kind of paused when he heard it, too. Like it was familiar. But I just told him to have a nice day, and I walked away.”

The Series:

(Author’s Note: Each week I’ll be sharing a link to one of the chapters of my first “Wheeling Mob” series I wrote while serving as the founding editor-in-chief of Weelunk, a digital media site now owned and operated by Wheeling Heritage, a non-profit organization that promotes the history and heritage of the city of Wheeling.)

Thanks for sharing . I enjoy reading the articles .