In the early 1800s, Virginia settlements extended westward across the mountains. As the Western population grew, the representation needed to catch up. A constitutional convention convened, in Richmond, on October 5, 1829. The region that would become West Virginia would have twenty-nine delegates, and the rest of Virginia would have ninety-eight. In the West, calls for secession from Virginia soon began.

Sectional strife continued into the 1850s. This resulted in a secession movement that gathered steam upon the election of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s election fueled the flames of secession. South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860, and was quickly followed by the deep south states. Virginia, however, remained with the Union.

Facing intense political pressure, Unionist Governor John Letcher called an extra session of the General Assembly to meet on January 7, 1861. A Secession Convention, convening on February 13, 1861, was authorized. Any decision made had to be ratified by a statewide referendum. Speeches by secessionists led by former President John Tyler and former Virginia Governor John Floyd were filled with fiery rhetoric. A vocal opponent of Tyler and Wise was John Carlile. Secessionists did all they could to prolong the convention. On April 4, they forced a vote on an ordinance of secession. A two-thirds majority defeated the ordinance.

On April 12, Confederates fired on Fort Sumter. Three days later, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. On April 17, many delegates had a change of heart, voting 88-55 in favor of secession. Representatives from the western counties left Richmond quickly. When delegates from the western counties returned, they found many citizens wanting to secede from Virginia. On April 22, a meeting called the Clarksburg Convention was called for Harrison County. This meeting resulted in calls for a larger convention in Wheeling on May 13, 1861, to discuss a suitable course of action.

Legislative Approval?

On May 13, 1861, 436 delegates from 27 Virginia counties assembled at Washington Hall in Wheeling to consider responsive action to the Ordinance of Secession. One group of representatives, led by John Carlile, advocated immediate action to form a new state. Waitman Willey wanted to explore the formation of a new state after the voting. Carlile and Willey became united in support of a new state. The convention adjourned pending the results of the May 23 referendum. With decisive margins in Eastern Virginia, the Ordinance of Secession was quickly ratified.

The Second Wheeling Convention returned to Washington Hall on June 11, 1861. The next day, proceedings were moved to the Custom House (currently Independence Hall). The chief question was whether to form a new state or reorganize the Virginia government. Dennis B. Dorsey (Monongalia) spoke strongly for the swift formation of a new state. John Carlile, once an outspoken proponent for the immediate formation of a new state, now advocated the reorganization of Virginia’s government.

A provision in the United States Constitution requires permission from the legislature of a state to form a new state within the confines of its borders. With Virginia’s secession, the legislature and officeholders of the state had abdicated their positions. With a reorganized government recognized by the federal government, permission for a new state could be secured. On June 19, delegates voted on the Reorganization Ordinance, passing it unanimously. Francis Pierpont was nominated and elected to fill the Restored Government’s governor post.

