(Publisher’s Note: The 12-part series, “The Children of Wheeling’s Mob Era,” will be re-published each evening over the next two weeks so those who missed some or all of the chapters will have another chance to read it. A collection of Steve Novotney’s mob stories over the years will be released in book form this summer.)

Prologue

It didn’t look like it does in those mafia movies like “Goodfellas” and the “Godfather” trilogy. Wheeling’s mobsters weren’t well dressed, they didn’t all wear fedoras, and they didn’t kiss rings. They did kill, though. They did hurt. They played dirty, were mean minded, and they were vile creatures, especially during the three decades when Paul “No Legs” Hankish was boss.

The organized crime in Wheeling wasn’t what most would consider “mafia,” though, because family connections weren’t part of business with the two underbosses. Instead, it was a mob of thieves, bootleggers, bookies, hijackers, drug runners, pimps and prostitutes, and cold blooded killers similar to what this region of Appalachia was known for dating back to the days when the National Pike guided strangers to the original Gateway to the West.

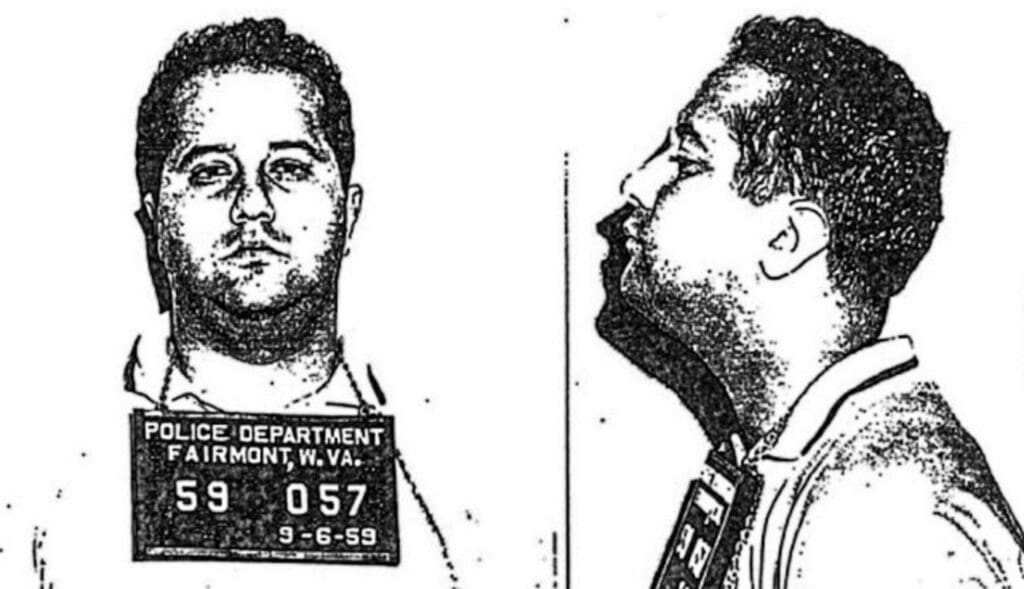

The recorded history of organized crime in the Wheeling area dates back to the 1930s when “Big Bill” Lias ran the rackets and the racetrack on Wheeling Island. Lias was a legit businessman with restaurants and bars, sure, but he also ran bootlegged booze, operated gambling rings, and was suspected but never convicted of shootings, home and business explosions, a few murders, and the car bombing of his archrival, Paul Hankish, in early 1964.

Lias was even questioned by investigators in the death of his first wife, Gladys, in 1934, but he also was loved by Wheeling residents because he gave away free turkeys during Thanksgiving holidays and brand-new televisions for Christmas. He was convicted of a few crimes and his Wheeling Downs horse track was seized by the federal government for tax evasion in 1952, but “Big Bill” prospered anyway until his passing in 1970.

