(Publisher’s Note: This article was public on the blog Moundsville.org and has been shared with LEDE News by the author.)

Every December, until around 40 years ago, town leaders in Moundsville, WV erected a giant Christmas tree on top of the Grave Creek Mound. You could see it for miles around, all the way across the Ohio River.

Around 1980, Moundsville pulled the tree, as a sign of respect to Native American groups and their ancestors.

In town, however, people still talk about that tree. The inmates from the prison across the street “actually did the decorating,” said Tom Stiles, coordinator at the old Moundsville penitentiary. “They’d string up the old C-9 bulbs” and light up the mound.

“Growing up, I remember the Christmas tree,” Moundsville town historian Gary Rider told me. “It was just something you expected every Christmas.” People in town would have preferred to keep the tree up, and Rider himself didn’t see a problem with the tree “because it wasn’t physically damaging or altering the mound”, but they didn’t fight the request from Native American groups to take it down.

We included the story of the tree in our PBS film Moundsville because it told an interesting story about Americans’ relationship to their land, one of the main reasons for making a film in a town named after a prehistoric mound. You can’t live in Moundsville without confronting the fact that the U.S. is a country that’s existed for less than 300 years in a place where people have lived for over 10,000.

In our research, we couldn’t find a picture of the tree and the luminaries on the path leading to the top of the mound, but this past Saturday, I visited an open house at The Marshall CoUnty Historical Society, and found some uncredited pictures of the tree, which I’m publishing here.

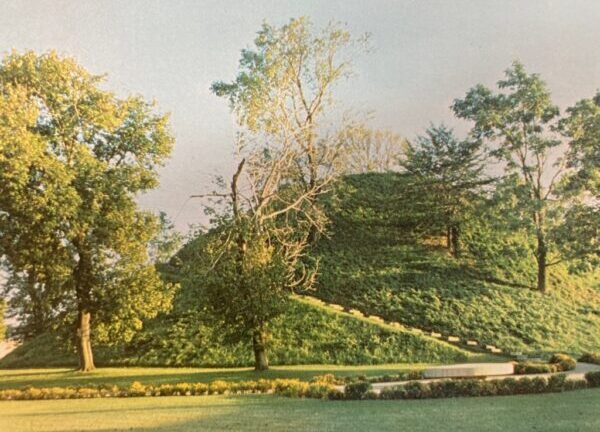

The 69-foot-high conical structure was built around 2,200 years ago to entomb three bodies from the Adena people, probably royalty. Taking down the tree was a way of respecting their lives, and those of Native Americans who lived in and around these lands for thousands of years.

They left behind thousands of mounds, most of which were knocked down by European immigrants as they rolled west in the 18th and 19th centuries. Grave Creek is a survivor, like a few thousand other sites, including Poverty Point in Louisiana, and Cahokia, near St. Louis, which is on the verge of being declared a National Park.

Mounds were built across a vast region, from Florida to Wisconsin, in all kinds of styles, often shaped like cones, but also sometimes like lizards, bears, birds and alligators. Serpent Mound, in Peebles, OH, is shaped like a 1,330-foot-long snake.

The mound in Moundsville looms over the town, and so did that tree.

“You could see the Christmas tree all the way to Ohio,” said Andrea Keller, cultural coordinator of the Grave Creek Mound.

The Grave Creek Mound has been a feature in the life of anybody who grew up in Moundsville. It’s where they went to eat ice cream and stargaze as teenagers. At one point there was a bar on top.

And it was an easy way to learn and think about history. “The mound was the first time I learned” about colonialism and “another group being invaded,” said Alexis Martinez, who grew up in Moundsville.

The Christmas tree “was a thing the city looked forward to each year,” said Stiles. “But that artifact of history was taken away from Moundsville.” For Stiles, who’s spent a life in Moundsville, the tree was an “artifact of history” that was “taken away.”

In our ongoing conversation about America’s complicated past, acknowledging Stiles’ point of view might be crucial. In fact, maybe it’s only Stiles’ love and nostalgia for the town’s Christmas tree that permits real dialogue.

If people in Moundsville hadn’t loved their Christmas tree, giving it up would not have been a significant act of respect and solidarity.

After 1980, Moundsville didn’t find another elevated place to put a Christmas tree. Said Rider: “That was our highest point.”