While growing up in the Triadelphia area I was always fascinated by many of the historical sites and buildings that I observed on my daily travels.

Entering the town and seeing the welcome signs which announce Triadelphia as the oldest town in West Virginia always made my mind wonder what this area would have been like to live in over 200 years ago. Triadelphia was incorporated on July 29, 1829, as the Village of Triadelphia by the Commonwealth of Virginia. Wheeling would not be incorporated until 1836.

Just the meaning of the town’s name alone is quite interesting too. The origin of Triadelphia’s name is derived from three settlers, Jonathan Link, Presley Peak, and William Hawkins who were killed by a band of 20 Indians along Middle Wheeling Creek in 1781.

As I explain to my History of Wheeling students at Wheeling Park High School, “The tri-part of the name is easy to figure out, but what does adelphia mean?” Wheeling has a strong Greek heritage and every year a few students always speak up and say “adelphia means brother!” And there you go, Triadelphia is named after three friends or “brothers” who perished there during the frontier era.

While traveling east through Triadelphia on the National Road you can find historic brick homes dating back to the early days of the National Road, remnants of the old Valley Camp Coal mine, and shortly after you encounter the unincorporated area of Roney’s Point.

The Legends

Roney’s Point is sort of a junction that connects you to Dallas Pike Road and, of course, what most people know today as a backway to The Highlands or Interstate 70. Roney’s Point, though, is so much more. I’m sure many of you notice the Old Stone House at the corner that dates back to 1818 as a tavern. It’s since been demolished, but there were also two other structures nearby that housed travelers.

There was also the old Southern States Co-Op that served farmers and residents throughout the area, and when the railroad was still running deliveries could be picked up at Roney’s Point.

At the junction of Roney’s Point, if you turn onto Point Run Road after a short ride you will encounter Country Farm Road which leads you to the ruins of an estate that was once owned by Henry Schmulbach. After his death the property was sold to the county and used as a poor farm, tuberculosis hospital, and later a mental hospital was built on site.

I plan on telling more of the Schmulbach story another time, but for this article I would like to focus on the Roney’s Point Cemetery that is located on four acres of the property. Residents of the Ohio County poor farm, tuberculosis hospital, and paupers were buried in this cemetery starting sometime after 1916. Approximately 59 graves that were moved from the Peninsula Cemetery in Wheeling were also reinterred at Roney’s Point to make room for Interstate 70 just east of the tunnels in 1964.

I had visited the cemetery for the first time on May 8, 2008, and after doing some more research recently of the property I was motivated to see what has changed in the cemetery since then.

Resting Souls

In 2008, the gates still remained the entrance to the cemetery.

So, on a warm May Spring day, I parked along Point Run Road with Brittany Fehr as my extra pair of eyes to locate the cemetery and explore. At the base of the cemetery, we walked through a small field. Someone had recently mowed a wide path through it which made walking through this part easy. In this field, I remember seeing a few grave markers, but on this day we could not locate them.

As you enter the woods and walk the path which was probably once a small road used to maintain the cemetery we found small cement markers with numbers on them. The markers appear as if they were tossed about on the ground, but after further examination, most have been disturbed from the growth of trees, brush, and years of neglect.

Our hike into the woods was more difficult than my first visit in 2008. Fallen trees and the overgrowth of briers made the trek a challenge. I was convinced that I led us too far into the woods and missed the grave markers I saw in 2008. We persistently kept pushing forward, though, and were able to discover an area that Brittany could tell that at one time was probably a clearing of property. After pushing through more brush we were able to discover small metal markers designating the location of those reinterred at Roney’s Point from the Peninsula Cemetery.

A walk through this brush lead to Peninsula Cemetery grave markers

The metal markers read “Unknown – Peninsula Cemetery – Grave # 713,” for example. These markers represent some of the 59 graves that were removed from the Peninsula and relocated to Roney’s Point. What has always struck me as odd is why the markers say “unknown.” Glenna Dillion’s Book, The Cemeteries of Ohio County provides a description and history of the cemetery, along with a list of those buried at the cemetery.

Grave #713 is not unknown at all. It represents John Bartkovich who was interred on October 19, 1966. The records also state that he was not an inmate and White.

Bartkovich was born on June 24, 1892 in Poland, served in the Polish army, and his death certificate indicates that he spent most of his life as a coal miner. He resided at 2148 Main Street at his time of death. It was unknown if he was married or widowed when he passed away. What remains a mystery is why the marker says Peninsula Cemetery when his death certificate says he was interred at the Roney’s Point Cemetery. It’s likely he was interred at Roney’s Point as a pauper, although that fact is not specified anywhere.