Hankish was a different boss. He reined over a hierarchy far more extensive than what Lias operated because of purposeful expansions in prostitution, gambling, drug trafficking, and stolen goods, and he also became connected with underground rackets up and down the Ohio River and along the East Coast. Hankish was quick-tempered, dismissive of and demeaning to law enforcement, he loved to be feared, and he never cared much to endear himself to the general public.

But the general public sure did keep an eye on him and his men like sports fans watching the action of a big game.

Men and women and moms and dads saw what they saw, and so did their children because it all just looked like life in Wheeling, a city predominately hardworking, religious, sports minded, and middle class. Little leagues were popular, high school rivalries probably were taken too seriously, and pro players from the Pirates and Steelers were common customers of that “Wheeling Feeling.”

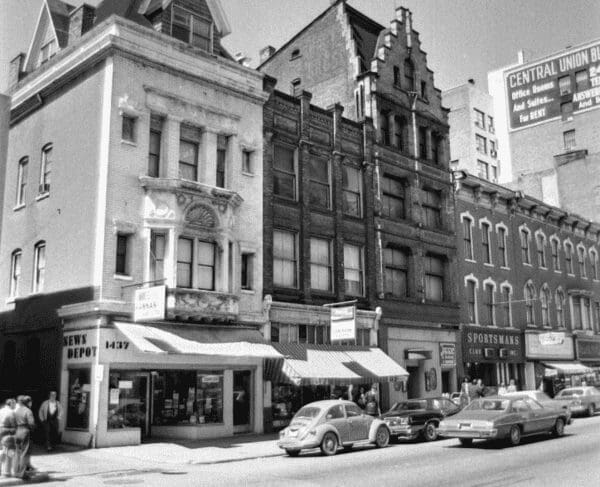

The Friendly City’s downtown from 50 years ago is recalled fondly because the streets were crowded with commerce and countless customers shopping at countrywide chain stores like GC Murphy, JC Penney, Sears, Value City, and National Record Mart. The Mendelsons, the Bourys, the Goods, the Posins, and the folks at Stone & Thomas added the local flare that older residents in the Wheeling area still yearn for today.

In many ways, the valley’s mob years proved to be a better time economically, socially, and, believe it or not, criminally. For the majority of the region’s residents, organized crime simply provided innocent amenities like those weekly wagers, slot machines, and back-room poker games. The population of Wheeling peaked in the 1940s and Main and Markets streets were lined with department stores and specialty shops, doctor’s and lawyer’s offices, and banks and bars and restaurants. The menus ranged from burgers and fried fish to prime rib and shrimp cocktail, and if you wanted in on “some action,” there were pool halls, back-room poker games, and “green door” brothels for that, too.

As it was, most men made a good living wherever he got dirty during the day, and mothers raised children and managed the households. It was considered the most wanted version of the American Dream at the time because the U.S. economy once allowed for stay-at-home moms to care for the kids, and Wheeling’s economy from the 1950s through the ‘80s included the ability to gain living-wage employment at mills, mines, and factories straight out of high school.

“Normal” was different back then.

It’s been rumored for six decades that Lias ordered the assassination attempt on Hankish on January 17, 1964. Hankish, then only 32 years old and married, may have lost his lower extremities in the bombing attack, but he gained the “Pauly No Legs” nickname, earned “invincible” status with the underworld, and became something of a folk hero throughout the valley and beyond.

If a resident ignored the mob, the mob ignored the resident. But if the resident wanted to place a bet, buy a date, purchase stolen goods, or score some cocaine, they didn’t have to look far.

The storytellers in this series are older adults today, but back in Wheeling’s heyday they saw what they saw and remember every detail from their younger years. They claim to know more than most after seeing secrets and hearing hushed details, and some were cops and lawyers and reporters from back then while others were the neighbors, the bartenders, the chefs, and the customers, too.

Some are still cautious and didn’t want their names named while others, like former United States Attorney William Kolibash, tells his tales with great detail after he and his agents picked apart Hankish’s intricate criminal organization that involved prostitution, stolen goods, tax fraud, drug trafficking, gambling, money laundering, and murder.

