It was about now, usually – a couple of months after that natural amphitheater in East Ohio had fallen silent – when Kelly Tucker would sit down with herself and assess whether or not the goals were met.

She didn’t use a checklist because, well, what would that have looked like anyway? Was the hillside full of fans having fun? Check! Was the country music loud enough for all to hear? Check! Were there enough porta-potties? Check! Did Neal McCoy conjure Beetlejuice? Check!

And were the hand-crafted casket coolers full of beer? Well, of course, there were.

The measuring sticks were the measuring sticks, after all, and for decades they were the only ones that factored into the “next year” decisions because, at least for the first three decades, making money was automatic as long as there were 30,000-40,000 fans filling that East Ohio hillside.

“There were years that were better than others,” recalled Tucker, who was named the general manager of the former country music festival. “But then it didn’t matter how many people came to the shows because of how much we had to pay the performers. Those fees exploded once all music went digital.

“I think the 1990s is when country music went mainstream. No longer was it that other music but instead, to a lot of people, it had become the music,” Tucker said. “I remember that a very young Garth Brooks was at Jamboree in the Hills (in 1990), and at that point, no one knew how big Garth would become. But at Jamboree in the Hills, I think he gave the fans an idea because that was one of the best shows I think I saw there.”

Kyle Knox now is in his second stint with the Greater Wheeling Sports and Entertainment Authority, the municipal entity in Wheeling that operates the Capitol Theatre and Wesbanco Arena. This time around, Knox is the marketing manager for the two venues, but during his initial tenure, he was in operations and was first hired by JITH as a member of the production staff in 2012.

He views Garth Brooks as the biggest game changer in the history of the country music industry.

“I look at country music this way – pre-Garth and post-Garth – and I had a chance to talk with Garth Brooks about his Jamboree in the Hills performance back then,” Knox revealed. “He claims to remember being there and it was a pretty unique event at the time, so I am sure he does.

“After Garth came out, everything in the country music industry shifted,” he said. “It was still about the music, but it also became about the show because, without even trying, Garth was a tremendous performer who put on one heck of a show.”

Tucker completely agrees.

“When the crossover took place with country and pop, we saw our Jamboree in the Hills crowd grow larger and larger,” Tucker reported. “There was paving and other capital improvements on the property, the new stage was built in 2005, and Jamboree in the Hills expanded to a four-day festival with a pre-show concert on Wednesday. At that time, I think we all believed it would go on forever because it seemed as if it was getting more and more popular each year.

“When I saw how the music industry was changing as far as how the artists were making their money, it became obvious their tours became the money maker instead of record and CD sales, and that started to cause problems,” she recalled. “If I have to be honest, I never thought (Jamboree in the Hills) would ever go away. I thought there might be changes. But I never thought it would go completely away.”

It Was Called the Super Bowl

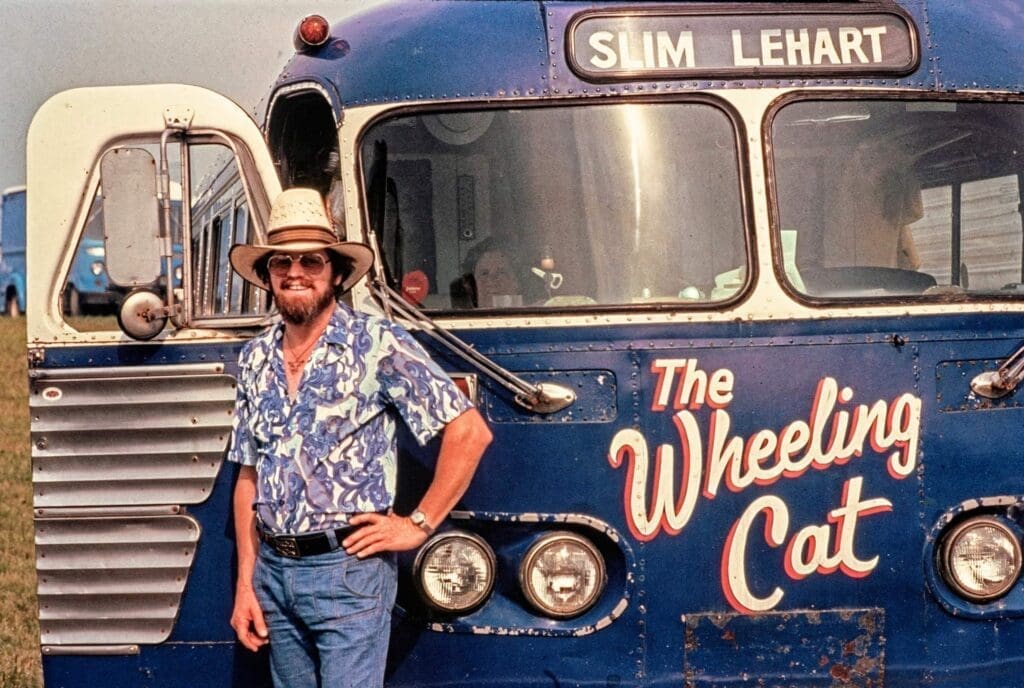

Brush Run Park was the first home for Jamboree in the Hills, and initially, it was a two-day festival created because of the long-time success of Jamboree U.S.A. at the Capitol Theatre. Each Saturday in downtown Wheeling, Main Street was lined with tour bus after tour bus, and thousands of fans filled hotels throughout the region.

There were two sold-out shows each weekend, and the then-Capitol Music Hall was second only to the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville when it came to venue ranking for country music.

“My mom always told me that Jamboree in the Hills was a spin-off of Jamboree USA because of how popular those Saturday nights were in downtown Wheeling. She said they thought if one day could be that popular that a two-day festival would be a hit, but no one imagined what took place,” Tucker said. “Back then, Jamboree in the Hills featured the biggest names in country music, and they went up on stage one after another.

