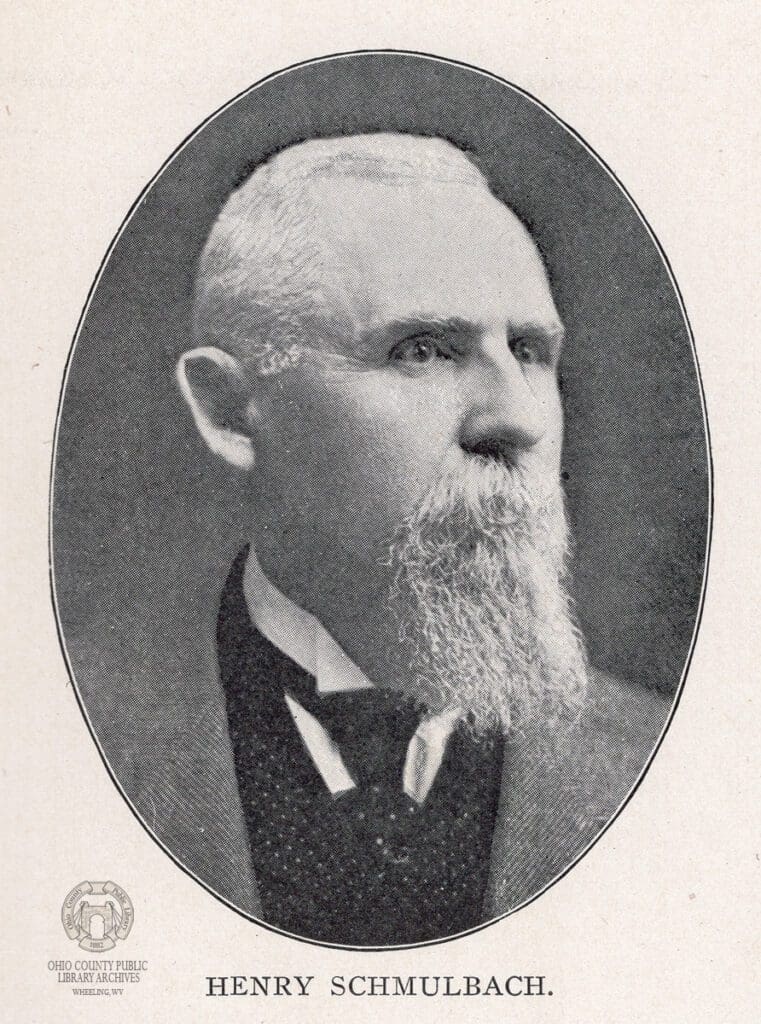

He was a mere 8-year-old child when his parents, Johan and Anna Elizabeth Schmulbach, joined another family to depart Germany for the United States.

The Schmulbachs settled in Wheeling as did thousands of other German immigrants because not only did the region have German-language newspapers and several relevant singing societies, but employment also was in ample supply to hard-working men and, in some cases, male children. Henry Schmulbach was such a young man and at the age of 10 he accepted a cabin boy position on a steamboat offered by an uncle, George Fellers.

Once the Civil War began in early 1861, Schmulbach left the waterway at 17 years old to open a grocery store in the area now recognized as Centre Market. He sold the retail business operation three years later and briefly returned to the steamboat industry, but according to information listed in the Ohio County Public Library archives, it was in 1865 when Schmulbach got his first taste of the alcohol business in the Upper Ohio Valley.

“By all accounts, Henry Schmulbach was a very motivated young man,” said local historian Ryan Stanton, an educator at Wheeling Park High School. “I’ve not found any documents or direct quotes about his thirst for money, but his early work history certainly appears to have something of a start as far as his wish to collect as much wealth as possible.

“Henry must have been a saver in his early years, too, because it’s apparent he jumped from one industry to the other and not as an employee but as an owner,” he explained. “That trend continued, too, with everything he did until he died in 1915. Schmulbach was always in charge, and if he wasn’t when he first got involved with something new, his role always changed very quickly to titles like president and chairman.”

