(Publisher’s Note: Wheeling’s history is what it is, and that history does include the existence of organized crime. Books have been written and magazines series published about mob ringleaders “Big Bill” Lias and Paul “No Legs” Hankish, and most of the illegal activity left most people alone. That, however, was not the case one winter day in Warwood 60 years ago.)

Things were different around here back then.

A new, average car was under $5,000 each, and a gallon of gas was 30 cents. The price of a nice, new home was under $21,000, and there were under 200 million United States citizens.

Oh, yeah, and organized crime was prevalent, and local law enforcement, most of the time, tolerated it. There were back-room poker games, bets in billiard halls, bootlegging, spot sheets and bookies, stolen goods, and prostitution. The mob operated not only in the city of Wheeling but throughout the Upper Ohio Valley, and it was not uncommon for deals to be made between different corrupt outfits within the region.

Since there was not a true connection to an Italian family, the organization “Big Bill” Lias operated was known as a “mob,” a collection of criminals who perpetrated profitable operations permitted by the boss. And the mob policed itself, too, and to this day many believe the explosion that occurred in Warwood nearly 60 years ago still serves as an example of such practice.

The portions of this article that are in italics are parts of the narrative from the police reports filed by investigators the day of the bombing and from several days later. The file was acquired from the City of Wheeling’s legal department.

“At 10:25 a.m. this date (Jan. 17, 1964), radio operator Alfred Howard received a phone call from Bill Linton, 4th and Warwood Avenue. Mr. Linton told Howard that a car had been blown up down on 4th and Richland Avenue and a man was in it. Car #5, 10, 11, and (Louis) Kulpa with Lt. Stutz were all dispatched to the scene.

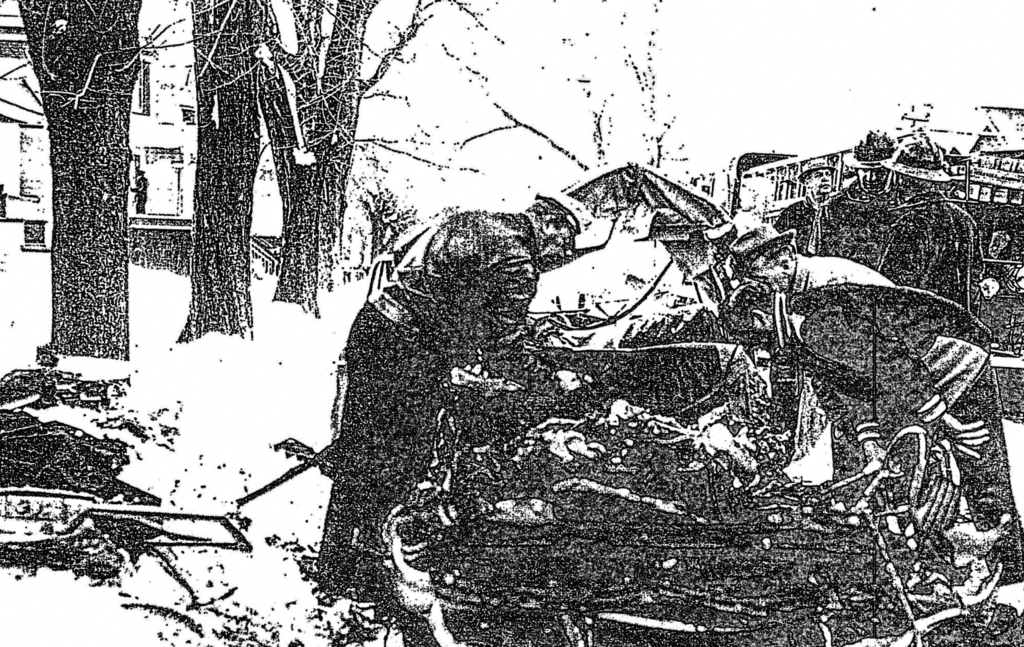

“Car was a 1964 Studebaker, 4 door sedan, tan in color, bearing W.Va. dealer plates DUC 5 609 which is issued to The Auto Ranch, North River Road, Wheeling. The car was in front of 336 Richland Avenue, which is the home of Paul Hankish. Mr. Hankish was in the car at the time of the explosion. On our arrival at the scene, the fire department was attempting to remove Mr. Hankish from the front seat of the car. He was still conscious at the time.

“The car apparently was rocked by a terrific explosion. Both front doors were blown off the car, the entire front of the car, which includes the windshield and firewall, was blown off from the frame. The hood, fenders on the front, the grille, radiator, were off the car and scattered about the area. The yard across the street from the car at 339 Richland Avenue contained two large pieces which had been parts of the fenders; this is about 150 feet from the place where the explosion occurred.

“Other parts of the car were found all over the street. The right front fender was found in the back yard of the house at 408 Richland Avenue. It apparently had blown over the top of the houses.”

