(Publisher’s Note: This is the second and final chapter on the history of the historic incline.)

Fox Hunts and a Bear Feast

Throughout the first year of the park animals played a major theme, intentionally, and unintentionally.

In the summer of 1893, a black cow had taken up residence at the park. The newspaper reported that “he is a sociable fellow and makes up with visitors right along.” During the fall of 1893 an “uncommonly large black cat” made a new home in the Mozart Park engine room. Because the cat was believed to bring good luck, he was reported as being fed very well.

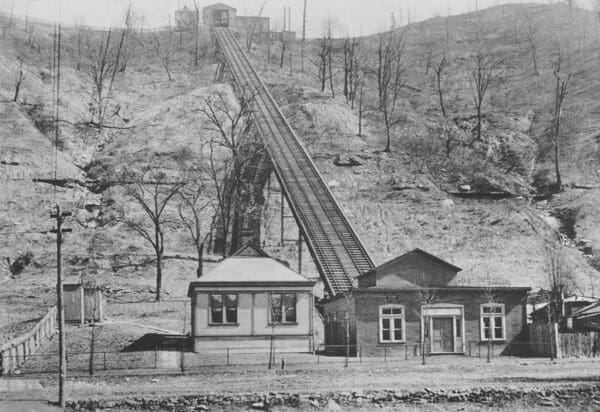

In January of 1894, 400 people and 25 dogs went up the incline for a foxhunt. It was reported the fox was given a 250-yard head start, the dogs were unleashed, and a Wheeling hound captured the fox and tore it limb from limb.

A zoo also was planned at the park, and one of the first animals on display was a black bear named Bruin. Bruin had lived in a cage at the park for about a year when it was decided that he was becoming a nuisance and an unnecessary expense, and unfortunately for Bruin, the park’s solution was a bear feast.

Bruin was slaughtered and frozen, and the park geared for a February feast that was scheduled to take place on George Washington’s birthday. Events included games, bowling in the afternoon, and the feast began at 5 p.m. in the restaurant. The event was predicted to be “one of the nicest events at the park.”

The festivities went as planned and were enjoyed by all, but those who had taken part in the bear feast said that Bruin meat was very tough.

The South Side Bowling Team

Bowling was one of the park’s greatest pleasures and a very popular sport during the era. South Wheeling even had its own bowling team that was sponsored by Henry Schmulbach, and it was called the South Side Bowling team.

On February 20, 1894, after beating the Intelligencer Team in Wheeling, Schmulbach took the team to Gavin’s Hotel on Main Street which specialized in choice wines, liquors, and meals at all hours. Schmulbach paid for all of the club’s expenses and the newspaper reported, “after the feast, a general good time was had till late in the night.”

On another occasion, 25 employees from the Schmulbach Brewing Company went bowling at the park. They split into two teams, drivers vs. the workmen. The drivers won, and all reported they had a pleasant time.

A World of Entertainment at Mozart

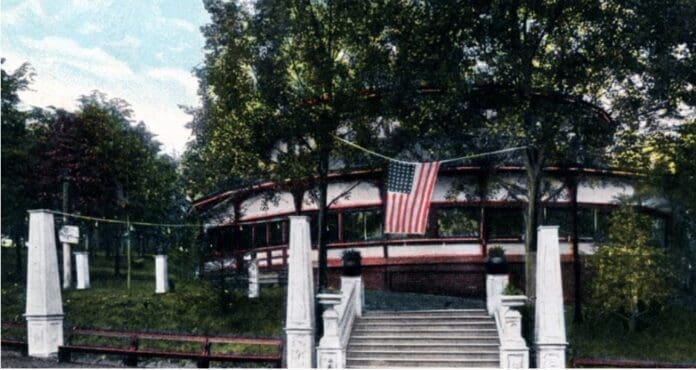

Throughout the year 1894, the grounds of the park continued to be developed, and buildings expanded and were finished until the park would be able to boast the following features: a dancing pavilion, a casino, restaurant, bowling alleys, an outdoor stage, and a one-third long bicycle track.

When the bicycle track was being excavated, workers discovered an ancient burial site that contained skeletons of two human beings. It was believed the site dated back to the times of the mound builders. The skeletal remains were passed into the hands of park employees and have since disappeared.

During the spring of 1894, the park’s closing time was 8 p.m., but after the installation of electric lights, the closing time was changed to 11 p.m. Sixty arc lights were installed along with hundreds of incandescent lights that were wired to the Schmulbach Brewing Company, which contained its own power plant.

Success and popularity continued with the second season of Mozart Park. One of the season’s first major events was a celebration for Decoration Day (which would be later known as Memorial Day). On this special day, the park announced it would award a silk parasol and umbrella to the best lady and gentlemen waltzer.

