(Publisher’s Note: This article was originally published more than a year ago but we’ve made it available again because, with the beginning of spring upon us in the Upper Ohio Valley, some adventurers may decide to venture inside this historic cavern. If that’s the case, PLEASE be careful.)

Photography by Raina Burke

He owned no cabin and no farm, and he didn’t have a job either. He just killed and that made other settlers feel safe, so Lewis Wetzel continued to avenge his father’s, brother’s, and sister’s deaths in 1786 by collecting the scalps once owned by enemies.

His father, John Wetzel, colonized Wheeling the same time the Zane clan did, and in 1782, a 19-year-old Lewis joined the same fight for Fort Henry when Betty Zane made her historic run for gunpowder. He was the fourth of seven children, and he was a hero to the white man and a murderer to the natives.

It was the days of the Revolutionary War Era, a time celebrated for the growth of American colonization because the horrors of invasion were costumed as necessary.

“There are many stories about the battles that were fought in this area and we tell many of those stories still,” said David Perri, one of the organizers of the annual Fort Henry Days. “The stories about Lewis Wetzel, though, are usually shorter because he usually was the only one around when he attacked because that’s how he worked.

“He helped defend Fort Henry in 1782 because that battle was a community effort and he was nearby at the time,” he explained. “But that was rare, according to the records we have to work with now. Most of the time, by all accounts, Lewis Wetzel was just out there looking for more because there were not enough braves he could kill to get revenge for his father and his brother.”

One place where Wetzel resided was a cavern that since has taken his name. He was told of a suspicious turkey call heard consistently along the waterway now known as Big Wheeling Creek, so he tracked it to an overgrown area about 60 feet above the tributary. According to the legend, Wetzel then shot to death a native who emerged from behind the bushes and vines to squall the call one final time.

Wetzel quickly discovered the brave had been living in a cave.

A Creation of Time

There are no historical markers and no such protections either. There is, though, a path worn by the curious.

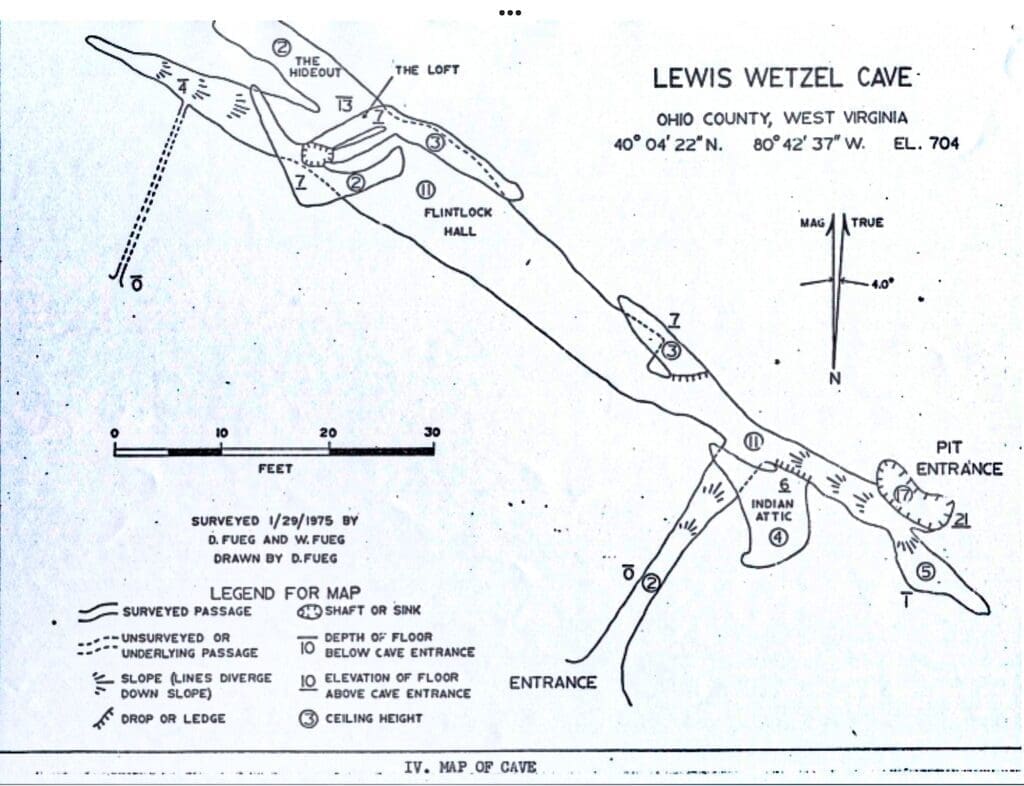

The entrance is narrow. The interior is pitch black. Once inside, voices echo without offering a sense of direction. There are critter bones scattered about, and level ground is rare. Some areas are five feet high, others two, and one area extends 165 feet in length.