Sure, “Big Bill” got busted for tax evasion and was suspected of much more, but Hankish was credited by federal authorities for being an extremely intelligent man with an advanced criminal mind. In his prime, Hankish controlled the culture in night clubs, restaurants, billiard joints, and brothels, and he held the reins of his multi-million-dollar organization very tightly. Those who were loyal were rewarded, but those who failed him were discarded without regard.

Under Hankish, the mob was mean. It was nasty. It was cruel and it was deadly. People did the unthinkable, they did it for money, and they committed those crimes as many times as they had to so the cash continued to flow. Some of the felonious activities were kept out of sight like the truck hijacks, disciplinary beatings, drug drop-offs, prostitution, and murders, but most of the rackets were hidden only by the front doors of neighborhood bars.

The spot sheets, poker machines, game boards, and daily and weekly drawings were protected by a “wink-wink” mentality, and so were the bets with bookies and the sales of stolen goods at alleged discount stores like Ron’s Value Center near 22nd Street in Center Wheeling. The men who took orders directly from Hankish didn’t call themselves a “Mob,” and many of the family names most believe were involved with gangster activity actually were not.

Hankish played hard, though, and after copping a plea that ended a week-long trial in downtown Wheeling in October 1990, he paid dearly for his dastardly and deadly deeds when, at the age of 58, he was sentenced to 33.5 years in federal prison and fined $72,500.

When Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Jan Ackerman reported the trial results on October 26, 1990, the reporter stated in the article that the Wheeling area was known as an “Ohio Valley community (that) has long been a haven for gambling and open criminal activity.”

Ackerman also quoted Kolibash as saying, “(Hankish) was kind of a symbol of that attitude of permissiveness (in the Wheeling area), (with) people winking at criminal activity.”

Kolibash, now 80 years old, retired, and soon to publish his book entitled “Justice Never Rests: A U.S. Attorney’s Battle against Murderers, Drug Lords, Mob Kingpins & Cults,” recalls much more about the mobsters and the city’s culture of organized crime and he has shared those memories for this series of tales told by those who saw it, did it, felt it, and miss a time when live music, dance clubs, and fine dining was available in the area.

Kolibash remembers that version of the valley when he was a kid growing up in Benwood and attending Linsly Military Institute. He recalls what downtown Wheeling looked like when he started with the U.S. Attorney’s Office under Jim Companion in 1973. After a decade as an assistant federal prosecutor, Kolibash was nominated to be the U.S. Attorney in the Northern District of West Virginia by President Ronald Reagan in 1982 and was confirmed by the U.S. Senate.

He remained in the position until 1993 when he moved on to private practice, but it was Kolibash who was the quarterback for the “dream team” task force that dismantled organized crime and sent “Pauly No Legs” Hankish to prison for the final time.

And he has stories to tell, too, and that’s why Kolibash talks about FBI agents Tom Burgoyne and Dick Jones, and about Pat Butler when he was with Wheeling Police, mob muscleman Jesse Anderson and his bright yellow three-piece suits, and the pay phones Hankish used daily because he believed the feds had his phones bugged.

Kolibash tracked the mob’s trail of corruption up and down the river and to places like Pittsburgh, New Jersey, and Miami, and he picked apart a complex criminal organization that was, for years and years, invisible in broad daylight. Before the prosecutor and his team began sting operations, for example, there were more than 20 brothels in South Wheeling, a bookie and a coke dealer in every bar and pool hall, stereo Hi-Fis without serial numbers, bootlegged beer hidden away in alley garages, and a growing Missing Persons list.

This series of short historical stories will tell the truth and reveal the criminal-yet-accepted culture that once existed in all corners of the Upper Ohio Valley, and the writings will explain – thanks to eyewitness accounts – the pros and cons of living side-by-side with organized crime while also dissolving illusions about legends many believe these days when it comes to Wheeling’s two infamous mob bosses.

It was the “Wheeling Mob,” indeed, but it was this Wheeling Mob.

(Cover photo archived by James Thornton)