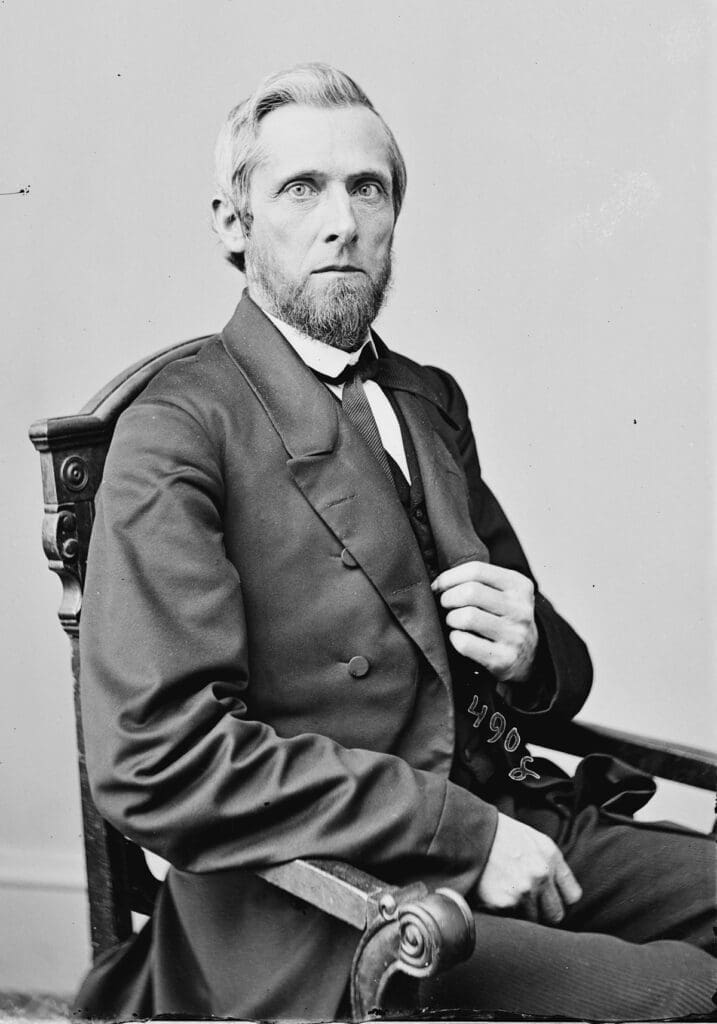

The convention was adjourned, scheduled to resume on August 6. Governor Pierpont then called a special session of the General Assembly. He informed delegates that President Lincoln indicated that he would call a special session of Congress. Since the two Senators from Virginia had “vacated” their offices, Lincoln recommended the election of Senators to fill the two seats. John S. Carlile and Waitman T. Willey were elected to fill the seats. On July 13, Carlile and Willey presented their credentials to the Senate. Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee asked that Carlile and Willey immediately be sworn in. After some initial objections, the two were approved and sworn in thereafter.

Drawing Borders for #35

The Second Wheeling Convention reconvened at the Custom House on August 6. The identification of counties that would comprise the state, as well as its boundaries, was discussed. The Re-organization Ordinance was approved by the voters overwhelmingly, with 18,408 in favor of a new state and 781 opposed. Delegates were also elected to the Constitutional Convention slated to begin November 26, 1861.

Delegates returned to the Custom House in Wheeling on November 26 to determine the new State’s Constitution. There was a sentiment that the name Kanawha be given to the new state. After some contentious debate, delegates wrote their preferred name on paper. If one name received a majority of the votes, then that name would be the one chosen. With a two-thirds majority, West Virginia was a clear choice, and the convention adjourned, resuming on January 7. For six weeks, delegates discussed affairs of government. On February 14, the Constitution was put to a vote. Its adoption was unanimous. On April 3, the voters overwhelmingly approved by a vote of 18,862 to 514.

Before West Virginia could petition for statehood, there was one more hurdle to clear: the United States Constitution. To meet the terms of Article IV, Section 3, creating a new state, permission was required from the Reorganized Government of Virginia, now recognized in Congress as the legitimate government of Virginia. This government had the authority to grant that permission. Governor Pierpont called the General Assembly of Reorganized Virginia into session at Wheeling on May 6, 1862. He presented the recently ratified Constitution of West Virginia and urged its passage. Less than one week later, on May 12, the act permitting the formation of West Virginia was passed.