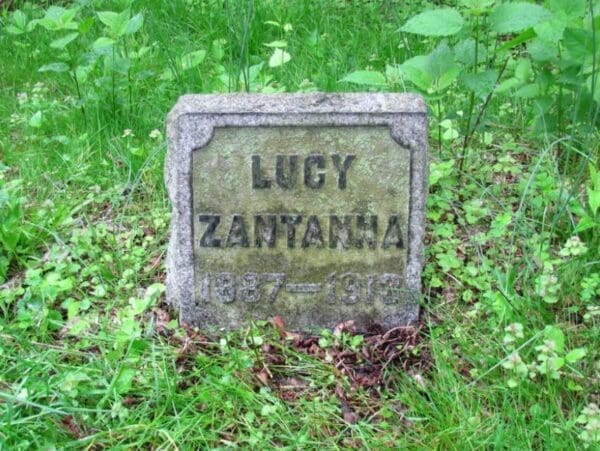

Another interesting point to make about those buried at the Roney’s Point Cemetery is the story of Lucy Zantanna. Zantanna has a monument at the cemetery that is dated 1913, the year that Schmulbach moved into his Roney’s Point mansion. Zantanna died April 22, 1913 in the rear of a home at 1204 McColloch Street. She was married, a housewife, and died from food poisoning. Zantanna ate raw oysters that had been kept in the family refrigerator Saturday afternoon until late Sunday without ice. According to her obituary, “When they were removed it is said they had a disagreeable odor but Mrs. Zantanna ate them, although others refused to do so.”

Within a few hours she became ill; a doctor was called who made every effort to save her, but she died shortly after. Zantanna was just 25 years old.

Zantanna was interred at the Peninsula Cemetery. Zantanna’s monument must have been moved around 1964 to Roney’s Point. What remains a mystery is where all monuments moved, and what is the story with those metal markers?

Upon further research, Zantanna had a 6-month-old child that died March 22, 1911 and was interred in the Peninsula Cemetery. Zantanna’s husband John remarried in 1915 and moved to his wife’s hometown in Pennsylvania. What’s unknown is where Zantanna’s daughter is now buried. Still in the Peninsula Cemetery? Possibly moved to another local cemetery? Records indicate she was not reinterred at Roney’s Point. This is another mystery for Brittany and me to solve.

The Road Goes Through

In September of 1963, it was announced in 60 days 1,100 graves would be disinterred by 14 experts in the field of moving graves to make room for Interstate 70 just east of Wheeling Tunnel. According to state law, it was also required that a certified mortician be on hand to oversee the project.

Cemeteries used for reinterment included Greenwood, Mt. Olivet, Mt. Zion, and the county graveyard at Roney’s Point. The article stated that a marker would be placed on each grave at its new location, known or unknown. It was also stated that all monuments would be reset on new foundations. That movement probably occurred in late 1963 and was finished in 1964.

Glenna Dillon’s research revealed that the last internment according to Ohio County records at Roney’s Point was in 1987, but her research all discovered internments as late as 1993.

Although the current state of the cemetery is in poor condition, it would be much worse if it weren’t for the efforts of Gary Kestner. In 1998, Kester spearheaded a movement to clean up the cemetery grounds and make an effort to keep the gravesites clear of future brush and tree growth. Kester sought help from the local community with clean-up, restoration of the wrought iron gate, and a new sign was placed at the entrance.

Today, the sign and gate are gone, and every year the woods claim a little more of the cemetery’s history.

This is just a small glimpse of the history that surrounds the Triadelphia and Roney’s Point area. I plan on researching future topics about this area and the Roney’s Point Cemetery. In my eyes, the cemetery is important because it tells the story of the sick, the unknown, the poor, those who succumbed to tragedy. Their story is important and it must be told and remembered.

Ryan Stanton is a 2002 graduate of Wheeling Park High School. In 2006, he graduated from West Liberty State College with a bachelor’s degree in history and later earned a master’s degree in social studies education from West Virginia University. For 12 years, Ryan has been a social studies teacher at Wheeling Park High School where he teaches college-level U.S. Government and Politics and the History of Wheeling.

Love the History of Ohio County. So interesting. Dawn Roth, dlroth@comcast.net.

thank you.

Cemeteries are remarkable places that many ignore. I lost my wife, Barbara on Dec 23, 2016 and she was buried up on the hill at Mt Calvary Cemetery. I’ve visited her grave many times since. But, something awesome happened a few weeks ago while I was at the cemetery. It was just after that terrible storm that caused so much damage. My daughter, her husband and I were checking out our family grave plots and decided to just look at other sections. As we drove through the older section, I noticed a monument with the name Burns on it. Burns was my mother’s family name. I had never met my grandparents and, in fact, had never given them much thought. Until now. We stopped and read the writing on the monument and sure enough, they were my grandparents, Sarah & Henry Burns.