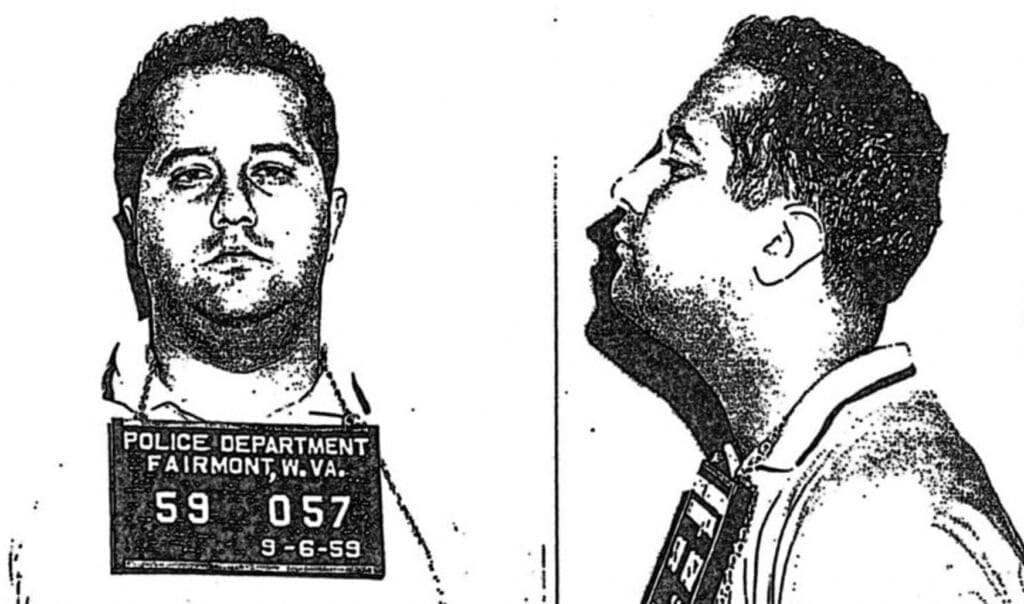

The ‘No Legs’ Nickname

It was a snowy morning, according to the police report, and Hankish didn’t own the car. He was on probation after serving prison time for involvement in a stolen goods operation but resided along Richland Avenue in Warwood with his wife at the time the assassination attempt took place. Hankish was an under-the-table hustler who had made a deal with a local dealership, but the details of the agreement remain unknown to this day.

So do the reasons why many believe Hankish ruffled the feathers of the legendary Lias, the original kingpin of organized crime in the Wheeling area. The victim did mutter something to first responders that, according to investigating officers, implicated Lias.

In the process of talking to Harold Bauers, he stated the following: “When he ran over to the car to what had happened he seen Hankish in the front seat; he was conscious and said the words, ‘That f**king Bill Lias.’ Bauers then ran to call an ambulance.”

Later the same day, Wheeling officers Prezkop and Millard spoke to Hankish, and he again blamed Lias.

“He said, ‘I’ll never change. F**k that fat pig.’ Millard asked who he meant, and Hankish said Lias. When asked if it could have been anyone else from up the river around Youngstown or that area, he said, ‘No. I get along with everybody but him.’

“Hankish at this time was still in pain but was coherent, and his condition was good.”

A Warwood resident, Harold Bauers of 346 Hazlett Ave., informed police he witnessed the explosion. The report states Bauers noticed Hankish walking down his front steps and enter the Studabaker, and then he saw – and felt – the bombing.

Seven homes, the police reports included, were damaged by the explosion, and debris was discovered all over the neighborhood. John Niebur of 340 Richland Ave., the report states, told officers he found a piece of the Studebaker’s hood on his house roof and other fragments in nearby trees.

Hankish survived, but he lost both his legs.

The Inevitable Q&A

Accusations are one thing, but the proof is in the pudding.

According to the reports, officers spoke with “Big Bill’s” known associates, friends, and his wife, Patricia, and there was a consistent answer.

“He never talked about his work.”

But some saw what they thought they saw. Det. C. Gilson filed this report that day after the murder attempt:

“At 9:00 a.m. this date (January 18) I was informed to see an Ann Thalman at 339 Richland Avenue by James Harkins in regard to a woman that said she had seen two men “fooling around (with) a neighbor’s car” which was similar to the one bombed.

“At 9:15 a.m., I talked to Ann Thalman, and she said to see her sister, Josephine Bauman, who informed me that the woman I should see was Ann Schmelick of 300 Richland Avenue.

At 9:45 a.m. I talked to Ann Schmelick and her husband. The only thing said by Ann Schmelick about the bombing was that she owned a 1964 Studebaker, 2 door, but not the same color as the one bombed. When she learned that a “Stud” had exploded, she thought that it was the product and did not know that it was bombed. She said she was afraid to start her car thinking that it might blow up until she was told that the other car was bombed. At no time did she state that she saw two men ever fooling around her car or anyone’s car.”

Anonymous calls constantly were received by hospital staff members from people checking on Hankish’s health, and some, according to the reports, simply and quickly asked if the 32-year-old was alive or dead. The hospital’s staff members, according to the case file, never revealed Hankish was a patient let alone his official condition.

There were callers who offered anonymous tips to the police, but there was plenty of silence, too. “Big Bill,” though, did meet with investigators.

“And then on Jan. 21, 1964, with Hankish spending his fourth day hospitalized, Wheeling police officers Lt. Thomas and Sgt. Noll filed their report about their conversation with Bill Lias. At 10 p.m., they traveled to his residence on 15th St. in East Wheeling, and they asked him why his name might have been mentioned by Hankish.

“He told us that he and Hankish have not seen each other for approximately three years; this was before Hankish went to the penitentiary. He stated that he knew that Hankish was saying derogatory statements about him, but it made no difference to him. He said that if remarks bothered him, he would have been bothered his whole life.”

Eras End

It has been reported that Hankish hired mafia hitman Raymond Freda to kill Lias later in 1964, but the federal agents found out and let “No Legs” know. “Big Bill” passed away on June 1, 1970, at the age of 69.

He, nor anyone else, was ever charged with attempted murder stemming from the Richland Avenue bombing.

Twenty years later, though, the federal government charged Hankish with 218 counts, and he was sentenced to 33.5 years in federal prison and fined $72,500 in October 1990.

The kingpin pled guilty to one count of violating RICO laws, three counts of using the telephone to gamble, three counts involving cocaine distribution, and two counts of filing false income taxes, but could have received as many as 77 years and a $1 million fine.

Paul Nathaniel Hankish passed away on May 11, 1998, at the age of 66. He was still in federal custody at the time of his death.