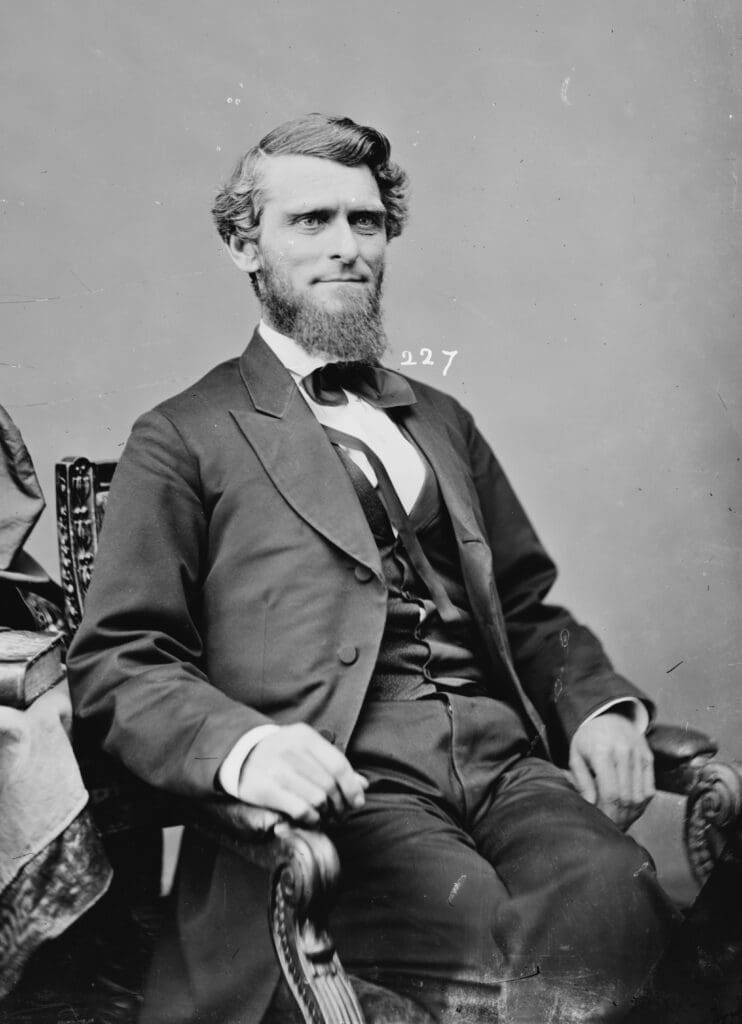

On May 29, 1862, Senator Willey introduced Senate Bill 365 to admit West Virginia into the Union. Carlile, a Committee on Territories member assigned to write the bill, unilaterally added many of his views. Willey was flabbergasted by these changes. The debate continued for six days, and the discussion grew heated, often involving Willey and Carlile. Willey, hoping to reach a compromise, proposed an amendment to the bill. A period of gradual emancipation would free all enslaved people in West Virginia. This would become known as the Willey Amendment.

A Traitor in the Midst?

On July 14, by a vote of 23-17, Senate Bill 365 was passed by the Senate, with Carlile one of the seventeen nays. The man who once championed statehood attempted to kill the statehood bill. Now viewed as a traitor, Carlile’s political career was over. Willey, like many West Virginians, did not understand the motives of his fellow Senator.

Ohio Congressman John Bingham helped guide the bill through the House. On December 9, the bill was debated for two days. Like the Senate, the discussion was often heated. On the afternoon of December 10, the House Speaker, Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania, closed the debate, and votes were cast. The final tally was ninety-six in favor of West Virginia Statehood and fifty-five opposed. One step away from Statehood, the bill was going to President Lincoln.

The President received the statehood bill on December 22, 1862. Now, Lincoln faced a dilemma. While supporting and recognizing the Restored Government as the legitimate government of Virginia, Lincoln was concerned about the bill’s constitutionality. Essentially, the Restored Government permitted itself to form a new state. On advice from Attorney General Edward Bates, Lincoln polled his cabinet and asked for a written statement from each. The cabinet was split 3-3 on the bill. Lincoln also wrote his answers to the questions he had posed. He used these answers to help him as he contemplated his response to the Statehood Bill.

On New Year’s Eve, Senator Willey and Congressman Jacob Blair called on Lincoln and spoke with him for three hours, discussing West Virginia statehood. Blair visited Lincoln the following day. The President greeted Blair, strode to his desk, removed a document, and showed it to Blair. It was the bill, and at the bottom of the document, Blair saw Lincoln’s signature along with the word Approved, dated December 31, 1862. West Virginia would become the thirty-fifth state in the Union. Blair immediately sent the news to Wheeling.

Before Lincoln could issue the statehood proclamation, the people of West Virginia had to approve a new constitution allowing for the gradual emancipation of enslaved people. The revised constitution was adopted in a reconvened session of the Constitutional Convention on February 17, 1863. Carlile worked to convince the people to reject the Constitution. Voters went to the polls on March 26. The Constitution, incorporating the Willey Amendment, was overwhelmingly ratified by a vote of 27,749 to 572. On April 20, President Lincoln issued the statehood proclamation to take effect sixty days later. Voters again went to the polls on May 28 for the election of State Officers. Arthur Boreman was elected as West Virginia’s first governor. On June 20, 1863, crowds gathered in front of Linsly Institute, the site of the Capitol building, to hear Governor Boreman’s inaugural address and celebrate the birth of the Mountain State.