(Publisher’s Note: John W. Miller is a professional journalist who has crossed the globe searching the next best story, and one of his favorite places to discover such tales is Marshall County. His blog, Moundsville.org, has a plethora of articles about the destinations, including the one that follows.)

The obituaries for Phil Niekro, who died of cancer at age 81 on Dec. 26, focused on his legendary knuckleball. In the Ohio Valley, the Appalachian mining country southwest of Pittsburgh where “Knucksie” grew up, the Hall of Famer is also remembered as a loyal friend, enthusiastic booster, and son and grandson of hardworking Polish coalminers who lived a thrilling American dream.

This immigrant’s fable that ends with a celebrated millionaire athlete conquering America for the Braves and Yankees begins in 19th century Poland, where Phil’s grandfather, Jozef Niekra, was born in Slodkow, so-called “Russian Poland”. He emigrated to West Virginia around 1901, and strapped on shovel and axe to dig for coal underground. He married Magdalena “Maggie” Mieszegr, from Blinow, Polish Russia, only a few weeks after her arrival in America, according to Tom Hufford’s excellent essay for the Society for American Baseball Research.

Phil Niekro, Sr., name now Americanized, was born in 1913. Both his parents died before he turned five. After minimal schooling, he also went to work in the mines, when he was 15. He married another Polish immigrant orphaned young, Henrietta “Ivy” Klinkoski. They had three children — Phyllis, Phil, Jr., and Joe, and settled in Lansing, Ohio, seven miles west of Wheeling, WV.

That’s where Phil, Jr. and Joe starred for Bridgeport High School in the 1950s. When he wasn’t slogging away in the mines, Phil Sr. pitched in the Mine Workers League, the kind of amateur baseball that used to proliferate all over America. A coworker showed him how to throw a knuckleball, which he taught his sons. Phil, Jr. practiced with his childhood friend John Havlicek, the Boston Celtics Hall of Famer. “The only things I could ever do better than John was catch fish, shoot squirrels and throw the knuckleball,” Niekro said.

Always a Bulldog

Amazingly, Niekro threw his knuckleball for Bridgeport High. In the only game he lost, he gave up a home run to future Pirates Hall of Fame second baseman Bill Mazeroski, which is crazy because it feels like Maz belongs to the 1960s and Niekro to the 1980s. At 19, he rocked up to an open tryout for the Milwaukee Braves with 150 other kids on a place in the Ohio River called, simply, The Island. He got $500 to sign. The year was 1958.

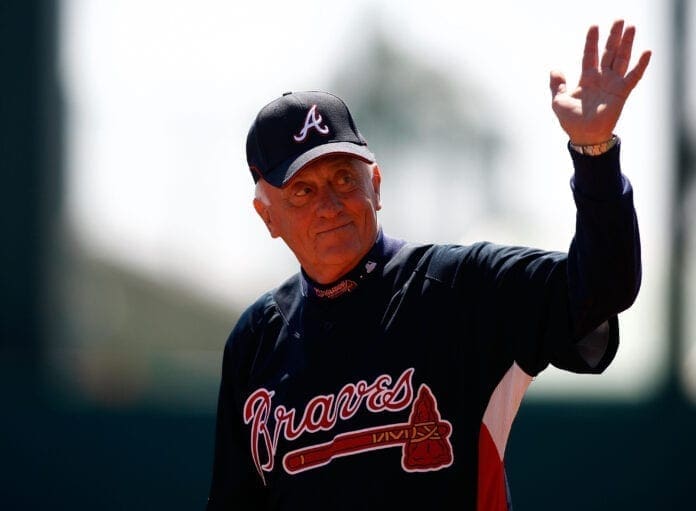

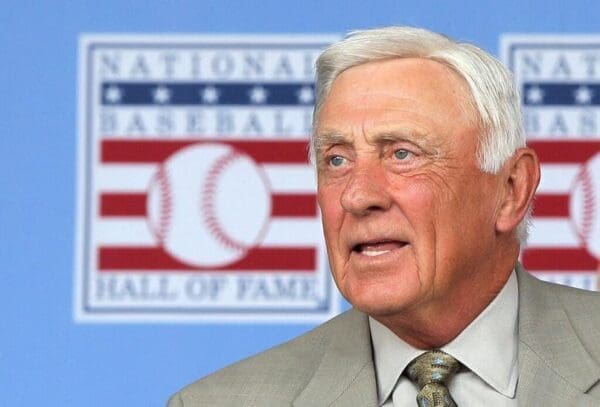

Phil made the majors in 1964. Over the following 23 years, mostly playing for the Atlanta Braves, he pitched 5,404 innings, won 318 games, and struck out 3,342 batters. In 1997, baseball writers chose him for the Hall of Fame. You can read all about it in the obituaries. He was also a very funny man, appearing on Dave Letterman twice.