Another major event during the summer of 1894 occurred on July 1. On this day Mozart Park entertained students from Wheeling’s public schools. A total of about 4,000 students and parents attended the event, and each group was given a basket lunch. Students played games on the grass, bowled, and danced. One girl, though, 14 years of age, had a sunstroke while dancing on the pavilion, but she was revived by a physician.

Schmulbach’s Make-A-Wish Surprise

In November of 1894, Henry Schmulbach attended the park for the evening, and after watching his team bowl a few games (which they lost), Schmulbach decided to leave, but he was asked to stop at Mozart Hall. He was under the impression he was going to be attending a birthday party for a friend, but he soon realized it was a party to celebrate his 50th birthday.

Speeches were given, and about 60 guests joined in dancing and refreshments.

One of the largest and most controversial events to ever take place at Mozart Park occurred on July 23, 1895.

It was called the Centennial Celebration, which was meant to commemorate the formation of the town government of Wheeling. Because this was meant to be such a civic-minded celebration, there were some in Wheeling who frowned upon the idea that this event was to take place in a beer garden.

The main person who led this protest was Dr. Albert Riker of the 4th Street Methodist Church.

Mozart Park vs. Prohibition

Dr. Riker led lectures about what he called the evils of society, such as alcohol, gambling, theatres, and dancing – among many other topics.

One lecture claimed that Wheeling drinkers spent over $4,000 a day, which added up to over a million dollars a year. One of his most well-noted lectures across the East Coast was titled “What Shall We do with the Boys?” In Dr. Riker’s lecture against the celebration taking place at Mozart Park, he said, “Some say it is not a beer garden. It is a beer garden. It is nothing better. It exists for the sale of beer, and it has no other object.”

Riker would go on to say that Mozart himself must be turning over in his grave and that his bones rattle with holy horror, because such a place is named after him. Riker continued by saying even though cities such as Cincinnati, Chicago, and New York are wicked cities, even they would not hold their city’s centennial celebration in a beer garden.

Riker went on to say Wheeling was setting up an altar to Grambrinus and declaring him king (who was the king/God of beer). He closed his sermon by urging people to think of the children, the Sunday schools of this city, and not attend the celebration.

German Heritage Fights Back

On the day of the celebration, the weather was threatening but did not stop the approximately 1,500 people who made their way up to the park for opening celebrations. At about 2 p.m., special guests made their way south from the McLure House to the top of the hill where they gave animated speeches about the founding and history of Wheeling.

In an address given by Dr. Ulrich, he described his journey from Germany and his arrival in Wheeling in 1836 at age 10. He also referred to the great influence exerted by the German citizens of Wheeling and said because of their power it could be said Wheeling was half German. He went on to eulogize the city, its parks, and suburban railroads – specifically Wheeling Park and the Elm Grove Railroad, which had been started by Germans.

He ended his speech by saying that some reference had been made at a recent pulpit utterance against the holding of the celebration in a beer garden, and he said that “although a man might have to pass 25 saloons a day, he need not go in and drink, and in the like manner he might attend a pleasure ground where beer was sold, among other things, without sacrificing either character or convictions.

The beer element, he said, had done much for Wheeling, and could be depended upon to do more in the future, despite such uncalled for and unseemly attacks.

As evening approached, attendance at the park increased. At 6 p.m. streetcars in downtown Wheeling and Benwood were filled to capacity while a steady stream of pleasure seekers poured into the lower station building of the incline. By 7 p.m. the streetcars arriving at 43rd Street were not only crowded but men could be seen holding on to the cars with every protection.

By 9 p.m. there were between 8,000 and 9,000 people at the park. The evening ended with fireworks, and it was long after midnight until the last group descended the incline to go home.

These types of events described here would continue throughout the existence of Mozart Park. Groups such as the Mozart and Beethoven singing societies made Mozart Park their home. Other groups and organizations such as post-office employees, grocers, and locomotive engineers held events at the park.

Operas and vaudeville shows were popular and attended at the park, along with other types of amusements such as balloon ascension and parachute jumps. Sadly, the balloon failed to hold air and ripped.

Another major event was the musical production “Battles of Our Nation,” which had scenes from the wars of 1776, 1812, and 1861-65, and a cast of over 200 people. It was performed on the outdoor stage.

The park continued to prosper but took a major hit when prohibition was passed in West Virginia in 1913 and was implemented in 1914. Part of the park’s entertainment and the atmosphere was the beer garden, which was a major part of German heritage and culture was forced to close.

As Schmulbach was also forced to close the brewery on 33rd street, one can only imagine the stress and anxiety Schmulbach went through as he closed an industry he made very powerful in Wheeling. Two years later, in 1915, Henry Schmulbach died, but the park remained open until 1918.

After Schmulbach’s death, the park activity and entertainment gradually dwindled. With the outbreak of World War I and anti-German sentiment, the park was unable to withstand its financial capabilities. Afterward, the executors of Schmulbach’s estate began selling portions of the park, and that is how the community of Mozart started.