A perfect example of such a movement involved the German Bank of Wheeling. Again, the OCPL’s archived obituary for Schmulbach reveals why the entrepreneur targeted the institution in his late 30s.

“This bank owes its life to Mr. Schmulbach. The bank was incorporated in the late ’40s and grew steadily until 1879. In that year a failure of the tobacco crop, in which much of its resources were invested, caused it to meet severe losses.”

In the very beginning, Schmulbach and bank president Chester D. Hubbard opposed the bank board’s decision to suspend operations, and soon later Schmulbach took over as the bank’s president.

“One of the main focuses for Schmulbach later in his life was the German Bank of Wheeling. Everything I have seen about that stage of his life allows me to believe that the bank was one of the great points of pride of his life,” Stanton reported. “Of course, the German Bank of Wheeling is now known as Wesbanco Bank, so he must have built something that has lasted through the years when many banks have not. I think it speaks to the due diligence that he displays with everything he did both professionally and for recreation. He made sure he did everything the right way.

“By all accounts, I’ve seen, that’s how he went about everything beginning when he was young through his 70 years here,” he said. “I believe his life is the true story of realizing the American dream as it was presented to immigrants at the time he moved to the United States as a child.”

A Brewer’s Death Nail

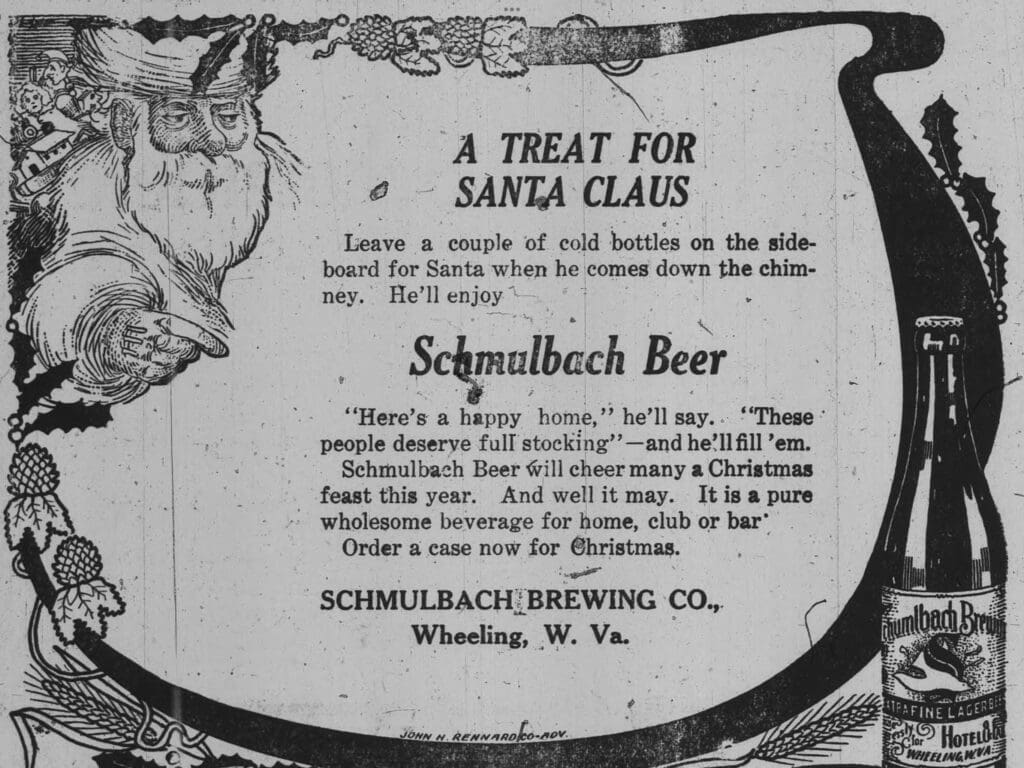

In the 1912 general election, after years of effort by state lawmakers, a majority vote by 92,342 Mountain State residents cast ballots in favor of prohibition, which became state law at midnight on June 30, 1914.

It was not until Dec. 5, 1933, when the 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified and effectively repealed nationwide prohibition, and West Virginia was the 15th state to vote in favor of repeal. Schmulbach, and his brewery, however, already had been dead for nearly 20 years.