Over the years, some areas of the cave have been named by amateur adventurers including “Flintlock Hall,” a carved clearance measuring 10 feet wide, 11 feet high, and 60 feet long. There’s also “The Hideaway,” “The Attic,” and “The Getaway.”

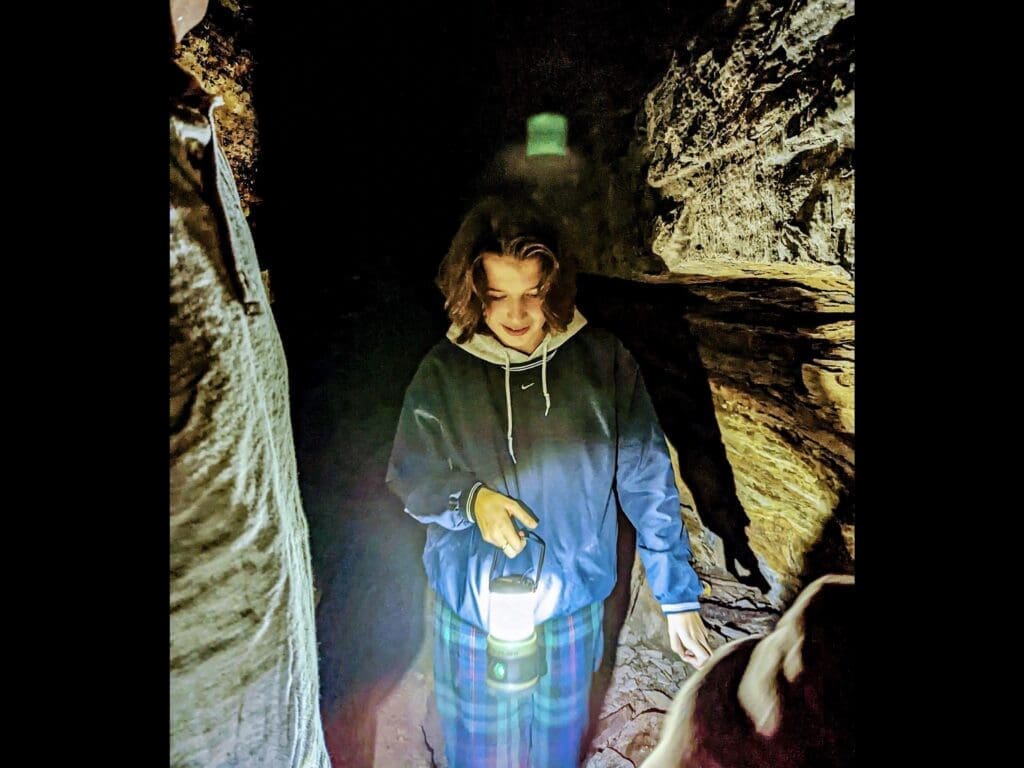

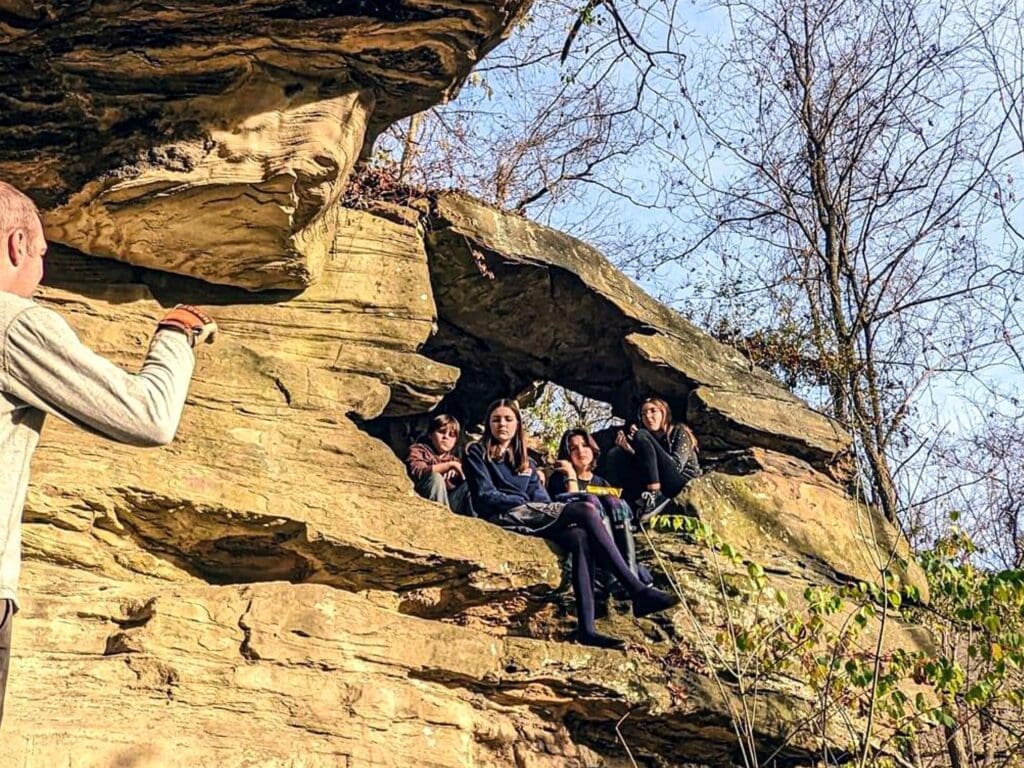

Raina Burke, a local physician and parent of daughters who attend Wheeling Country Day School, is assisting this academic year with the teaching of West Virginia history to eighth graders. She and her husband, Steve, recently ventured to the Lewis Wetzel Cave with four students, including their daughters Jules and Sydney, and Ella Landini, Mac Parsons, and Micah Dodd.

“That was the second time I’ve been in there and my husband has researched it pretty extensively,” Burke said. “The first impression I have had each time is that it is bigger than you imagine before going in, and that it just goes on and on, too. The hallway is really, really long and there are turns you can take, too, as long you remember to watch the ceilings because they get pretty low in some areas.

“This most recent time we didn’t stay in the cave for a real long time because one the kids got a little anxious because of claustrophobia, but it’s still a fascinating thing to see,” she continued. “There are signs people have been in there, of course, but just to see what nature created is pretty fascinating to me.”

The students also will visit Independence Hall in downtown Wheeling, the former W.Va. Penitentiary in Moundsville, and the town of West Liberty since it is the eldest of all Northern Panhandle communities. At Country Day, the class is known as West Virginia Club, and it is a more engaging version of the historical lessons learned by most Mountain State children.

“Anyone who grew up in the state of West Virginia remembers having West Virginia History in the eighth grade, but at Country Day we’re doing it differently than when I was in eighth grade at Bridge Street. We didn’t take any field trips back then,’” Burke explained. “So, while we’re learning about the state, we go to places where some of the history has taken place, and the Lewis Wetzel Cave is one of those places.

“We’ve just started visiting these locations and along with the caves we’ve gone to the Mound in Moundsville, and we’ll go to Independence Hall and a few other historical places in the area,” she said. “It’s more enjoyable to learn by visiting the actual places than just reading about them in a book, so we’ll go to as many as we can before it’s time to take the Golden Horseshoe test.”

