West Virginia’s $4.6 billion tourism industry is a treat for East Coast vacationers, from Blackwater Falls and New River Gorge to the mighty Greenbrier and, of course, Moundsville, whose touristic glories (such as the mound and the penitentiary) we elaborate on in our PBS film.

A state of treasures. Hours away from 50 million people. (The state registered 65.5 million visits in 2019.)

How to market West Virginia for tourists, a key part of any economic development plan as the coal industry declines, has been a trickier task than recognizing the state’s obvious beauty. In this century, tourism officials looking for catchy slogans have seized on everything from “Almost Heaven” to “Wild, Wonderful West Virginia.“

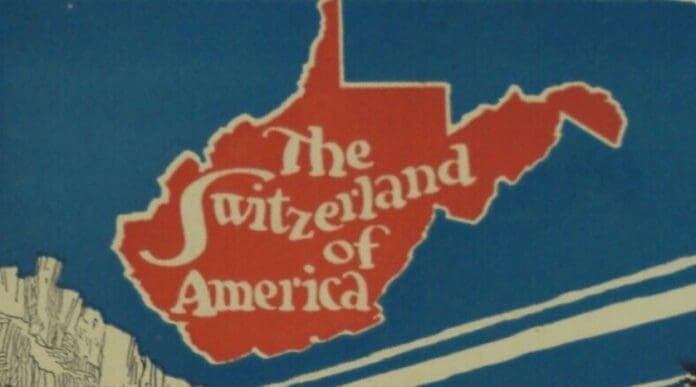

A century ago, the preferred designation was this: “The Switzerland of America.” And that, despite its intimation of bland neutrality, caused a war of words, illustrating the complexity of marketing a place as unique and misunderstood as West Virginia.

The term popped up in government and newspaper articles in the 1870s. It was more common then to describe American geography using Europeans references. From New Hampshire to Colorado, a lot of hilly places became the Switzerland of America.

But it took firmer root in West Virginia than elsewhere. A state-by-state list from 1896 even includes it as West Virginia’s official nickname.

In 1926, the state’s department of agriculture published a 48-page pamphlet, written by Russ B. Johnston, published by the West Virginia Department of Agriculture, titled: “The Switzerland of America.” Subtitle: “Tour West Virginia this year.”

The pamphlet declared:

West Virginia has much to offer the world. It has beauty unlimited and numberless points of interest to delight the tourist. It has good roads by which the tourist can visit these places. It has wealth and opportunity for those who would become permanent citizens.

Immediately, there was a movement to push back. As the Charleston Mail wrote:

We must recognize the fact that West Virginia is not Switzerland nor an imitation of it or a second addition of it. The fact is that West Virginia is West Virginia and this is sufficient. West Virginia is original and not a copy of something else. Let us acclaim West Virginia for what it is [and] not try to make it out to be something which it is not…

We must accept our mountains for what they are, entirely different from the Swiss mountains which are rugged and snow-clad and forbidding, different from the famous Rockies, some of which are like the Swiss. The distinctive features of the Swiss mountains are grandeur, and sublimity; of West Virginia’s, beauty.

One reason the state launched an official promotional campaign has nothing to do with tourism. The 1920s were a boom time for driving in West Virginia. Cheap Model-T Fords flooded the market. And the state finally modernized its roads. “What existed for roads was a mess, and they wanted to push the idea of state roads,” Stan Bumgardner, editor of Goldenseal, a West Virginia quarterly devoted to the state’s culture and history, told me. “Every county managed its own road. If you were driving from Marshall Co. to Ohio Co., you had a decent road and suddenly you’d hit the Marshall Co. line and you wouldn’t even have paved road.” When the decade started, no two major towns in the state were connected by proper roads. When they started upgrading roads in the 1920s, state officials needed to convince residents and taxpayers that it would be worth it.

The 1926 pamphlet said:

Since West Virginia opened up its system of well-built roads that make it easy to cross the highest mountains by gentle grades and to explore many regions largely unknown in the past, West Virginia for the first time can show the world that it is “The Switzerland of America.”

A score of lofty mountain peaks break the 4000-foot level. From these heights, torrential streams foam and dash their way to the lowlands in beautiful waterfalls and roaring rapids through yawning chasms and deep, dark gorges. These streams are the source of two million potential horse power in hydro-electric energy, which, added to the wealth of coal hidden beneath the surface of the state and its natural gas, makes the West Virginia the greatest power house.

Of Moundsville, the document noted that the town “owes its name to Grave Creek Mound, the largest ancient mounds of its kind in America.” It falsely claims that the mound “is doubtless centuries older than the tomb of King Tut” and that “its vicinity is considered to have been the capital or headquarters of this race.” The actual construction date of the mound is estimated around 250 BC, over a millennium after King Tutankhamun, who lived in the 14th century BC. And it was a prehistoric burial mound that belonged to the Adena people, not part of a large urban congregation. Another fib: The report says that the skeletons found in the tomb were “almost eight feet tall.” True: “many ornaments of mica, bone and metal were found.”

West Virginia has been attuned to the promise of tourist dollars for a long time. In the first half of last century, the Greenbrier resort, which has hosted 26 presidents, was one of the ritziest luxury spots in the country. In 1945, the Raleigh Register of Beckley, WV noted that

now is a good time to be thinking of the tourist crop in West Virginia’s economic setup. In the last year before the war put a crimp in the free movement of people about the country, the state’s income tax from that source exceeded the total farm income by 30 per cent. Nobody had noticed it. Everybody was surprised by the figures– $52,000,000 from tourists, $40,000,000 from the farms. The tourist business had just crept in rather unawares….

West Virginia could become a kind of tourist paradise, like the real Switzerland. It wouldn’t take a vast amount of money or effort. Nature has already done the big end of the job. We only need to add airports, more roads, and attractive accommodations. Then just a few touches here and there to heighten the beauty, like a pretty girl with a bit of make-up.

In addition, since the 19th century, West Virginia has had a tiny town called Helvetia, settled by Swiss immigrants. It’s a quaint, charming tourist hamlet, that carries on “Swiss traditions, but Swiss Appalachian traditions”, including a Swiss version of Mardi Gras called Fastnacht, said Bumgardner.

In the end, as wished for by the anti-Swiss movement, the name didn’t stick. The last “Switzerland of America” mention I found in newspaper archives is from 1977. West Virginia, the article said, “used to have billboards along its roads proclaiming: ‘Welcome to West Virginia, the Switzerland of North America.’” The story includes a quote from a historian who noted that “the people of West Virginia and eastern Kentucky have gotten exceedingly poor in a rich land, while the people of Switzerland have gotten rich in a poor land.”

That fight for more prosperity is still going on. Is tourism the answer?

“Tourism can make us more prosperous but it’s also difficult because it’s another cyclical industry,” said Bumgardner, mentioning businesses he knows that have closed. “And we need the investment in breweries and restaurants that can serve people when they do choose to come here.”

One thing is certain. As the 1926 editorial fulminating against the Swiss comparison pointed out: West Virginia “does not need overstatement.”