“When lawmakers in West Virginia approved prohibition, that had to have broken Schmulbach’s heart because he had worked so hard to establish what he did in the brewing business. At first, his board of directors tried to relocate the brewery to Ohio, but that never materialized, and I believe part of the reason why was because Henry and the others were so well off at that point that they let it go,” Stanton said. “To the employees of the brewery and the employees of all the other connected businesses, it had to be devastating, but for a guy like Schmulbach, he had so much wealth and so many other businesses that he really didn’t need to brew beer anymore.

“But it still had to hurt. It was what he was really known for,” the historian considered. “They had a lager, a porter, and a crown ale that were very, very popular, and they had some seasonal beers as well for certain times of the year. The man loved his heritage and that’s why when the fall rolled around, he brewed and distributed an Oktoberfest beer that was said to be very good,” he said. “Schmulbach was also a master marketing guy, and it was obvious he had a lot of fun with it.”

Of course, Henry Schmulbach succeeded in establishing yet another “first” despite having died following a year of poor health.

“There was a time when a person could take a trolley from downtown Wheeling to Roney’s Point, and when Schmulbach died, they had the funeral up here, and they had special trolley service to get everyone to the service. By all accounts, that service was a very big deal,” Stanton said. “Henry actually had the first funeral procession that was led by automobiles. The very first ever in the Wheeling area.

“Not only was this guy an entrepreneur and the first person to do a lot of different things, but he was a very driven man to set a lot of standards in this area. The Schmulbach Building, which is now known more as the Wheeling-Pittsburgh headquarters, is an example of how he went about it the right way,” he said. “That’s why seeing the mansion the way it is now with so much of it missing and all of the vandalism and graffiti that’s taken place is a pretty sad thing to me.”

The Widow

When Pauline Bertschy Schmulbach passed away several years after her husband’s death, her estate was valued at more than half a million dollars, a figure that would exceed $8 million today.

That estate, however, did not include the family’s property at Roney’s Point because she had sold it to Ohio County for $125,000 in 1917.

“She didn’t want to live there, not even when Henry was alive,” Stanton insisted. “Not only did Henry and Pauline know each other from their church, but she was the hostess at the family funeral parlor. She was a very social lady, so living out in the middle of nowhere like Roney’s Point was back then never appealed to her. She did it, but once she could sell, she did.

“But back then, very soon after the Great Depression hit, Ohio County utilized the land as the county poor farm. The men of the county would go there and work the farm so they could earn some of the food they produced there, and they also earned a few bucks each day that they were able to take home to help with their families.”

Some of the men, Stanton said, would live on the property, too, and the county established the County Farm Cemetery for the interments of those who passed away during those years. The graveyard later was utilized for the patients who passed away at the hospital, and those who simply wished to use the yard as their final resting place.

Most of the graves today, however, are unmarked, and the gas and oil industries as well as flooding have left the cemetery completely unmarked.

“That’s just an example of everything else that has happened to the Schmulbach property at Roney’s Point,” Stanton said with disappointment. “His Chapline Street home has been preserved, and it’s now in a protected block with other beautiful Victorian houses, and the brewery building still stands, too, and the Schmulbach Building is pretty much known as the Wheeling-Pitt building now because the steel company had several floors of it for its headquarters for a lot of years.

“But with all my research on Henry Schmulbach, I have always had the impression that it was the Roney’s Point property he was most proud of because it was where he could take all of his hobbies and have fun with them,” the historian added. “But then it was all allowed to just rot, so I guess, it’s gone the same way the American dream has through the years.”

(Photography by Michael Novotney)

Were there any beer recipes that survived from back in the days of the brewery?

Thanks for Part 2. My grandparents lived and worked there for some time during the 30s when it was the “County Poor Farm”. I’ve always been confused with the timeline as everyone has always referred to it as the “insane asylum” for TB patients.

I got arrested for underage drinking up there 30+ years ago, (ironically by said grandparents neighbor), so I never went back to get the full story. 😆

Comments are closed.