The story I’d like to retell here happened on October 6, 1985, when Phil Niekro pitched one of the most remarkable games in baseball history, for the New York Yankees against the Toronto Blue Jays. It’s available for free on Youtube, and I recommend watching as a snapshot of 1980s hardball, portrait of Reagan’s America, inspirational sports movie, and primer on pitching strategy, guts, and guile.

For weeks, Niekro had been chasing his 300th win, after capturing his 299th on September 8. He was 46 years old, so it wasn’t clear he’d ever get there. In Wheeling, WV, 72-year-old Phil Sr. was in a hospital fighting for his life. The hospital put the game on the radio. In Toronto, Joe Niekro, who also pitched in the Major Leagues and had just been traded to the Yankees, kept tabs on Phil, Sr., with help from manager Billy Martin and owner George Steinbrenner.

The Big Leagues

In the stands, childhood friend Gordie Longshaw was thinking about a conversation at dinner the night before. “The Yankees had just gotten eliminated,” he said, “and, according to Phil, Billy Martin got so drunk he passed out on the trainers’ table, and [baseball great] Al Oliver [of the Toronto Blue Jays] came by the table, and Phil said, I’m not going to throw you a single knuckleball tomorrow.”

Longshaw, a 73-year-old retired educator and county commissioner who now owns City Advertisers in Bridgeport, OH, grew up with the Niekros. “My dad worked in the same coal mine,” he told me. “Phil was quick-witted, and Joe was more moody like their mother.”

I love watching this 1985 Niekro game against the Blue Jays. Sure, it was a meaningless game. Both teams were exhausted from the season and almost certainly hung over. The strike zone is a billboard wide. “They better be cutting and slashing from the time they leave the dugout,” says Phil Rizzuto on the telecast. But still. The Big Leagues.

And Niekro pitches a shutout, concluding with his only three knuckleballs of the day. “An astounding switch in strategy and style,” Murray Chass called it in the New York Times. He throws the craziest mix of junk I’ve ever seen — curves, slurves, eephus pitches, slow, slower and slowest. Just watch. It’s a thing of beauty.

In the 9th, Billy Martin sends Joe out to catch his warmup tosses. After the game, Joe comes out to congratulate him and tell him their dad is feeling better. “The nicest feeling of the whole day was right after I came off the mound Joe told me they took my dad out of intensive care,” Phil said. “I’ll go home tomorrow. I’m going to take him my hat and give him my baseball. He was as much a part of these 300 wins as I was.”

After a pit stop in a midtown bar with Martin — “Billy wouldn’t let me just get on the plane,” said Longshaw, “he said, this here is a 300-game winner, you have to celebrate with us” — the coalminers’s sons fly to Pittsburgh, and drive to Wheeling to present Phil, Sr. with the game ball from the shutout. He would live three more years. Longshaw flew with them. “It was all very special,” he said. “Phil was a special guy. He always had a fun story to tell about George Steinbrenner.”

Together, Phil and Joe, who died in 2006, would win 539 Major League games, a record for brothers. (Phil Niekro, Sr.’s tombstone in Saint Anthony’s Cemetery in Blaine, Ohio has a baseball on top inscribed with the number “539”). When he beat the record set by the Perry brothers in 1987, while pitching for Cleveland, Phil joked that “you can’t find good polka music on a Tuesday night in Cleveland. If it had been Saturday, I’d have raised some hell!” Both brothers are in the National Polish-American Sports Hall of Fame.

He Always Came Home

In the 1990s, Phil and Joe coached the Colorado Silver Bullets, an all-women’s baseball team. “Women should have every opportunity to play competitive professional ball,” said Phil. He died as the greatest knuckleball pitcher who ever lived, and one of seven Hall of Famers to pass away in 2020, along with Al Kaline, Tom Seaver, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Whitey Ford, and Joe Morgan.

In the week after his death, local stations celebrated Phil Niekro as “a man that never forgot where he came from,” Bridgeport High School Athletic Director Greg Harkness told WTOV-9. “Whether it was the golf scramble in his name that benefitted the school or helping with the fieldhouse, Phil was a great contributor to the youth of Bridgeport.”

Phil and his wife Nancy retired to the Atlanta area, where their three sons live. The family, like millions of others, has left the Ohio Valley, an aging slice of the Rust Belt that has lost thousands of factories and millions of people, a story chronicled in Moundsville.

But Phil grew up in a different world. He once took Braves teammates Bruce Benedict to visit. Niekro “showed me the fields where he used to play ball,” Benedict told Steve Wulf of Sports Illustrated in 1984. “His mother is the best cook in the world—we had stuffed pork chops and cabbage roll. We went over to the Polish Club, and those guys put down a shot with every beer. Before I knew it, I got floppy-legged.”

When “Phil drove through the Wheeling tunnel, he’d say ‘I’m home’,” Gordie Longshaw said. “He never forgot his roots.”