Hero or Villain?

His eyes were said to be jet black and his dark hair was down to his knees, and Lewis Wetzel was best known for being able to reload his rifle while running in the woods. The difference with him, however, was that he wasn’t running away but instead toward his next fight.

His primary enemy in the Wheeling region was the Wyandot tribe, and he utilized the perch from the cave to scout natives traveling along the creek while hunting the next meal. The entire cave rests in sandstone of the Conemaugh Series of the Pennsylvanian System, according to information archived by the Ohio County Public Library.

The Lewis Wetzel Cave, the website states, was formed by the faulting of this rock as a result of Wheeling Creek downcutting into its own valley. And Wetzel used it to assassinate at least 10 natives.

“You can read about Lewis Wetzel and why this is known as his cave, but once you see what he saw from where the opening of the cave is, you quickly come to understand why he spent so much time looking for the Natives who were hunting him, too,” Burke said. “It was a place of safety for Lewis Wetzel, and the area is very interesting because of the cave but also because of the overlook area that has a naturally made sunlight.”

Lewis Wetzel died from “yellow fever” in 1808 at the age of 45 at a cousin’s homestead in Mississippi, and his remains were moved to the McCreary Cemetery in Marshall County in 1942. Wetzel’s grave now is adjacent to his brother Martin and near the land that has become the Hare Krishna community known as “New Vrindaban.”

His nickname in the Wheeling area was “The Death Wind,” and that’s because legend has it, the frontiersman collected more than 30 scalps before leaving for the Louisiana Territory in the late 1700s to earn a living as a hunter and trapper.

“I’ve heard during my lifetime that he was something of a maniac,” Burke said. “But I’ve also heard the white settlers loved him and they were thankful because they were protected and he made them feel safe at a time no one knew what was going to happen next.

“It was a very different time back then and that’s why we brought the students here to learn it with a very hands-on experience,” she added. “They know what Lewis Wetzel did back then would have made him a serial killer today, but they also know now it’s what he had to do to survive because life was a really different experience. For a while, he had to live in a cave and now they’ve seen it for themselves.”