“Most of the stories about back then that I’ve heard have all been about how wild it was, and I’m pretty sure that’s why my mother didn’t allow me to go until I was 17 years old,” she recalled. “I know it got a little tamer when it moved from the airport site to the second site that was right along U.S. 40, but before then, it was known as the Woodstock of country music for a lot of reasons. That made me want to go even more, but my mother had set down the law and she wasn’t budging until 1993. That’s when Little Texas came, and she let me go.”

Knox has heard tale after tale.

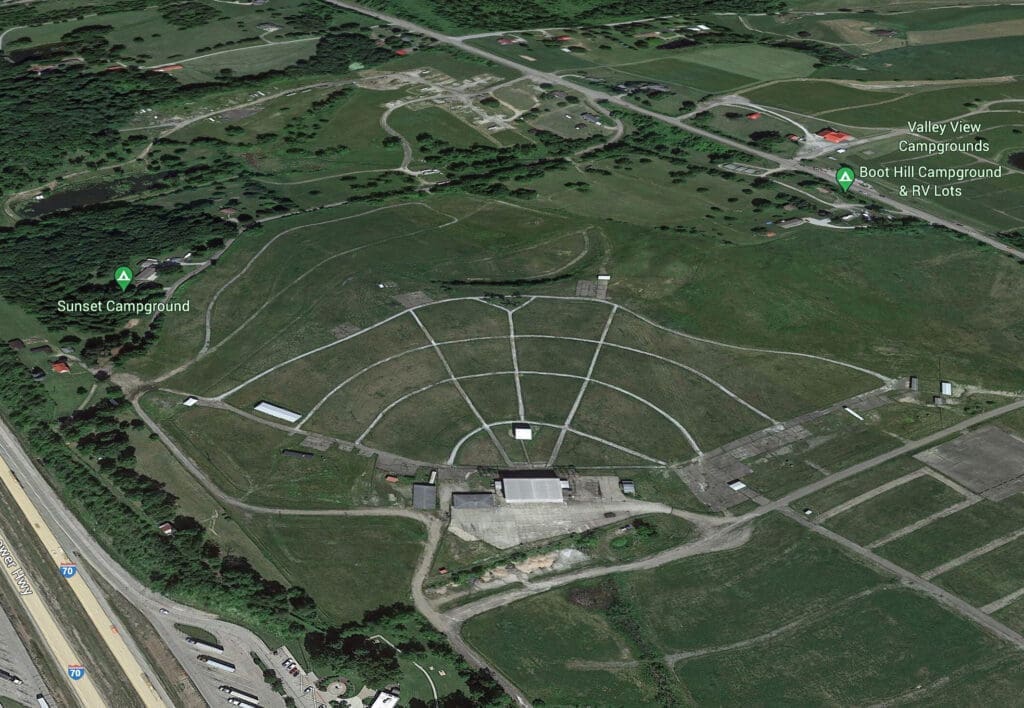

“And I’ve been told that during the early years, no one really knew what kind of infrastructure was going to be needed to pull off what they wanted to do, so I’m sure there was a lot of learning the very first year that made it better and better. People need restrooms, they need water, and they need food, but what else? They found out,” he said. “And I know our area has a lot of great festivals, but when Jamboree in the Hills moved to the second site in 1991, I doubt many people realized that it was like building a city in the middle of nowhere every single summer.

“That’s why it wasn’t just a festival. It was a city with a festival in the middle of it and it was a huge undertaking all the way up until the end,” Knox explained. “It took a lot of people and their hard work to pull that off.”

And the fans attended in droves.

“Jamboree in the Hills, at the first site and at the second site, was the place to be. It was the event and if you weren’t there, people wondered what was wrong with you. Everyone was in Belmont County, Ohio because Jamboree in the Hills was the hottest ticket there was, and that was true for a lot of years.

“I really never experienced Jamboree in the Hills like all my other friends did, though. I was always working. I started out front at Will Call and the ticket lines at the entrance, and then, of course, my role expanded through the years. But, even though I worked, it’s still hard to explain to people what it was like and what it meant to people,” Tucker said. “Jamboree in the Hills was so important to our Ohio Valley community, that’s for sure.”

The New Definition of ‘Hiatus’

First, there was “Jambo Country.”

The re-branding was introduced in 2016, and it included the announced end of the festival’s “Bring-Your-Own-Booze” policy, and the changes were met with fiery and rage. Tucker’s life was threatened multiple times and boycotts were being organized,

Live Nation quickly dumped the idea.

“The reaction from the fans was fierce and it was angry,” Tucker said. “I knew people weren’t going to be happy, and that’s what I told the people I worked with at the time. But the reaction even surprised me. It was scary.”

The four-day show continued for two more years with cheaper up-and-comers all day, household-name headliners closing each show, and those coolers of beer continued rolling through every gate.

“I grew up a massive fan of Jamboree in the Hills and I couldn’t wait to get there,” Knox admitted. “When I was a kid, I used to camp out on the floor at home and watch every TV broadcast from the Jamboree. I watched every second and I grew as a musician. I wanted to be on that stage, and then I got to go and be a part of it. That was a dream come true.

“But then in November after that last show (in 2018), the company came out with something about a hiatus, but that’s not what it was. Not at all,” he said. “It was the end no one wanted to come.”

Tucker knew, too.

“We tried everything we could think of, but the industry shifted, and the bottom line was the bottom line,” she said. “For 40 years, it was magic.

“I knew when the shows ended on those Sundays, there was nothing that ever gave me that kind of sense of accomplishment. No matter what my job was before I became the general manager, I just felt very proud to have been a part of something so amazing,” Tucker added. “It became my baby, and then my baby was taken away from me.”